Main Gallery

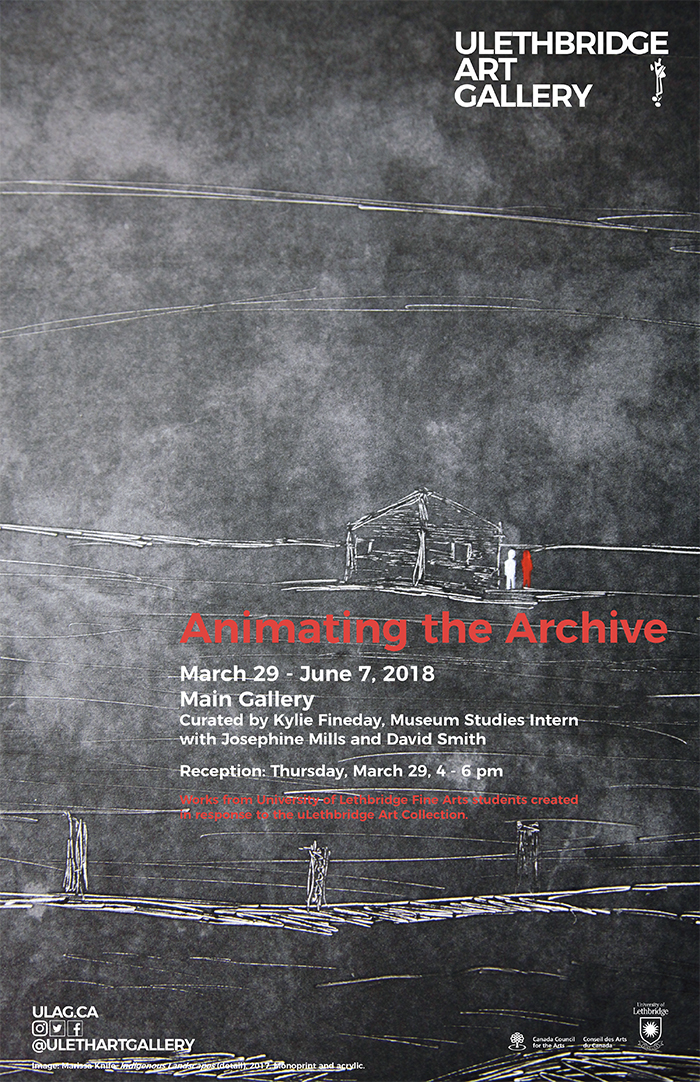

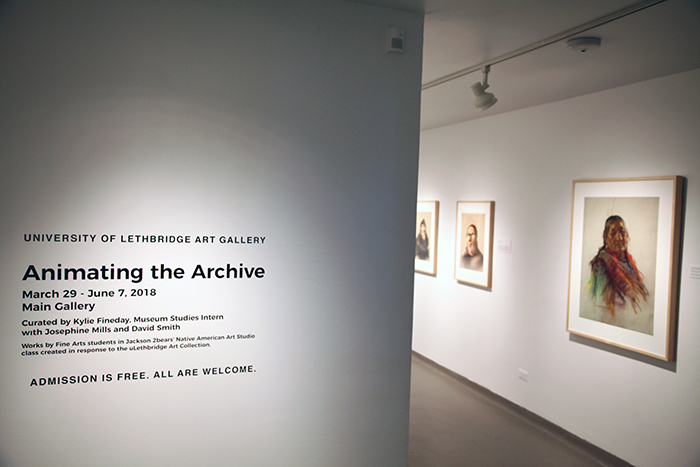

Animating the Archive

March 29 – June 4, 2018

Curated by Kylie Fineday, Museum Studies Intern

with Josephine Mills and David Smith

Reception: Thursday, March 29, 4 – 6 pm

Works from University of Lethbridge Fine Arts students created in response to the uLethbridge Art Collection.

This exhibition was inspired by the work of leading Indigenous artists such as Jeff Thomas who explore museum collections and archives and then produce their work to address the assumptions and practices within historical images about Canada, Indigenous people, and the land. Museum Studies Intern Kylie Fineday selected works from the 14,500 objects in the uLethbridge Art Collection to provide inspiration, reference, or context for the students enrolled in the Native American Studio class. The students then chose which works interested them and created a range of responses that build on this history and add contemporary perspectives to our collection. The exhibition includes works Fineday selected from the collection alongside the new work by the students.

Curatorial Statement

This exhibition consists of works selected from the collection of the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery along with art works made in response to them by students of the Native American Art Studio course, under the instruction of Assistant Professor Jackson Twobears. The art gallery houses a collection of over 14000 works, making it one of the most important collections in Canada.

For a student intern and first-time curator, the task of selecting works from the collection for this exhibition was a daunting one. While navigating the extensive and diverse collection through the digital database, I focused on selecting works that I felt had relevance to the subject matter of the Native American Art Studio course, which addresses such topics as: assertions of Indigenous identity, the colonial context in Canada, contemporary Native perspectives in art, and performative strategies of creative resistance. I chose to include works by Indigenous artists of various backgrounds and practices, works by settler artists that are representative of Indigenous people and culture, as well as works that address themes of land and nationalism. Given that this institution is located on the traditional territory of the Blackfoot, I felt that it was also important to include works with depictions of the local landscape.

As an art student of Cree heritage, I believe that representation of Indigenous perspectives within art institutions is of great importance. I hoped that the works I selected would allow for a variety of responses from the students, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, to build on the history of the collection works and incorporate fresh perspectives. From the selected collection works, the students chose the ones that interested them the most, and created new art works in response. The student-made works, displayed alongside the collection works, depict enlightened responses to the history of Canada’s colonial legacy as well as contemporary portrayals of Indigenous perspectives.

– Kylie Fineday, uLethbridge Fine Arts Museum Studies Intern

Animating the Archive: Stories for the Collection

Curatorial Essay by Kylie Fineday

Special thanks to Dr. Devon Smither for her support and for allowing me the opportunity to write this essay as part of a course assignment.

Animating the Archive arose from a desire to address the need for increased representation of Indigenous perspectives in cultural institutions. This is particularly important at a time when the celebration of Canada’s colonial legacy is coming more into question through education, as well as in the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission which address the residual problems from the traumas of the residential school system. The idea for this exhibition was inspired by Jeff Thomas, among other leading Indigenous artists, whose photographic practice often explores museum collections and archives in order to produce work in response and to address the assumptions within historical images about Canada, Indigenous people, and the land.1 . Animating the Archive was executed in collaboration with Professor Jackson Twobears and the students in his Native American Art Studio course.

From the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery collection I chose a selection of art works by Indigenous artists of various backgrounds and practices, works by settler artists that represent Indigenous people and culture, as well as works with themes related to land and nationalism. The collection contains over 14,000 objects, so the task of navigating the database was daunting for me as a first time curator. I wanted to focus on works that were relevant to the content of Professor Twobears’ course, which addressed topics such as: assertions of Indigenous identity, colonial history in Canada, contemporary Indigenous perspectives in art, and performative strategies of creative resistance. From the artworks selected from the collection, the students in Twobears’ class, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, chose the ones that interested them the most, and responded by creating new art works. With the help of Josephine Mills and David Smith, from the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, the display and curation of the both the collection and student works were carefully considered. The collection works were placed in conversation with those by the student artists to reveal a dialogue between contemporary artists and Canada’s colonial history.

The concept of this exhibition engages with the notion of dialogical curatorial practice, as outlined by Leanne Unruh, in the sense that I set up a dialogue between the collection works and the student art works. Unruh describes dialogical methods as a way to “challenge the traditionally imperial nature of museums in colonized countries.”2 Defining such a practice as involving conversations and collaboration with Indigenous communities, Unruh describes specific examples in which dialogical methods have been used to effectively allow for better understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups, and Animating the Archive follows that model.3 As a Cree student and artist, I felt that my involvement as a curator was important in allowing for Indigenous voices to be heard over Western discourses.

One part of the exhibition that is particularly exemplary of this notion of dialogical practice is the smaller gallery space containing portraits by Nicholas de Grandmaison from the collection and those made in response by student artists Suzanne Landry and Rachel Klaus. The University of Lethbridge collection boasts an extensive collection of de Grandmaison’s work, including archival records as well as his artworks.4 De Grandmaison worked closely with the First Nations pwoples whom he painted; they befriended him and even honoured him through ceremony, making him an honorary member of the Piegan Tribe.5 The exhibition features five de Grandmaison portraits of Indigenous subjects, at various stages of completion. Unknown Indian Study (Woman) is a partially completed study of an Indigenous woman. Though it is not a finished portrait, there are layers of pastel over the preliminary charcoal sketch, revealing the artist’s process for developing the portrait. We can see the face of the woman, her hair in two braids, floating in the centre of the picture plane. Another de Grandmaison portrait in the space, Unknown Indian Study, is a preliminary charcoal sketch, without any of the pastel colours he would add on later. It features an Indigenous man, his striking gaze looking straight at the viewer. The grid that the artist used to lay out the image is visible, making it clear that this is a preliminary study. Between these two portraits is the work by student artist Suzanne Landry, who chose to respond to de Grandmaison’s work with her own series of portraits. Like de Grandmaison, Landry used the practice of drawing as a way to get to know her subject: her own grandmother, whom she has never met. Landry’s nineteen portraits are based on photographs and they are also in varying stages of development and, much like the de Grandmaison works, read like preliminary studies.

Rachel Klaus, another student artist who chose to respond to Nicholas de Grandmaison, took a different approach. Her series of four portraits, each of a close friend, are closer in scale to the de Grandmaison works. However, using digital media to create her portraits which appear in the exhibition as framed prints, she brings a contemporary approach in her response to the collection. Each of her portraits is of a young woman she knows, digitally rendered against a background similar to the natural tone of the paper used by de Grandmaison. Her series is displayed between three of de Grandmaison’s more developed pastel portraits, each a depiction of a First Nations woman.

One of the Indigenous artists from the collection featured in the exhibition is Daphne Odjig, whose serigraph prints portray stylized figures within a variety of narratives. Comforting, a print by Odjig from her 1980 series Homage to Grandfather, is displayed in the main gallery space and consists of a large abstracted seated figure, cradling two smaller figures. The primary and neutral colour palette is muted, and the figures are defined by smooth, black outlines. Belonging, another print from the same series, is featured in one of the panels outside the gallery entrance. Odjig’s prints are an exploration of her cultural heritage and include narratives from traditional stories as well as expressions of important cultural values.6 Student artist Raylene Young Pine chose to respond to Odjig’s works through painting as well as an audio installation. The work is titled Enlightenment and is an expression of her personal experience with education and her Blackfoot culture. One of the two paintings represents her experience in the residential school system, and portrays abstracted figures in a style similar to Daphne Odjig’s. Young Pine also included three audio recordings, two of which are traditional stories being told in Blackfoot, and the other is a lullaby song. The stories are meant to teach important lessons that reflect Blackfoot cultural values. The song also represents the traditional value of nurturing young children. In speaking with Raylene Young Pine about her work, she described the process of making these works as a way of healing herself and moving forward, hence the title, Enlightenment. The fact that her painting addresses her experience of residential school, a system which was meant to assimilate Indigenous people across Canada, and is displayed with audio recordings of Blackfoot stories and song, is indicative of Indigenous survival, and the resilience of Indigenous cultures, and of Young Pine herself.

Featured on the exhibition poster is a print by student artist Marissa Knife. For her contribution to the show, she made a series of monoprints in response to a work by well-known Japanese-Canadian artist Takao Tanabe. Tanabe’s ink on paper work, Prairie Hills with Cloud, depicts a flat, empty, brown and black expanse of land beneath a dark sky with large clouds. Tanabe’s approach to landscape is through formal simplification of the natural and organic.7 Curator Darrin J. Martens suggests that Tanabe’s prairie landscapes represent perfection and are an embodiment of the Canadian landscape tradition.8 The link between landscape and Canadian identity has long been a defining factor in Canadian art history, with the celebration of landscape artists who portray the fictional narrative of Canada’s wild and untouched land, free for the taking. Marissa Knife responds to Tanabe’s work with her own series of monoprints depicting local scenes from the Standoff reserve. Instead of the romantic, empty landscape, these prints are filled with signs of human interaction with the land. There are fence posts and bails, as well as architectural structures. The black and white prints are punctuated with small figures, painted on with acrylic in traditional Blackfoot colours inspired by the medicine wheel. Her prints are an assertion of the presence of Indigenous people in the contemporary landscape. Four prints from Knife’s series are hung between the Tanabe landscape and a photograph by Jeff Thomas, The Delegate Visits Indian Battle Park, from his series, Indians on Tour. Thomas’ series operates similarly to Marissa Knife’s, in the placement of Indigenous figures in landscapes. Thomas takes a more humorous approach in his photographs, however, by using toy figurines and photographing them in front of various landmarks. The Delegate Visits Indian Battle Park features a small, plastic figurine of an Indigenous man in a feather war bonnet, dressed in regalia and holding a rifle, with Lethbridge’s High Level bridge in the background. There is a strong sense of assertion of Indigenous identity in both Thomas’ photograph and Knife’s prints. Given the conversation that Thomas’ photograph opens up about Indigenous representation, stereotypes, and landscape, the inclusion of his work within the exhibition was important and folds back to the curatorial framework behind Animating the Archive.

All of the works by the student artists provide contemporary insight and perspective in relation to the works from the collection, such as those by Alex Janvier, Margaret Shelton, and Norval Morrisseau. As a first-time curator, the experience of being involved in creating this exhibition and collaborating with Jackson Twobears and his students has been incredible. This exhibition is an important step, not only in my own professional development, but in the institution’s progression towards the notion of reconciliation. The fact that it was preceded by a solo exhibition by female Indigenous artist Meryl McMaster also speaks to the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery’s desire to provide a platform for contemporary Indigenous perspectives and voices, which I feel is very important.

Endnotes

1. Josephine Mills, “Animating the Archive,” University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, March 16, 2018, http://sites.ulethbridge.ca/artgallery/?p=16531

2. Leanne Unruh, “Dialogical Curating: Towards Aboriginal Self-Representation in Museums,” Curator: The Museum Journal 58, no. 1 (January 2015): 77.

3. Unruh, 80.

4. Gordon Snyder, Drawn from the Past: Nicholas de Grandmaison, (Canada: Snyder Fine Arts, 2007), ii.

5. Snyder, i.

6. Morgan Wood, Daphne Odjig: Four Decades of Prints (Kamloops: Kamloops Art Gallery, 2005), 19.

7. Darrin J. Martens, “The Presence of Absence in Takao Tanabe’s Prairie Drawings,” in Chronicles of Form and Place: Works on Paper by Takao Tanabe, ed. Jennifer Crane (Burnaby: Burnaby Art Gallery, 2012), 69.

8. Martens, 71.

Bibliography

Martens, Darrin J. “The Presence of Absence in Takao Tanabe’s Prairie Drawings.” In Chronicles of Form and Place: Works on Paper by Takao Tanabe, edited by Jennifer Crane. Burnaby: Burnaby Art Gallery, 2012.

Mills, Josephine. “Animating the Archive.” University of Lethbridge Art Gallery. March 16, 2018. http://sites.ulethbridge.ca/artgallery/?p=16531

Snyder, Gordon. Drawn from the Past: Nicholas de Grandmaison. Canada: Snyder Fine Arts, 2007.

Wood, Morgan. Daphne Odjig: Four Decades of Prints. Kamloops: Kamloops Art Gallery, 2005.

Unruh, Leanne. “Dialogical Curating: Towards Aboriginal Self-Representation in Museums,” Curator: The Museum Journal 58, no. 1 (January 2015): 77-89.