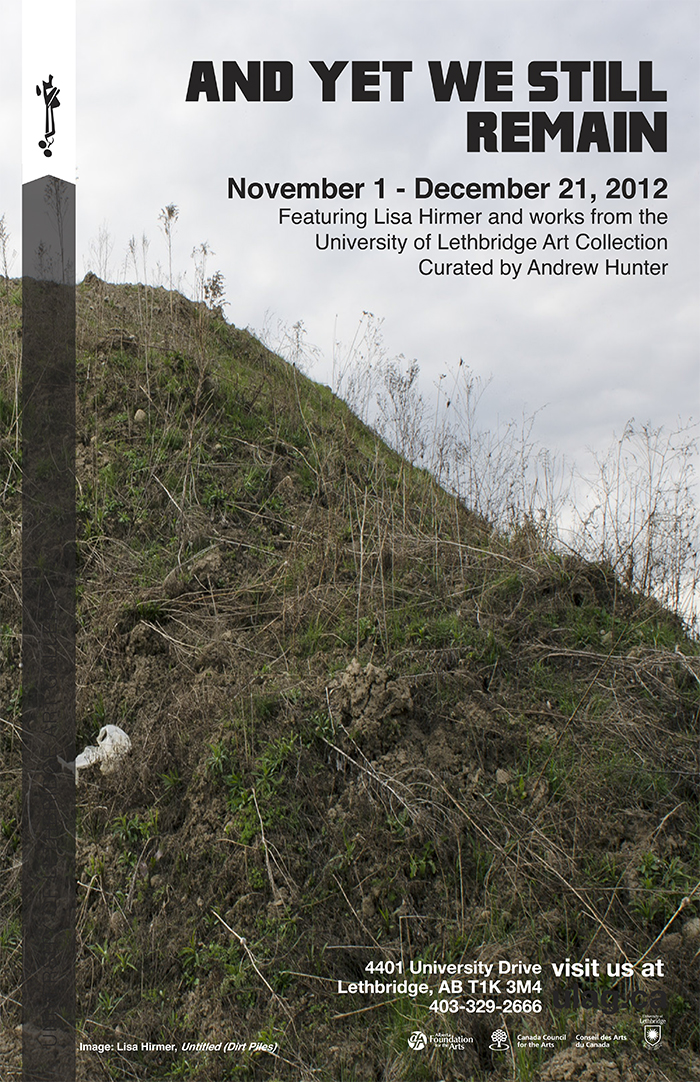

And Yet We Still Remain

November 1 – December 21, 2012

Main Gallery

Reception: November 1, 4 – 6 pm

Join us at the opening as we enjoy a slice of Dodolab’s Not Quite Famous Lethbridge Pizza

Curator: Andrew Hunter

Artist: Lisa Hirmer and works from the U of L Art Collection

And yet we still remain, going around, and again, in dominion’s plot…

A Mari usque ad Mare (“From Sea to Sea”)

Canada’s motto derived from Psalm 72:8 – “He shall have dominion from sea to sea and from the river unto the ends of the earth.”

For well over a century, the Canadian landscape has been an extensively manipulated one, dramatically transformed by industry, agriculture and urban development, yet it continues to be read, and often labelled as, wilderness. Post clearcut Algonquin Park, the managed forests of British Columbia and New Brunswick, the vast wheat fields of the prairies, are all prime examples of irreversibly altered terrain layered over with a skewed narrative of nature, one that remains nailed to the wall in many exhibitions, runs through tourism promotions and underscores populist political speech. This idea seems deeply imbedded in interpretations of the iconic landscapes of the Group of Seven, Emily Carr, Tom Thomson, and their peers, descendents and followers. Unsullied terrain, a pristine untrammelled wilderness, a resilient pure nature, is believed to be still out there. At the heart of this collaborative exhibition is a firm conviction that the persistence of this problematic narrative of the landscape offers a false comfort, a fantasy world of pure spaces that has become a risky dead-end narrative, a cul-de-sac where one can circle endlessly, spinning, and being spun, a pernicious tale that masks Canadians’ true relationship to the natural world.

Central to this exhibition are selections from Lisa Hirmer’s ongoing Dirt Pile series. Her photographs capture the extracted earth of engineered building sites that loom on the fringes of new construction, heaps of exhumed soil, rock and plant material often left forgotten and abandoned to be absorbed back into nature to become mound features in the landscape that are eventually read as natural. Hirmer’s framing of these fabricated features in the landscape suggests the signature images of Lawren S. Harris, his mountains, islands and icebergs of the 1920-30s, works that pushed him to abstraction, a space where few Canadians ultimately wished to venture (and so Harris remained trapped in a heroic nature-based story of a nation of his own making). More than simply documents of a marginal aspect of the built environment, Hirmer’s photographs stand as compelling statements, articulating a subtle iconic framing of subject matter, plotting a precariously detached, at times ethereal engagement with the landscape, a landscape with which Canadians remain ambiguously connected. They are positioned here with historical works from the University of Lethbridge collection and photographs by Lawren S. Harris (the source of his iceberg paintings). What this exhibition proposes is that Hirmer’s works are a far more authentic representation of the Canadian landscape, a terrain that has been consistently altered, shaped and manipulated, but that remains hidden behind a projection of a more palatable story of place.

We have changed the atmosphere, and thus we are changing the weather. By changing the weather, we make every spot on earth man made and artificial. We have deprived nature of its independence, and this is fatal to its meaning. Nature’s independence is its meaning; without it there is nothing but us. – Bill McKibben, The End of Nature, Random House, 1989, p.50

While our ways and means of shaping and transforming this world have continued to evolve and expand, no longer contained by specific geography or geology, the over-arching narration, the voice over to our film of Canada, has not changed. And this narrative also continues to be expanded and enhanced, now incorporating the absurd belief that we are capable of “restoring” the environment, that we can design and rebuild natural systems, as if nature can be put on hold, in storage, while we extract what we need. Perhaps the most glaringly disturbing example of this fantasy is the newly created Gateway Park on the edge of Syncrude’s massive operations in the oil/tar sands of Northern Alberta with its small and rarely seen herd of introduced wood bison that reside in a former wetland now “restored” as pine woods. Elements of the natural always return, as is so evident in a number of Hirmer’s images, but it is always less, less complex, less diverse, a weaker system. Some things always vanish. Some things can’t wait until we are done using the land.

The series of photographs by Lawren S. Harris are positioned here in direct dialogue with Lisa Hirmer’s work. This is the critical conversation, the connection that inspired And Yet We Still Remain. Harris took these images in 1930 while travelling throughout the eastern arctic with fellow Group of Seven member A.Y. Jackson on board the Beothic, a commercial sealing ship on loan to the RCMP and Canadian government researchers. From the ship (named for indigenous people of Newfoundland & Labrador pushed to extinction by Europeans), Harris photographed numerous massive icebergs, resulting in a set of images that would inspire such iconic works as Icebergs, Davis Strait, 1930 (McMichael Canadian Art Collection). He also photographed settlements and the Inuit, but this subject matter did not make it into his subsequent works, paintings that project a cold, empty, unpeopled and distant place that Harris believed was the real Canada, a place all true Canadians could identify with, although most would never go there. Distance is critical to the Canadian narrative of the land, stories of places conceptually embraced but rarely physically witnessed, rarely experienced as more than narrative or representation. Harris’s reified scenes continue to grow in value and retain their iconic status, but the real place no longer exists, is no longer out there, in the distance, pure. We can keep telling the story, but it doesn’t change the physical truth. We can spin consoling tales, but cannot resuscitate the natural systems no matter how much we design, plan, shape and attempt to hide or pretend we are still one with nature.

– Andrew Hunter, Guest Curator

Artist/Curator Biography

Lisa Hirmer is a designer/photographer/artist/writer based in Guelph, Ontario. She has a Bachelors of Architectural Studies and a Masters of Architecture from the University of Waterloo. Her masters thesis On Wilderness focussed on the significance of nature and wilderness in contemporary culture – work which won an Ontario Association of Architects Award of Excellence and was placed on the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada’s Honour Roll. Her photographic and graphic work has been exhibited in projects in Canada, Europe and the UK. Her photographs, which are often paired with writing (whether her own or that of a collaborator), have been featured in numerous publications including: OnSite, FUSE, Horizonte, PLAT and nomorepotlucks.

Andrew Hunter is an artist/writer/curator/educator based in Hamilton, Ontario. He has exhibited and published widely in Canada and internationally (including exhibitions at the National Gallery of Canada, Art Gallery of Ontario, Art Gallery of Alberta and Dubrovnik Museum of Modern Art) and has held curatorial and programming positions at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Kamloops Art Gallery and McMichael Canadian Art Collection. For a number of years, Hunter has been engaged in a critical exploration of dominant ideas and myths of Canada including such projects as The Other Landscape (exhibition and catalogue, Art Gallery of Alberta, 2003), Mapping Tom (published in the catalogue for the exhibition Tom Thomson, Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada, 2002) and Emily Carr: Clear Cut (published in the catalogue for the exhibition Emily Carr: New Perspectives, National Gallery of Canada/Vancouver Art Gallery, 2006). This exhibition can be considered an extension of his ULAG publication Cul-de-Sac, published in 2004, based on selections from the gallery’s collection and the touring exhibition Sea to Sky (curated by Josephine Mills).

Lisa Hirmer and Andrew Hunter are also principals of DodoLab, an art and design based program that researches, engages and responds to contemporary community challenges, with a focus on the natural world, social systems, the built environment and cities in transition. In 2010 they received a Canada Council for the Arts Independent Critic and Curators in Architecture grant for their collaborative project Marginalia.

One thought on “And Yet We Still Remain

November 1 – December 21, 2012

Main Gallery | Centre for the Arts | W600”