The Uncanny Valley

January 10 – February 28, 2013

Main Gallery

Reception: January 10, 4 – 6 pm

Curator: Jane Edmundson

Works from the U of L Art Collection

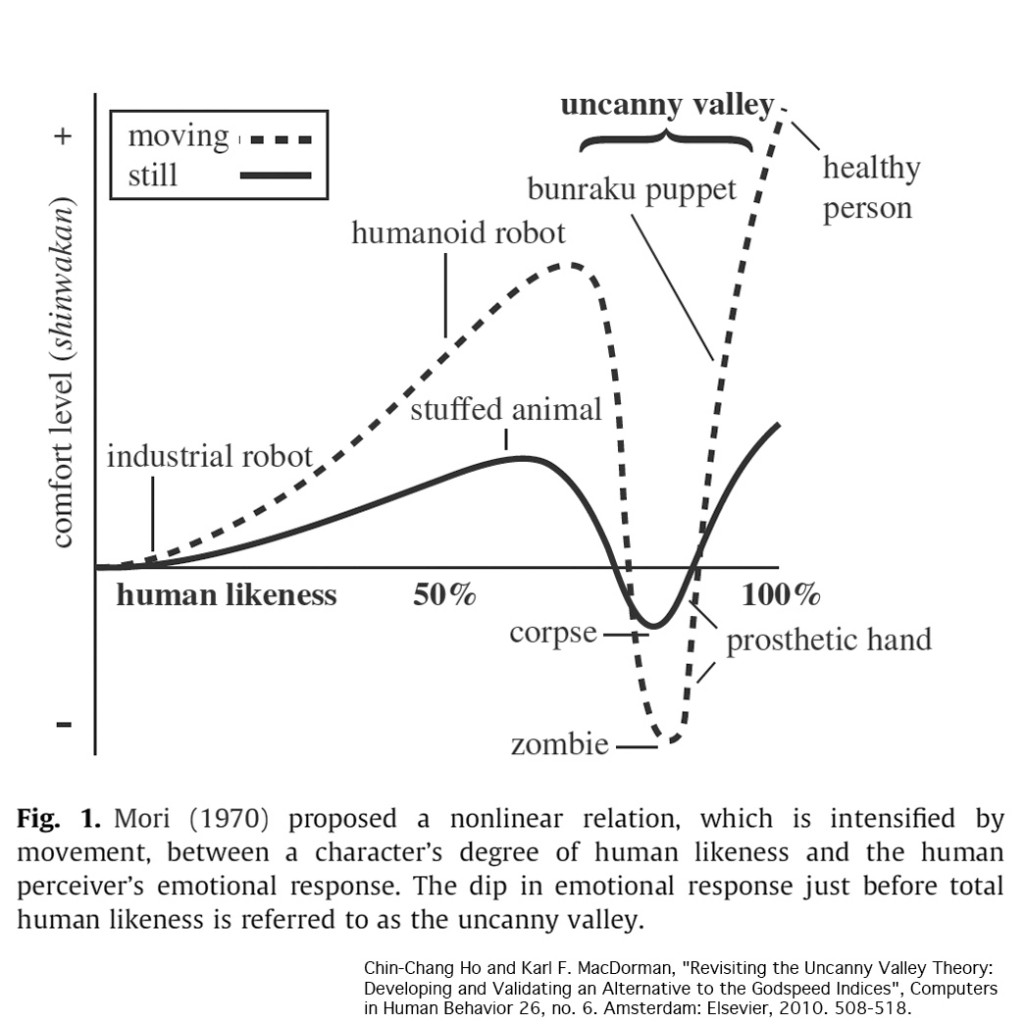

In his 1906 essay “On the Psychology of the Uncanny”, German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch describes the experience of the uncanny as “a lack of orientation”, where something happens that causes one to feel unease and alienation. This essence of discomfort is often brought about during the interaction between a living human body and lifeless objects which mimic the animate; in Jentsch’s day such incorporeal doubles included waxwork figures, realistic dolls and automatons. In the century since its first description, the opportunities for encountering the uncanny have multiplied exponentially, through the proliferation of mannequins in our limitless shopping malls, the development of artificially intelligent machines and highly efficient humanoid robots, the design and manufacture of anatomically correct “companionship” RealDolls, and customizable, personalized avatars in virtual reality games. Freud posited that the emotional disquietude that is felt upon interactions with these not-quite-human actors stems from our uncertainty at whether or not they indeed may be alive; this questioning dread was expertly tapped by George A. Romero in 1968’s gruesome satire, Night of the Living Dead, and continues in today’s mass zombie culture obsession. The humanoid imitations of life provoke increasing trepidation as they loom most closely to complete realism; the more convincing the fake and the greater familiarity and recognition of ourselves found in it, the more ghastly its void of  humanness becomes. The extreme drop in emotional comfort level upon the confrontation of lifeless objects that very closely mimic the animate was dubbed the “uncanny valley” by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970 (see Fig. 1).

humanness becomes. The extreme drop in emotional comfort level upon the confrontation of lifeless objects that very closely mimic the animate was dubbed the “uncanny valley” by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970 (see Fig. 1).

How is the uneasiness of the uncanny engaged in the interaction between the viewer and hyperrealistic artworks that depict the human form? The works selected for The Uncanny Valley display representations of humanness (or spaces remarkable for being devoid of humanity, in the case of Richard Estes’ painstakingly rendered, eerily empty cityscapes) that unsettle the viewer with their realism, which serves to heighten their dreamlike (or nightmarish) quality. These human bodies, flattened on canvas and paper, are frozen, hollow, and dead; the act of their creation by the artist’s hand also surmising their deficiency as mere imitations of life. Ivan Eyre and David Inshaw’s figures exist in abstracted, surreal realms that are at once familiar and alien, while Elsbeth Coop’s Prosthesis depicts a tense marriage of flesh and machine. Christopher Pratt, Barbara Pratt, and Jeremy Smith obscure the faces of their human subjects, and Jack Chambers’ Diego, as we are told, is sleeping rather than dead, but the inability to connect to the faces in these works nonetheless unnerves. Finally, David Barnett and Phil Richards employ the suspended forms of children, which have been used to great visceral effect in horror films about reanimation and ghostly apparitions, due in part to youth’s ability to remind the viewer of the ravages of time and their own mortality. The artists’ choice to render their human subjects in extremely realistic compositions draws us into these environments while concurrently inspiring apprehension and trepidation, as though we expect the depicted forms to suddenly move, grasping at the corporeal life they are denied by their illusory humanity.

– Jane Edmundson

Assistant Curator/Preparator