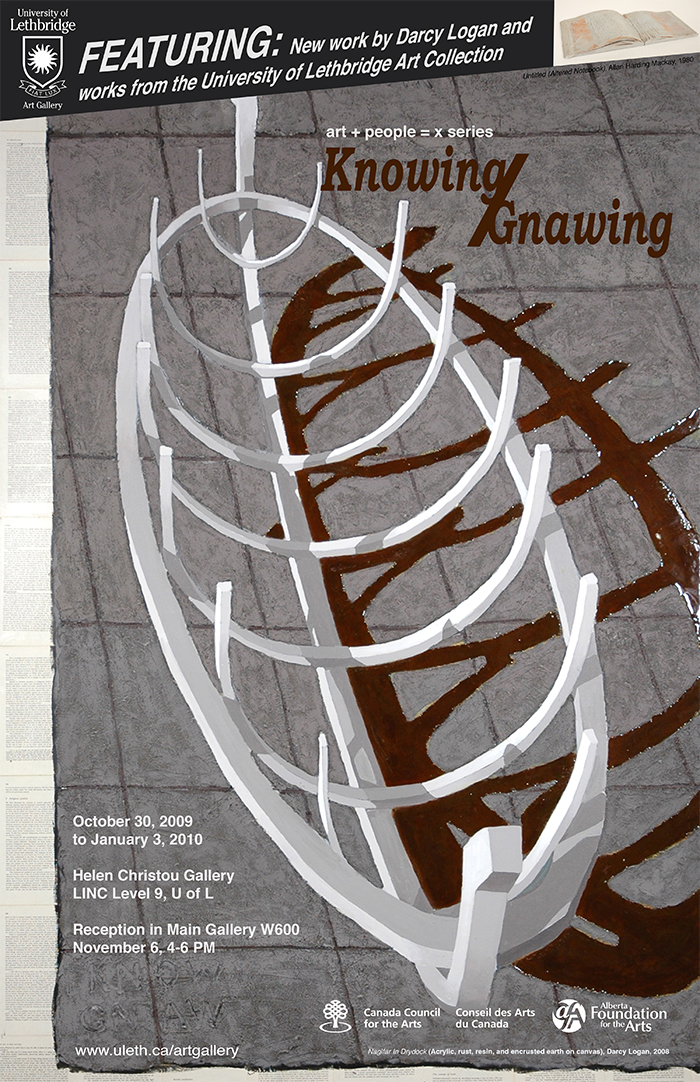

Knowing/Gnawing

Darcy Logan and works from the University of Lethbridge Art Collection

art+people=x series

October 30 – January 3, 2010

Helen Christou Gallery

Artist Statement: Know/Gnaw/Naglfar

My current body of work is titled “Know/Gnaw/Naglfar”, and uses myth as a metaphor to explore the nature of knowledge and ideas. In Scandinavian mythology, the Naglfar is a ship being constructed in the underworld. The etymology of Naglfar is from the Old Norse for “nail ferry”, which is both a metonym for the rivets that hold the planks together, and a description of its mythic purpose. The building materials for this ship are the finger and toe nails of the dead, the detritus of the body. When enough discordant people have died and the necessary amount of raw material has been gathered, the ship will be completed, freed from its moorings, and carry the forces of chaos to an eschatological finish for the world. This story provoked a string of associations for me, and gave me pause to reflect on how knowledge and ideologies are defined, hewn and constructed, and ultimately the consequences that follow in their wake. These are often disastrous, and can result from the excesses of philosophical and ideological certainty, or the dangerous limits of knowledge. The ship came to act as a metaphor for the individual and the body; limited, contained and forward moving. Some of the paintings approach these concepts literally, through direct references to history and the cannon of western philosophy, but just as often the approach is oblique, utilizing abstract texts and phrases to provoke associations in the viewer. The myth of the Naglfar became a potent symbol for me. The concepts and philosophies we record on the pages of history are like the planks of a ship, our words and sentences can act as mooring lines and cables, and the nails secure our intellectual aspirations and need to scratch out meaning from the world, whether for good or ill. The paintings are not illustrations of mythology, but attempt to use the tropes of poetry and myth as an alternative means of ingress into history and philosophy.

My works are as much assemblages as they are paintings. I use layers of encrusted earth, resins and rusting agents to create the finished pieces, referencing my interest in alchemical processes. I often carve directly into the drying mud, leaving parts of the work depressed, and others in high relief. Formally, I am interested in compositional tension. I attempt to explore and exploit normally incongruous elements on the canvas. These elements can be the tensions between the thick, matte appearance of the mud against the thin reflective quality of the resin, the tension between illusionistic representation and passages of implied abstract space, or the tension between the modern and primitive nature of the materials. I attempt to make my work experiential, and am striving to create works that require an immediate and personal engagement with the viewer. The textures and nature of the materials used subvert, and make exceedingly difficult, digital and mechanical reproduction. As a result the work can only exist as an experienced object. The accompanying images are a sampling from the numerous paintings, drawings and book-works in this ongoing series.

Darcy Logan

Curatorial Statement

“Substances occupy the mind by invading it with thoughts of the artist’s body at work. A brushstroke is an exqusite record of the speed and force of the hand that made it, and if I think of the hand moving across the canvas – or better, if I just retrace it, without thinking – I learn a great deal about what I see. Painting is scratching, scraping, waving, jabbing, pushing and dragging. At times the hand moves as if it were writing, but in paint…”

James Elkins, What Painting Is, Routledge 1999

The obvious way in which to construct an exhibition is to select works which have either a thematic resemblance, or which utilize similar visual or pictorial tropes. This is the surest way to ensure that an exhibition has the appearances of both visual cohesion and a modicum of curatorial rigour. While this can be aesthetically striking, and create permutations of meaning as varied as the individual viewers, it can also be unsettling if the various relationships between the works are forced or superficial. How does a painting speak to us when isolated from the bodies that are implicit in its construction; the body of the artist and the artist’s broader body of work? What content can we read into disparate paintings that have been amputated from their bodies, and stitched into a new one? How can we translate something meaningful from them besides an admiration for their skilful construction or a vague emotional evocation?

This exhibition presents an alternative opportunity to reflect on artistic production in a larger sense, outside the scope of individual artistic practise and its resulting products. It is the first step in a journey to begin thinking discursively around the idea of artistic praxis rather than the production of objects and begin, as historian James Elkins states, “..to think in paint, rather than about paint”(1). It reflects on the practice of art beyond the creator’s intent, and thinks about painting as both a material archive and ideographic history of ideas, time and labour which cannot be decoded, merely excavated. A record of the bodies that created them. In the end, this exhibition explores the idea of corpus. Just as the Naglfar paintings are symbolically about the individual and the body, the exhibition in a larger sense extends the metaphor to navigate an idea about painting itself as a corpus historicum.

Painting is an activity of the body, both literally and figuratively. It is created by movement in fixed physical locations. But painting is also excretory, a metaphorical activity of the body. It is a by-product of consuming ideas and ingesting experiences. These are digested as time is spent researching and working-out how best to convey a concept, but a painting as a vehicle to communicate these ideas is problematic. It must rely on traditional signifiers of meaning, such as titles, labels, artist statements, didactic texts, biographical information and its in situ relationship to the artists broader body of work. Without this apparatus it is arguable that the ideas the artist has digested have been excreted as something inert and faecal. Coloured dirt suspended in a binder, perhaps decorative or well crafted, but it’s meaning obscure. When the signifiers of meaning begin to get removed, so does our ability to decode and easily access the work. Not that a narrative meaning is integral to the success of a painting, but it is often the primary means of ingress into a work, whether the narrative is allegorical or whether it speaks to where the painting sits in the broader discourse of art. Some of the works in this exhibition give us very little in the way of decoding them, once stripped of many of the signifiers of meaning. An abstract image that refers to the landscape, titles that reference a work as a constituent part of larger set, vague references to cultural history and a series of gestural marks with cryptic and alluring titles. We have labels, an image and the artists names, what can this tell us about the works’ meanings? Not that a painting must mean something, but we still require a way to read them. Perhaps we can begin to read them as a narrative of a different kind.

If a painting is divested of the traditional apparatus of signification, and its meaning indeterminate, we are left with a tangible object that still operates as a codex, although it records and communicates something different to the way tradition and convention have conditioned us to read a painting. It communicates both its own physicality, and traces of the body. Bodies of work as records of the bodies that created them, bodies of knowledge fixed into the paint as free floating signifiers, and the audience made conscious of their own bodies stopped and fixed in space during the process of looking. The work of art becomes a complex ‘corpus historicum’, whose essential meaning can never be fixed. It is a knot whose myriad of thread are made up of histories, intentions, contexts and materials. Its surface is a script that archives successes and failures of communication, and while we can never fully unravel it, its very presence makes us aware of its physicality and gravity, and consequently, our own.

Darcy Logan

addendum: The altered encyclopaedias were made specifically for this exhibition, to work conjointly with the McKay books as a way to ‘read’ the exhibition. It was important to have this reading mediated not by traditional didactics, but by altered books as re-contextualized bodies of knowledge.

(1)Elkins, James, “What Painting Is”, Routledge, 1999

10 thoughts on “Darcy Logan: Knowing/Gnawing

October 30 – January 3, 2010

Helen Christou Gallery | LINC | Level 9”