Absence or Presence

Absence or Presence

January 24 – March 7, 2003

Main Gallery

Curator: Curtis Joseph Collins

“The presence or absence of a recognizable image has no more to do with the value in painting or sculpture than the presence or absence of a libretto has to do with the value of music.”

– Clement Greenberg, “Abstract, Representational, and so forth,” Art and Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961) p.133.

This exhibition from the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery’s permanent collection focuses on abstract painting in Canada from the 1950s to the 1990s. The absence or presence of discernible subjects in such a body of work represents a key fluctuation in modernism’s cyclical nature. Each artist’s manipulation of colour, texture, form, and space appear as immediate solutions to the problems of image making, when in fact they are part of an aesthetic tradition that has existed for over a hundred years in Western Europe and North America.

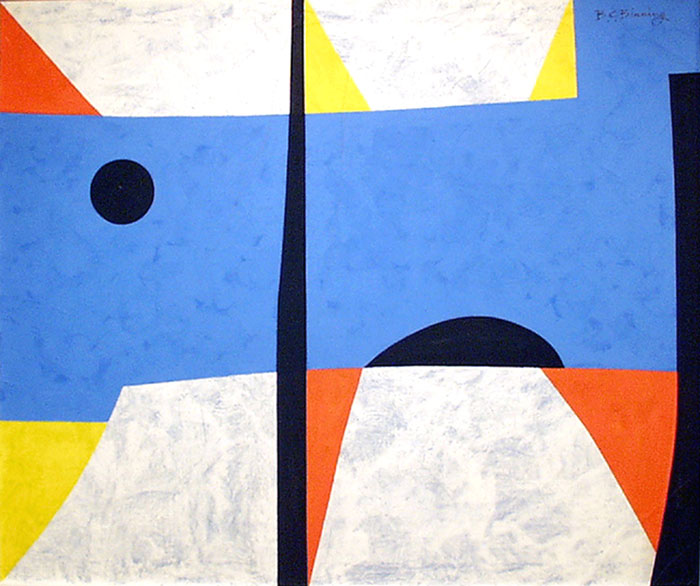

The show’s signature work by B.C. Binning entitled Black Island (top of this page) is indicative of the central position abstract art had gained in urban Canadian cultural milieus by 1960. While the Vancouver-based painter’s reconstruction of a seascape is undoubtedly a summarized image in the modernist sense, it does not completely depart from the recognizable. Such an approach by this artist speaks to the influence that the mid twentieth-century British figurative sculptor Henry Moorehad over him. Ultimately Binning maintains the ancient Western tradition of treating the canvas as a window onto a receding natural space, which enables viewers to share a common associative experience.

Harold Town’s 1974 oil on linen Snap #78 (see Image 1 above) provides a fitting contrast to Binning’s piece for it completely releases easel painting from its primordial link to an observable reality, and evokes an incredible surface play of colour and line. The image now becomes a screen rather than a window, that has been produced by loading lengths of string with unmixed oil paints and snapping them across the stretched linen. Town along with William Ronald, Jock MacDonald, and Jack Bush, who are also represented in this show, were members of the Toronto group Painters Eleven from 1953 to 1960. Their respective experiments with non-objective imagery through the 1960s and 1970s carried the increasing authority that the New York art scene has exerted over this country’s visual arts since the Second World War’s close.

Undoubtedly the most highly regarded supporter of Abstract Expressionism and Post Painterly Abstraction in United States through the 1950s and 1960s was the New York City art critic Clement Greenberg, whose visits with artists in Central and Western Canada were considered monumental events. The unpremeditated rendering processes and juxtapositions of colour fields that he championed, with regard to the work of artists such as Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman, would reverberate in Canada for decades to come. Ron Martin’s employment of preconscious gestures to create Dioxidine Purple (see Image 1 above) appears as yet another innovation in the practice of non-objective imagery. However the lasting immediacy of action that the London artist’s 1971 acrylic on canvas displays is related to strategies employed by the Automatistes in the late 1940s. Paintings by Marcelle Ferron and Paul-Emile Borduas (see Images 2 and 3 below), who were members of the aforementioned Montreal collective, in this exhibition encourage viewers to embrace an idiosyncratic understanding of artistic impulses which stemmed from Surrealist manifestos published in Paris during the 1930s.

Montreal artist Rita Letendre’s oeuvre exemplifies the constant oscillation between the absence and presence of the subject in modernist Canadian painting. Her work of the 1960s is rooted in automatic methods and thus lacks any decipherable references, however by the mid 1970s she was producing paintings which were more firmly connected to natural incidences. The bold colours and sharp diagonal lines of her 1974 Istar (see Image 4 at right) suggest a radiating light source from beyond the canvas. Letendre’s membership in the Non-Figurative Artists’ Association of Montreal, which was established in 1956, served to inform her practice for decades as it did for fellow members Guido Molinari and Claude Tousignant. Although their respective paintings in this show from the late 1960s demonstrate a more complete rejection of Euclidean space in favour of hypnotic optical effects

Subtle variations of blue in Roy Kiyooka’s 1967 acrylic on canvas are used to differentiate two large oval shapes, and while the image does not proffer an overt bond to the world around us it is dependent upon a celestial occurrence. His title Eclipse (see Image 6, left) thus reveals the phenomenal basis for such a seemingly non-objective painting. Kiyooka’s early involvement with the artists who came to be known as the Regina Five in 1961 also articulates how abstract art’s reach extended beyond Canada’s metropolitan communities to impact regional urban centers.

Ron Bloore, a member of the above Regina group, became famous for his white on white paintings which includes the untitled work in this show that lacks both colour and subject. Among the artists featured in Absence or Presence who operated outside a collective setting is Alex Janvier. In the Dene painter’s 1972 acrylic on canvas As Strong As A Bull Skull (see Image 7 below) negative white areas take on cranium-like shapes that are offset by whiplash lines and pools of pure colour. Such an interplay links this work to that of another Alberta artist in the exhibition, Marion Nicoll, who taught Janvier at Calgary’s Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, and her manipulation of positive and negative space infers but never confirms a mountainous landscape (see Image 8, below).

By the late 1970s abstract painting was slowly losing its primacy of innovative place in Canada to practices such as installation, photography, video, and performance. Artists including Gary Neill Kennedy (see Image 4, above) who resided in Halifax, began to push the application of pigments on canvas in a more conceptual direction. However his meticulously created 1978 piece in the exhibition is not wholly unrelated to the mesmerizing colour field works from the 1960s mentioned earlier. Despite the apparent avant-garde failure of modernism through the 1980s, Toronto artist Gershon Iskowitz’s 1986 painting on display here (see Image 1, above) forcefully renews the investigation of key aesthetic problems. His flattening of the canvas’s traditional illusionary space and utilization of brilliant red, yellow, blue, purple, and green oils is part of the same project that the French Impressionists initiated during the late nineteenth century.

Perhaps Canadian art historian Mark Cheetham’s understanding of post-modern art’s compulsion with memory can explain why non-objective painters over the past decade have begun to revisit works by the Automatistes, Painters Eleven, Non-figurative Art Association of Montreal, and Regina Five. Edmonton-based artist Graham Peacock’s 1992 Aaron (see Image 9 above) boldly looks to the past in its unadulterated celebration of colour and texture, while his use of styrofoam supports, glass beads, and reflective plastic strips on an organic shaped canvas breaks into the future. Peacock is a member of the Canadian-American collective called the New Painters, and they are reasserting the ebb and flow of a subjective absence or presence in contemporary art making.

“It is not unusual to read about modernism’s absence of memory, its amnesia within a putatively pure self-presence.”

– Mark Cheetham, Remembering Postmodernism: Trends in Recent Canadian Art (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1991) p.24.

– Curtis Joseph Collins, Associate Curator

The accompanying brochure for this exhibition is available by going to the U of L Art Gallery’s PUBLICATIONS PAGE.

One thought on “Absence or Presence

January 24 – March 7, 2003

Main Gallery | Centre for the Arts | W600”