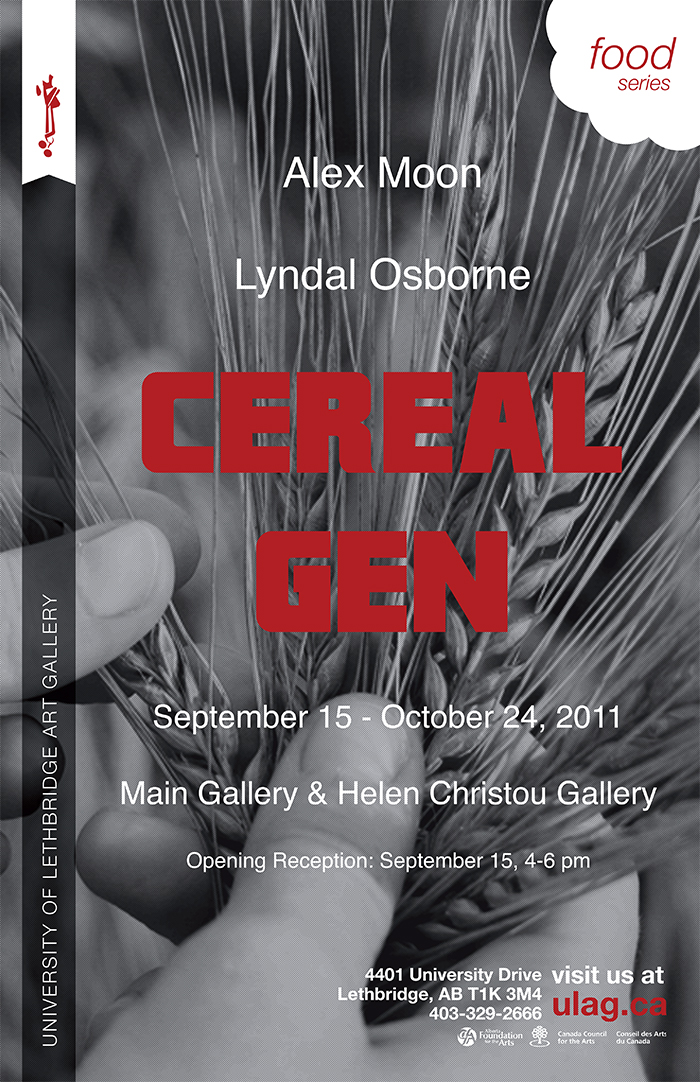

Cereal Gen (Food Series)

Main Gallery

Curator: Josephine Mills and Jane Edmundson

Planned in conjunction with Liberal Education course

Artists: Lyndal Osborne and Alex Moon (and works from the Collection)

Cereal Gen is the second exhibition in the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery’s Food series that runs June through December 2011. With three exhibitions and a public-site project, the series addresses social and cultural issues related to food production, supply and consumption. Green Thumb opened the series and featured works from the U of L Art Collection that explore gardens and greenery both in terms of pastoral imagery and political implications. Consisting of detailed installations that play with the forms and technology from scientific laboratories, Cereal Gen includes recent work by two Alberta artists and focuses on social and economic issues related to seed production and farming. Between October 1st through 6th, look for DodoLab’s project The Important Things to Know About Eating and Drinking In Lethbridge which will be appearing in several sites around campus. The Food series will conclude with The Lion’s Share, a new installation by Rita McKeough in which she playfully explores our relationship to eating animals.

Given the essential role that food plays in our lives as sustenance and as part of social and economic systems, it has been a common subject for artists to explore in their work. With the major changes in recent decades in the application of scientific processes and the relationship between individuals and corporations involved with food production and distribution, there have been heated debate and volumes of research on this aspect of food. Artists have engaged with this timely and important topic in many ways. Some take the role of activist and clearly critique genetic modification or the corporatization of agricultural production. Others, like the two artists in this exhibition, explore the fascinating imagery, complex emotions, and confident assertions of authority and certainty posed by corporations and scientific discourses that emerge within, and are part of, these debates.

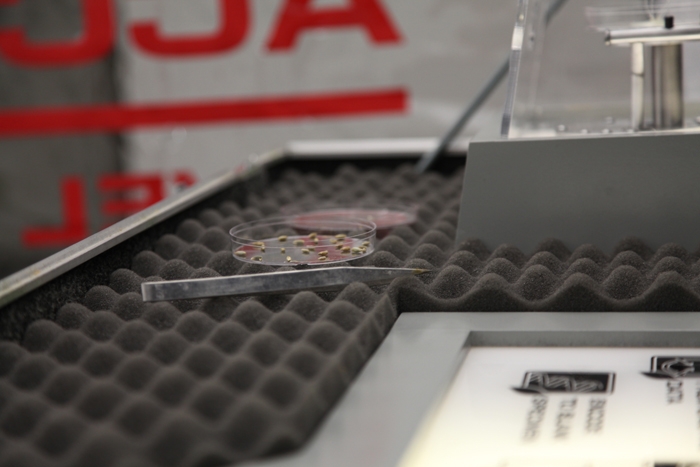

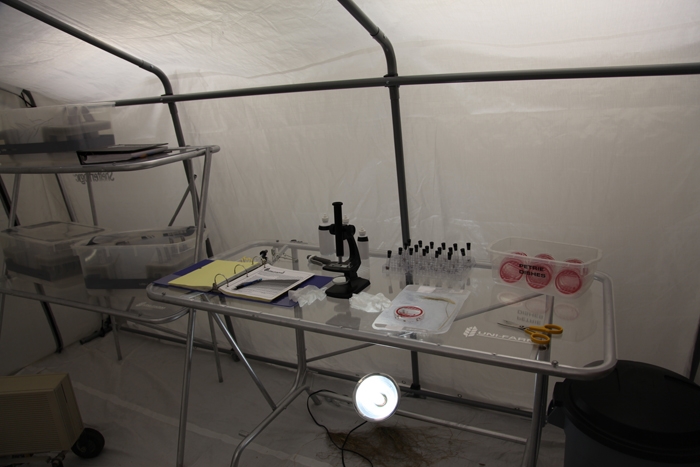

The title for this exhibition, Cereal Gen, is a play on words that references the subject of the works on display: “serial gen” is short for serial number generating software. In Alex Moon’s Uni-Farm project, a repurposed old dot matrix printer takes corporate branding to a new level and creates the seeds for his fictional corporation in the pattern of their logo. Moon cleverly questions the dominant assumption that technical progress intrinsically equals improvement in our health and well-being by using found objects, including old Macintosh computers, as the basis for the new-fangled devices and processes being promoted by Uni-Farm. Once the latest and greatest in technical advances, these devices and the surrounding climate of “progress at all cost” leads the employees of Uni-Farm, and the people of this fictional world to the precipice of worldwide food shortage. Moon further creates an awareness of the limitations on being current, let alone predicting the future, by using design elements straight out of a science fiction film. The colours, fonts for the text, and logo of Uni-Farm are all ordinary looking and thereby emphasize the ‘fiction’ part of science fiction.

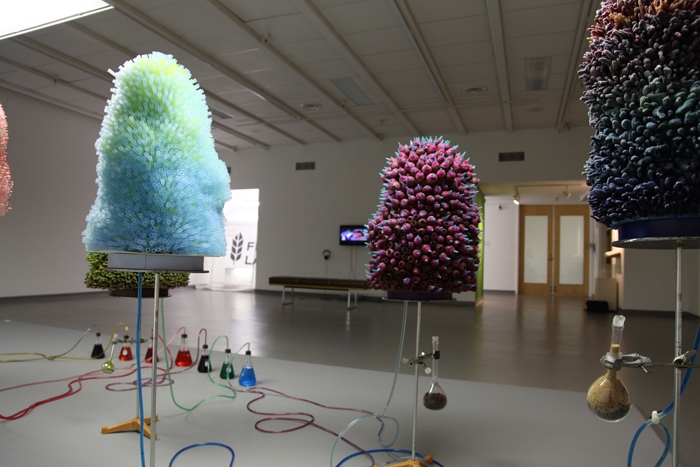

Lyndal Osborne’s installation also takes the form of a fictional laboratory, but not one where things are going as terribly wrong as Uni-Farm’s. The size, colour and detail of Endless Forms Most Beautiful immediately grabs one’s attention and demands closer inspection. Up close, the work is equally visually compelling with the combination of organic and inorganic materials to create massive versions of seedpods. Osborne describes herself as an “archaeologist seeking and retrieving discarded fragments of the urban environment and the dried out remains of natures’ seasons.” Although beautiful, as the name states, the mixing of items to create the seedpods, their strong colours, and their gigantic size disrupts the fascination with scientific imagery and disturbs an uncritical acceptance of the prevalence of genetically modified food.

Cereal Gen continues in the Helen Christou Gallery with more work by Moon as well as works from the U of L Art Collection. The Art Gallery would like to thank Bruce McKay for proposing the initial idea for the Food series. The exhibitions have been planned in conjunction with the Liberal Education Program which is currently offering a course titled “Food: A Critical Examination,” taught by McKay. As well, during this semester the new U of L Centre for Culture and Community will be presenting a speaker’s series on campus that will engage further with ideas and issues related to the social and political aspects of food.

Josephine Mills

Director/Curator

Artist Statement

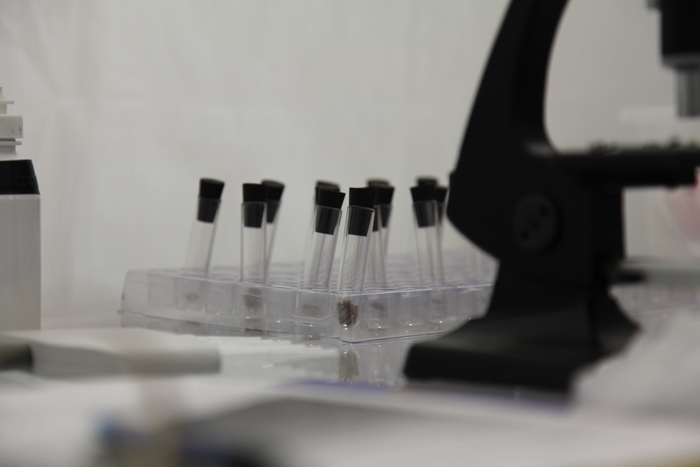

In my piece, Endless Forms Most Beautiful, the setting is a laboratory and the nine forms represent enlarged seedpods in the process of genetically modification. In GMO science three main techniques are employed for implanting genes into the seed cell – developing tumors, electricity, or a gene gun. In this imagined lab my forms reference these processes through the shape of the seedpod (with growths on the form), the materials used (pierced by electrical capacitors) and scientific equipment (pipets injecting DNA).

Many of the seedpods are created from actual seeds. In some cases the forms are seductive and beautiful. This represents the intellectual arguments used by the chemical companies to expand their research through the patenting of seeds (11 billion to date), gradually gaining corporate control of food production. There is also an element of the grotesque in other seedpods, suggesting a darker side to the shrinking of seed biodiversity. This hints at hidden dangers. Some genetically altered seed contains a terminator gene that ensues its infertility and lack of ability to reproduce. Could this government – patented suicide gene pollutes all crops around the world? What impact does this have on third world countries that no longer control the productivity of their own food?

The fictional laboratory created contains a small selection of heritage seeds (original, unaltered) that are set to one side. They exist as a miniaturized version of our past, something that is not available any more .The glass flasks and plastic tubing represent both an aspect of this genetic modification process and, more importantly, the interconnections we humans have with the plant world. I wish, as co-inhabitants of this earth we might agree to negotiate more checks in how far we go in our manipulation of the planet.

Lyndal Osborne