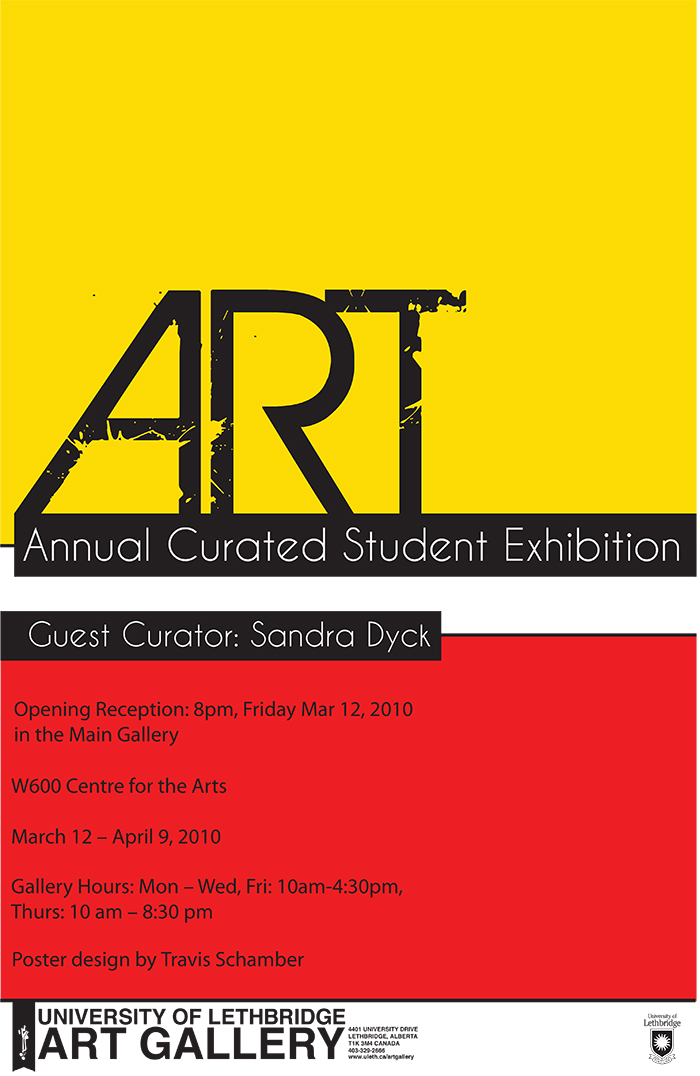

The Object of My Attention: Annual Curated Student Exhibition 2010

Main Gallery

Guest curator: Sandra Dyck

Selected artwork from Senior and Advanced Studio Students.

The University of Lethbridge Art Gallery provides an exceptional opportunity for the professional development of Art Studio majors as they near completion of their degree. The Annual Curated Student Exhibition has recently been revised to give students realistic experience with the process of applying for exhibitions and receiving feedback from an established curator. The exhibition is only open to senior art majors in order to focus attention on those with the goal of becoming professional artists. In applying for this exhibition, the students follow the same process and standards for documenting, describing and proposing their art work as they will when applying to public art galleries and artist run-centres or for grants. Staff from the Art Gallery provide advice on preparing the proposals and share insights into what curators look for when deciding to book a studio visit and choose art work for an exhibition.

An established curator from outside of Lethbridge is invited to create the exhibition. The curator views the proposals and selects a short-list of students for follow-up meetings during a visit to Lethbridge. From these studio visits, the curator makes the final selection and works with the Art Gallery staff to lay-out and install the exhibition.

The Annual Curated Student Exhibition provides a showcase of excellent work by Art Studio majors in that year and gives the students a valuable achievement to list on their résumés. As well, the students who are not selected receive feedback on their proposals and can learn how to improve as they prepare to begin their careers.

Visit the Faculty of Fine Arts.

Artists (click image to enlarge)

Yan Luo

Yan LuoA Clear and Present Danger, wax casts of hand sanitizers, 2009

Self Portrait, wood, glass, lens, fluorescent lights, 2010

Kari Martinez

Kari MartinezUntitled, fabric on cardboard, 2010

Fabric Cube 1, fabric and batting, 2010

Fabric Cube 2, fabric and batting, 2010

Fat Cube, fabric and batting, 2010

Sara McKarney

Sara McKarneyMy Parents’ Kitchen Table, fingernail scratch marks and ink on thermal fax paper, 2010

Arianna Richardson

Arianna RichardsonBric-à-Brac Husbandry, plaster, glitter, sugar, 2010

Bric-à-Brac Husbandry, plaster, glitter, sugar, 2010

Curatorial Statement

“The creative mind,” Carl Jung said, “plays with the objects it loves.” This exhibition is about objects. It presents things that artists have made anew, recycled, copied, re-examined, modified and recontextualized. Their “love” of objects – their sustained attention to them – makes us look at the stuff of life in fresh ways and from different angles.

Kari Martinez and Jason Jessen, for example, re-purpose familiar materials – quilting fabrics and pressure-treated lumber – to new, Minimalist, ends. Brenna Crabtree takes the most banal of objects, the plastic bread clip, and, in a classic Pop art gesture, makes it monumental.

Yan Luo and Arianna Richardson rework ordinary things: Luo the now-ubiquitous dispenser of hand sanitizer and Richardson some thrift-store tchotchkes. By casting in wax (Luo) and plaster (Richardson) multiple copies that are variously embellished and installed in orderly arrays, the artists effect fundamental shifts in the contexts for their reception.

Jarrett Duncan and Monique Bedard sit in front of the camera, objectifying themselves in videos at once intimate and intense. Bedard’s enigmatic photographs of the exterior world shot from a camera held inside her mouth revisit traditional concepts of self-portraiture. Yan Luo’s portable camera obscura offers up a constructed image — of a Bauhaus-style chair – that is continually modified by the lens’s capture of real-time activity occurring outside the crate’s confines.

Sara McKarney uses her fingernails and scroll-like sheets of fragile thermal fax paper to make a frottage drawing that records the surface of her parents’ kitchen table – an object that will change over time, even as the drawing fades and deteriorates. In accordion books made from her folded and bound monotypes, Francine Desjardins seeks to give form to the inexpressible: the sound (and her experience) of music. Kazumi Marthiensen’s kimono is motivated by a similar, but more specific, impulse to make experience visible: the helicopters and planes adorning her garment manifest the people of Okinawa’s resistance to the presence of an American air force on their island.

Julia Marjerrison draws in a spontaneous way, using watercolour pens and water to create quirky pairs of forms that play on the tension between abstraction and representation. Our persistent attempts to “identify” these imagined shapes – to associate them with things in the real world – demonstrate the very power and presence of objects.

– Sandra Dyck

Guest Curator

About the Artists

Monique Bedard

We all know we can see with our eyes but can we see with our mouths? No. However we can perceive with out mouths. My previous work explored portraiture and the human figure. Currently, I am examining the symbolic within the human figure. Through photography, bookmarking, video, and video stills, I am addressing the binary issue of representation, the psychological dimensions of the body as revealed through the dualities of intimate/public and interior/exterior.

In my early series featuring mouths, the oral perspective consisted of a void; an exterior representation. Whereas in my work titled “Mouthpiece”, the perspective changed. I placed a miniature spy camera inside my mouth and the negative space became filled with the exterior surroundings. As my mouth makes different shapes, the concepts of intimacy, the private, interior and exterior exist in an abstract way. I am very interested in the negative space of the mouth and its ability to form relationships between the inside and the outside. My recent work shows that an oral perspective is possible through a sensory transportation from perceiving with our eyes to perceiving with our mouths.

Brenna Crabtree

I am interested in learning new things about ordinary objects. Kwik-Lok Closures (also known as bread clips) are fascinating because they are mass-produced, are characteristically flat and grip-able, they function strictly as bag closures, and are manufactured to be disposable. I am currently constructing three enlarged Closures made of plywood that are 5′ by 4′ in order to enhance the physical presence of these objects, and to explore how the identities of the large replicas differ from the original object in terms of their ability to function, their importance and their relationship to the human body. I have experimented with different installation arrangements of two plywood closures that are currently in progress and have included documentation of the arraignments with this application. The completed project will consist of three plywood Closures, each 5′ by 4′ and painted in a colour that is traditional of original Kwik-Lok Closures.

Francine Desjardins

This work involves printmaking as a medium to express the shape of music. As I listen to a specific selection, I transfer what I see on the inked surface using a subtractive method. Ir emote ink to express the shapes I see. For me, sounds have explicit colours; music has detailed shapes. The pitch of the operatic voice as musical instrument and the plasticity of oil based, intaglio ink creates harmony for my monotype. I decode my auditory/sight experience into my artwork. For example, as sounds change, the colours I see change. Int his work, the operatic voices are transposed to the printmaking surface as shapes.

Jason Jessen

My work started out exploring the emotions that were tied to personal experiences that I had encountered over the last few years which were to me, traumatic and unfortunate. I wanted to express these inner emotions that were so deeply infesting my heart and mind in hopes of finding relief from its aching burden.

My works entail the portrayal of the body in extreme Caravaggio settings and the use of objects with great metaphorical significance which creates a dialog of emotional distress or confusion. I have experience in painting and sculpture which have greatly influenced the outcome of my most recent use of media which is photography, for I create my compositions comparable to how I paint, as I gather various elements and compile them into one body that is often staged and/or has a narrative which provide further symbolic intrigue and sublime aesthetic qualities.

I have created work that is entangled with the issue of identity and how its central figure is based around the question” who am I?” which topic has derived due to my unique and complex up bringing. I am a hybrid of Cree and Yugoslavian but was adopted at an early age into a family whose roots are Danish and Scottish who knew very little, if anything about my aboriginal culture and I have a great void that hinders the knowledge of my life’s history which is a mystery to me and has been a contributor to my disconnected feelings in society and the misconceptions of my identity. My most recent works deliberately addresses personal and national identity, which are tied to political and social issues associated with the Group of Seven and their historical events, which have influenced me in a positive and negative manner, especially on the notion of Canadian National Identity. I am Canadian and Aboriginal, I am raised to live like a Canadian but my skin is dark like an aboriginal and the battle of what I should be as opposed to what I am is stirring with in me unbridled, for I see this world through two pairs of eyes and I live in two worlds, the living and the dead or the stereotyped and the envied and I am unable to escape my outer appearance due to my inner voice.

Yan Luo

I propose to install a functioning projection system modeled after a camera obscura inside the Art Gallery (2’x4’x4’, see fig. 4). Instead of projecting an image of the outside into a camera–as does occur in a typical camera–I want to replace the outside with a constructed scene on the inside of the device, to change the relationship between the viewer and the subject to be looked at into a conscious awareness between each other. I suggest that this awareness was once absent without the recognition of the pinhole and the space the viewer and the subject occupy. In short, my device, a sculpture, is a projector that invites people to enter. Viewers may observe an image being projected from my projecting camera obscura onto a “screen”.

Johathan Crary wrote in his essay The Camera Obscura and Its Subject that, “Movement and time could be seen and experienced, but never represented”p34 to emphasize the difference between the camera which reproduces and the Camera Obscura requires actual participation.

In my piece, two rooms are constructed to host the object; in one, I place a chair, in the other, I invite the viewer. One is pitch black, the other is filled with light. The chair is made by myself mounted upside down in the light room. A pinhole is drilled through the dividing wall to allow light rays to project onto a screen in the dark room. The two rooms are connected this way.

I see the chair as the extension of my body. In today’s world, an individual is no longer limited to his physical body but rather, she or he acts as a part of a whole; the whole for me is the society a living body functions in. The disappearing of the self is a potential danger accelerated by Capitalism.

Here the projection is not merely a chair, but is a projection of me; a self portrait of sorts. At the same time, the viewer is sitting on an identical chair and looks into an identical space, a space absent of a human figure. It’s possible then that one may realize that it is not a projection one is looking at, but rather a reflection.

This work brings the history of photography, through the apparatus of a camera obscura, a device designed to allow a viewer to perceive the wonders of nature within a dark room into an gallery. The idea of a dark room is later applied to theatre to create the separation between the audience and the characters. In Laura Mulvey’s essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, she explains how the screen allows the male audience to project them onto the male protagonist and finally achieve the goal of possess the female protagonist. The idea of projection intrigues me because it is only appearance, illusion which barely expresses any human experiences but we are trapped in it.

The beauty of a pinhole, an aperture, is that it preserves the object/light projection relationship. The appearance (the light reflection returns to our eyes) is then one aspect of the characteristics of the object but never dominates or overtakes. What is real then remains at an almost mystical level and is not rationalized.

Julia Marjerrison

For me, making art is cathartic. It enables me to achieve a meditative state and to distress from daily life by focusing on nothing but putting brush to page. have been exploring ways to express the unconscious through automatic painting, including painting shapes with liquid mediums on a variety of papers. It is important for me that the shapes emerge somewhat haphazardly, creating a push and pull between the influence I have on the shape and the accident of colors mixing and bleeding. I take satisfaction in watching the colors leak over the paper surface , merging form and background while following paths created by the water. The final product is whimsical, with some shapes begging to be named a specific thing.

Examining the conversations between various shapes reveals how we read abstract forms. The viewer often files the individl1al shapes into categories, at times seeing the entire work as a representation of life itself. Since categorizing always happens through the lens of culture and experience, acknowledging this invites us to be aware of, and to question, our process of interpretation.

Kazumi Marthiensen

Growing up in Okinawa, Japan, I experienced the constant presence of the American military, which the Okinawan people have been against from the start. For my current work, I focused on the event that is presently being discussed in the media regarding the fate of an American military base in Okinawa. The American and Japanese governments are holding talks to decide whether to relocate the base on the island or move it off the island. These talks have been going on for years with the preservation of pol itical and economic ties being valued over the strong feelings of the Okinawan people, which are rarely heard. When the issue is in the media, people pay more attention, but soon forget.

American military bases have been present in Okinawa since the signing of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security i n 1960. As result, American military aircraft are constantly flying over the island, which poses a safety concern for the Okinawan people and is a sym bol of the military presence. The American military has become part of everyday life in Okinawa.

The presence of American military personnel is also revealed through instances of abuse toward women. Sim ilar to the relocation issue, when sexual abuse toward Okinawan women by American military personnel is pu blicized, many people become aware of the incidents; however, the issue is forgotten as time passes even though the situation still exists.

To create the work, I looked into Miriam Schapiro’s Kimono, Barbara Todd’s Security Blanket: 57 Missiles, and various rugs done by Afghan weavers during the Russian invasion in 1979.

Kari Martinez

In a dark room lying in bed plans are made to create……

Slipping from ordinary to extraordinary, sedentary to contemporary, immobile to performative ……

My studio practice encompasses the transformation of everyday objects by altering their signature meanings. Through careful examination of self and relationships to others I have discovered connections to the historical act of woman’s craft, quilting and domestic life. Learning domestic stitching and quilt construction I have related to generations of past women; some known and some unknown. I enjoy thrift store shopping and the discovery of materials, patterns, fabrics, collages and artifacts.

Reflecting striking memories or bold history something seems oddly familiar …. Answers await in the light of darkness …….

I am currently exploring the transformation and recreation of house hold items, quilts and threads with slight manipulations and deconstructions. These works are influenced by minimalist artists such as Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt and Michelangelo Pistoletto . The mixing of masculine shapes and strong lines intertwined with emotionally charged fabrics provokes a unique dialog between object and material. I am focusing on simple elements such as line, space, volume and texture. Through use of these elements my work

generates new connotations and constructs new connections between the handmade craft and the modernist static form.

Contemplation can start and end while quietly lying in bed …….. Comfort and familiarity aspires in memory and emotions …..

Creating the conceptual can be achieved when old fuses with new and the new sequesters symbology.

Sara McKarney

My work is an exploration of unappreciated objects and surfaces, such as worn-out shoes, damaged tables and cracked concrete floors. Physical abrasions found on these objects are records of a rich history that I want to bring to light. The subjects I record are of individual or

group histories. Worn-out shoes present the characteristics of an individual’s movement that deteriorate the fabrics and rubber in a unique way. A work table that is cut into and spotted with paint displays multiple people’s use. Both of these and similar items are an accumulation of insignificant events which I want to explore and celebrate, acknowledge the passing of time.

My process is a physical exploration of these objects through drawing. I approach this through both aggressive gestural drawings and a controlled detail oriented method. The gestural in the exploration of old shoes are able to focus in on the worn out areas. I am able document the tables and cracked floors through scratching over heat sensitive paper with my fingernails which presents the damaged areas. To bring those areas further to the surface, I highlight them with ink. These methods allow me to explore and fully appreciate the histories recorded into the objects.

With the use of my body to translate the past, the produced image is an abstraction of the original object. This connects me to what has occurred by implanting myself into this timeline. The process of documenting through the scratching also has an effect on my body. The wearing down of my fingernails strengthens the connection I has in the process of the translation, while the loss and addition of information that occurs makes them unique images on their own. Both my techniques adow me to present overlooked areas or cast away objects as the rich histories.

Arianna Richardson

The Readymade is an inherently depersonal ized piece of art; the artist is not the creator and the object itself is reproduced by the thousands. Common, domestic decorations are the same in that they are superfluous, mechanically reproduced and readily available. In our society, they speak more of fashion than of function ; usually employed for a short period of time until replaced with another more desirable object. Despite

their very disposable nature, ornaments are always carefully chosen , collected and placed in order to assert a particular identity [both for people and places], giving them a strange quasi-uniqueness. They provide identity while simultaneously lacking one and they speak of permanence and particularity when they are so easily and constantly replaced.

In my work, Ifocus on exploring and exploiting this strange place that the collection of ornamentation occupies in our society. It is important that the materials I use are amassed from secondhand sources, that they are abandoned and originate in mass production. Initially they are chosen on an intuitive level for their attractive, formal qualities, ensuring that the culture of collecting and decorating remains intact. Then I can objectively analyze the associations that they have and give them a new existence that is independent of their previous use.

In the photographic series “Ornament and Obscurity”, the decorations are applied to my body in the form of an absurd and impractical costume. Their original purpose is denied as they are not providing an identity to their user and they are made strange by the fact that they are out of context and unrecogn izable . The formal qualities of the

photographs themselves speak of intuition and indistinguishable emotions so as to keep in line with the method in which they were collected. This also furthers the removal of their identity.

In my sculptural practice I repeatedly reproduce and recreate these objects without the industrial mechanisms which with they were initially produced. This craft-related production is the antithesis to mechanization: it reintroduces the artist’s individual hand to an impersonal Readymade. An absurdity is seen in the austere and minimal gestures : the individuality of the object is almost denied by the fact that it is not outwardly exerting its personality ; the artist has created something with extreme care but has not made this immediately apparent. The objects are estranged and the viewer must confront their reaction to them with questioning: Where have I seen this before?

What was its relationship to me then and what is it now?

About the Curator

Sandra Dyck is curator at the Carleton University Art Gallery in Ottawa. She has curated 40 and coordinated 150 exhibitions, and published 16 catalogues. Her recent essay, A Pilgrim’s Progress: The Life and Art of Gerald Trottier, was recognized with a 2009 Curatorial Writing Award from the Ontario Association of Art Galleries. She contributed essays to Around and About Marius Barbeau: Modelling Twentieth-Century Culture, published by the Canadian Museum of Civilization in 2008, and Edwin Holgate, published by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2005.

Sandra Dyck is curator at the Carleton University Art Gallery in Ottawa. She has curated 40 and coordinated 150 exhibitions, and published 16 catalogues. Her recent essay, A Pilgrim’s Progress: The Life and Art of Gerald Trottier, was recognized with a 2009 Curatorial Writing Award from the Ontario Association of Art Galleries. She contributed essays to Around and About Marius Barbeau: Modelling Twentieth-Century Culture, published by the Canadian Museum of Civilization in 2008, and Edwin Holgate, published by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 2005.

19 thoughts on “The Object of My Attention: Annual Curated Student Exhibition 2010

March 12 – April 9, 2010

Main Gallery | Centre for the Arts | W600”