Helen Christou Gallery

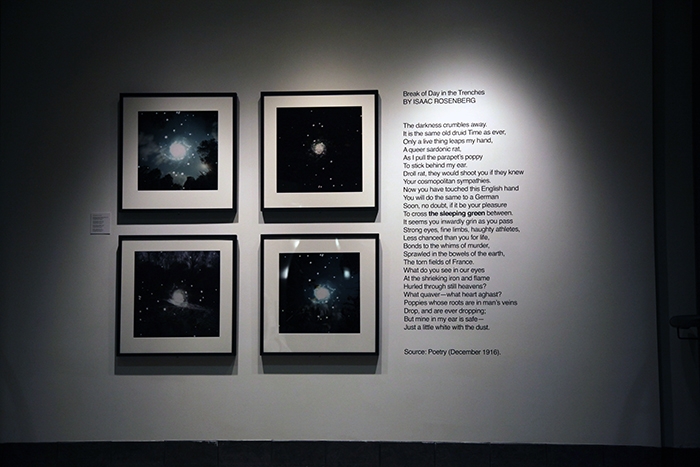

The Sleeping Green: no man’s land 100 years later

October 30 – December 23, 2015

Artist: Dianne Bos

Paratext by Harry Vandervlist

Curated by Josephine Mills

Calgary-based artist Dianne Bos references a famous WWI poem for the title of this exhibition which consists of extraordinary photographs taken in ‘no-man’s land’ between the trenches on the Western Front. Travelling through France and Belgium in 2014, Bos used a variety of vintage and pinhole cameras, including a 100 year old camera, to photograph the land a century after the Great War started. The results of her project are stunning, beautiful, and haunting; the photographs bring the emotions of this crucial historical period to life for contemporary audiences. As well, University of Calgary English Professor Harry Vandervlist contributes a small selection of significant poetry collections from the war years, in original editions. Alongside these historical texts appear his own contemporary writings in the form of montages and meditations which respond to significant phrases from the wartime texts, and which also resonate–in theme and in technique–with Bos’ images.

Curatorial statement:

Dianne Bos references a famous WWI poem for the title of this exhibition which consists of extraordinary photographs taken in ‘no-man’s land’ between the trenches on the Western Front. Travelling through France and Belgium in 2014, Bos used a variety of vintage and pinhole cameras, including a 100 year old camera, to photograph the land a century after the Great War. On returning back home to Calgary, Bos further worked with the images by incorporating objects from the battle sites – such as rocks, leaves, and a bullet – in the printing process. By scattering these over the paper during printing, as well as dodging, burning, and overlaying maps of stars, she produces layers of imagery that convey the emotional depth of these extraordinary landscapes. As Bos says, these works “make the invisible visible” and they represent far more than just depicting the physical features of the land as it appears today. In this way The Sleeping Green is not about the war itself: the exhibition explores how a terrible historical event has become part of the fabric of our collective imagination.

As is well known, WWI was a critical turning point on many levels, including in the development of the identity of Canada. The horrors of the new forms of warfare, along with the social and political importance of a war that dragged on for four years, has meant that the Great War still occupies a prominent place in Canadian and European thought even though there are few people left who were alive during the period. Bos engages with the concepts and the emotional resonance of WWI through the specifics of photography. She pushes the boundaries at all stages from the means of taking the image through to interventions in the printing phase. The resulting photographs are stunning, beautiful, and haunting; they capture the imagination of the viewer and evoke the impact that this crucial historical period continues to exert.

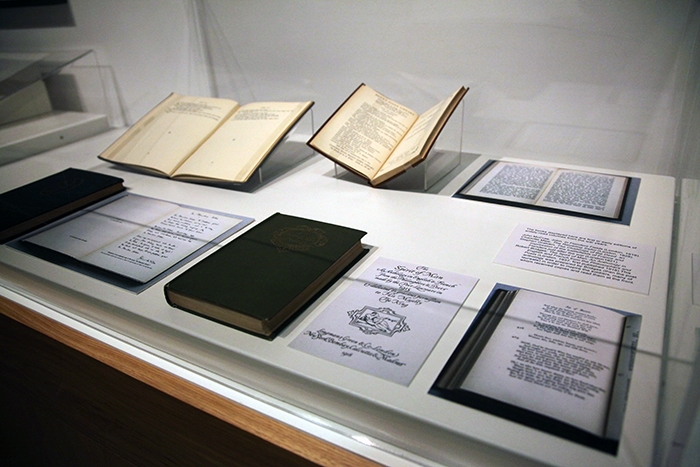

Further developing the connection between the war, the land, and the imagery, University of Calgary English Professor Harry Vandervlist contributes a selection of significant poetry collections from the war years, in original editions, to the exhibition. Alongside these historical texts appear his own contemporary writings in the form of montages and meditations which respond to significant phrases from the wartime texts, and which also resonate–in theme and in technique–with Bos’ images.

The Sleeping Green is not a commemoration of the events from 100 years ago. Instead, the exhibition explores how WWI lives on for those who have experienced only the stories and the images after the fact. It was important to Bos that she take the photographs in 2014 – that she walk along the Western Front a century after the war started and then produce works that would speak to the powerful feelings connected with the land that bears the scars of the horrific battles. The combination of Bos’ photographs, the historical volumes of poetry, and Vandervlist’s texts address how WWI exists in public memory and will influence the next generations through being an integral part of a collective imagination.

– Josephine Mills, Director/Curator, U of L Art Gallery

Artist Statement

August 2014 marked the 100th anniversary of the beginning of WWI. I live part of each year in a village in France, where every village, no matter how small, maintains a monument to honour the men from that area who died in WWI—always in numbers far greater than in WWII. What did I really know about that war, and its impact on the world today?

During the spring of 2014 I started researching and photographing WWI battle sites in France and Belgium that were significant and deadly for the Canadian forces in the war. I’ve focused my attention on the front lines at Ypres, Passchendaele, Vimy and the Somme.

For years my art practice has been to photograph sites using exposures so long that things that move, living things, disappear from the image. A passage of time is captured rather than the decisive moment.

I’m fascinated by the history of photography and the ways different devices change our perception of time and space. Using pinhole and vintage cameras I wanted to see how time has changed the landscape of these historic battlegrounds 100 years later. In ways other than the presence of memorials, does a memory of that past persist at these sites?

Using traditional photographic techniques, manipulation of light in the darkroom and objects found at the sites (a technique called photograms), images were created that layer site documentation and symbolic imagery. The real and the imagined combined to somehow portray memory and loss.

In the darkroom I manipulated light with my hands to create holes in space and maybe time: vignetting creates an escape tunnel or a gun barrel view channeling light into the landscape; darkness continues to hover above the marshy bog of Hill 60; a galaxy of stars spins overhead. The last light seen on a fatal night, or the constant light that guides us?

I stare into a field of potatoes, next to a WWI cemetery, land once called Sanctuary Woods, and wonder at how the earth suffers our great human tragedies and continues to be so generous.

– Dianne Bos

Dianne Bos would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts towards the production of this body of work.

Fields, in Flanders, 2014

by Harry Vandervlist

1. “Covering / earth”

To stand in the same spot on earth where barely imaginable suffering took place, 100 years earlier; does it bring any understanding? Can the imagination feel itself touched by echoes in the shapes of the land, the movement of clouds, the angle of light? To scoop a handful of that dirt or stretch out on that ground—do these things prompt a communication, a connection?

These fields have all been ploughed for 100 seasons. Yet vestiges still surface.

By selecting and arranging some such vestiges, some impressions, is it possible to receive something from the past, or re-create something in the present? An appreciation, an experience that renews . . . what? Perhaps only the sense of ignorance and distance. Perhaps a flicker of comprehension, a bare inkling.

And what if the terrain consists, as it does for me, of writing as much as of soil? Poems, memoirs, slogans, also ploughed over, repeated and re-interpreted until the echoes cancel each other in a fog of white noise. What still haunts, resounds, after nearly 100 years of flipping pages, or allowing pages to moulder, unread, on a shelf?

Words repeated and turned over in the mind can lose all meaning: anyone can, like Samuel Beckett’s Watt, turn “little by little, a disturbance into words” can make “a pillow of old words, for his head.” A pillow, or a blanket of words like the flowers in Ivor Gurney’s poem “To His Love,” which memorialize in order to forget, if possible:

“You would not know him now…

But still he died

Nobly, so cover him over

With violets of pride

Purple from Severn side.

Cover him, cover him soon!

And with thick-set

Masses of memoried flowers-

Hide that red wet

Thing I must somehow forget.”

Yet deliberate efforts of remembrance — remember this, so that can be forgotten — however energetic, on whatever scale — however strenuously maintained and reinforced — always find themselves undermined. Up from below surge reminders, “scattered things” . . ..

_________________________________________________________________

Magical dream of war’s end #1

Throughout this trip the dreams have been vivid. Last night it was a big hall we were in, some kind of mansion or chateau . . . But it feels like it’s not a private home, and little groups of men are whispering together in the corners. They’re in uniform. It’s a hospital, a military hospital, and I can hear them talking about news that’s arriving.

“He hasn’t been seen in days, but there’s a stream of doctors going in and out. There’s no official announcement, just utter silence. Obviously a great deal of concern. It’s worse than bloody bad news, the silence.”

A newcomer joins in. “Well you won’t like the bits that I’ve heard, and quite frankly I don’t know what to believe myself. But a chap who’s been in the room says his face is completely bandaged. Just the eyes and mouth exposed. And he’s eaten no solid food for days now. It’s preposterous I know . . . you’re thinking, we’ve seen a bit of that ourselves. Battlefield stuff, shrapnel to the face, jaw gone, cheeks all shattered. Les geules cassées they’re calling them in France, poor bloody chaps who wish they’d simply died. But the king himself, who’s been kept well out of range? These are the kind of rumours we’re going to get if they won’t put out any kind of statement I suppose.”

When I hear the words “les geules cassees” I find myself outside the building on a huge lawn. There are lounge chairs under trees and nurses walking with people. I join a small group as if I’ve always known these men. They’re in uniform, but none of these soldiers are Europeans—they’re Arab, African, North American native men. Their expressions are serious. I can’t hear them clearly even though I’m standing right there, but they seem to be saying that yes, it’s working, and no, the news will never come out. It’s working because they’re all related, all the kings and dukes, the Austrian emperor and so on. They’re cousins, it affects all of them the same way. None of them has been seen for days. The news will never come out but the war will be shorter. Now they will try harder to stop it.

In the dream I know that these men are shamans, concerned about something they have done, eager to stop it, but also hopeful. They have invoked a sympathetic reaction, somehow Europe’s kings now share the most terrible wounds of their soldiers. They will start to recover soon, it will all remain a mystery but something will have changed. They will agree to end the war soon. The world will never know.

_________________________________________________________________

2. “Into cleanness leaping . . .”

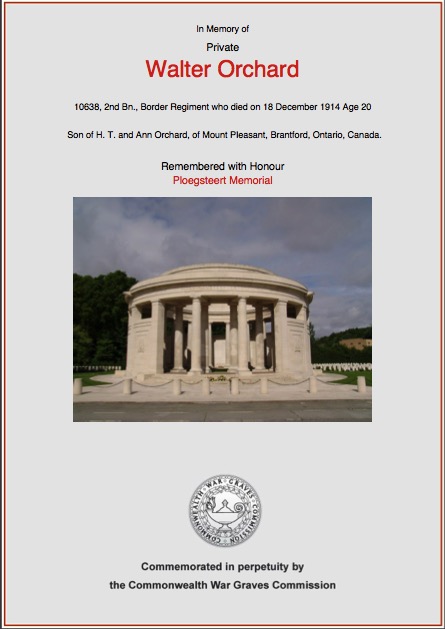

“The Ploegsteert Memorial stands in Berks Cemetery Extension, which is located 12.5 Kms south of Ieper town centre, on the N365 leading from Ieper to Mesen (Messines), Ploegsteert and on to Armentieres.”

-Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Cemetery Details

The first thing you notice at Ploegsteert Memorial is the order. The order and the cleanliness. White stone gleams in the sun. Carefully nurtured flowers decorate the graves, and the names chiseled in the the memorial wall seem freshly carved, dusted that morning. In the Visitor’s Book kept behind a bronze door in a niche, all the visitors express gratitude for how beautifully maintained they find this place commemorating their grandfather, great-uncle, great grandfather, uncle, older brother. For me, it’s my great-uncle, my maternal grandfather’s older brother Walter Orchard, who brings me here.

Walter’s name appears among the names of 11,366 identified casualties at the memorial. He has a place on Panel 6 of the sunlit curved wall of white stone. The geometric order of the memorial, the solid stone construction, the painstaking maintenance of the site, all create a sense of repose. Of order.

Is this the cleanness into which Rupert Brooke, in his 1914 sonnet “Peace,” saw soldiers, like swimmers, gladly leaping? Well-swept stone and well-weeded flowerbeds. Graves plotted on Cartesian axes, Roman columns that draw the eye skyward.

Did Walter experience a calm, orderly and dignified sacrifice of his body in the name of those abstractions named in Robert Bridge’s poetry anthology The Spirit of Man? “From . . . the insensate and interminable slaughter, the hate and filth, we can turn to seek comfort only in the quiet confidence of our souls; and we look instinctively to the seers and poets of mankind, whose sayings are the oracles and prophecies of loveliness and lovingkindness.” Turn away from men’s bodies and their suffering, Bridges admonishes, and look to the spirit embodied in English verse.

The nature of the memorial suggests Walter’s life ended in circumstances that partook more of the first part of Bridges’ phrase, than the second part: “The Ploegsteert Memorial commemorates more than 11,000 servicemen of the United Kingdom and South African forces who died in this sector during the First World War and have no known grave. . . . Most of those commemorated by the memorial did not die in major offensives, such as those which took place around Ypres to the north, or Loos to the south. Most were killed in the course of the day-to-day trench warfare which characterised this part of the line, or in small scale set engagements, usually carried out in support of the major attacks taking place elsewhere” (Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Cemetery Details).

I like to think that the phrases “no known grave” and “killed in the course of the day-to-day trench warfare” did not appear in the death notice my great-grandparents received in Manchester, just in time for Christmas 1914. Those phrases tell a story of chaos and confusion, not of order. Of soldiers simply lost in the coming and going, killed outright or possibly injured and abandoned, no one knows where. Men who went out, somewhere, and did not come back. A silence at roll-call, a question mark in a ledger, a body lost track of. No known grave: the remains of my grandfather’s brother, along with those of 11,366 others, merged with those “scattered things,” all the clutter of organic and inorganic detritus spread over the fields of France and Belgium. Nearly 2,300 legs, or feet, or boots, or testicles. That many eyes.

Charlotte Mew wrote:

“Surely the Spring, when God shall please,

Will come again like a divine surprise

To those who sit today with their great Dead, hands in their hands

Eyes in their eyes

At one with Love, at one with Grief: blind to the scattered things

And changing skies.”

Ezra Pound pictured eyes as well, “Quick eyes gone under earth’s lid.” Making these fields of potatoes and cabbages, where I stand today, an enormous earthen eyelid pulled down over all those thousands. Staring at the sky, or ground into the earth.

That’s what I see now as I cycle slowly across these fields, into the woods . ..

The reassuring order of the Ploegsteert memorial, and the precision of a specific date, barely a week before Christmas, have a reassuring effect—as long as you don’t inquire into phrases like “no known grave,” and as long as you don’t consider the absurdity of murder planned and executed on an industrial scale, then piously halted for a “Christmas truce,” then resumed. Because this violent absurdity could not, must not, be given space in the public mind, an apparatus of recovery and memorialization needed to be invented. ““The novel phenomenon of mass ‘death at a distance’ had forced the British people into an encounter with a particular aspect of grief, that complex of emotions so poorly understood in the dying embers of the Victorian preoccupation with the panoply of mourning ritual. This was the human need, when death of a loved one has been traumatic, to have recovery and identification of the body to establish certainty of death, knowledge of how it occurred, and a focus for grief. The process of recovery and identification of remains, developed for the first time in the Great War, has become a central part of official response to mass disaster, peaking in complexity in the last decade of the 20th century” (Hodgkinson 1). Yet the way Walter is memorialized still allows the violence, and the absurdity, to peek through the veil of stone.

And perhaps it’s a mere footnote for bookworms, but there’s even a strange literary dissonance between the poem posted across the street from the memorial, Ronald Leighton’s “Ploegsteert, 1915,” and Rupert Brooke’s far more famous sonnet “Peace:”

“Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping,

With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power,

To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping,

Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary,

Leave the sick hearts that honour could not move,

And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary,

And all the little emptiness of love!

Oh! we, who have known shame, we have found release there,

Where there’s no ill, no grief, but sleep has mending,

Naught broken save this body, lost but breath;

Nothing to shake the laughing heart’s long peace there

But only agony, and that has ending;

And the worst friend and enemy is but Death.”

-Rupert Brooke

Ploegsteert, 1915

“Love have I known and dawn and gold of day-time

And winds and songs and all the joys that are,

Known once, and as a child that tires of play-time

Leaped from them to the elemental dust of War.

I have seen blood and death, but all has ending

and even Horror is but made to cease.

I am sickened with love that only lives for lending,

and all the loathsome pettiness of peace.

Give me, good God of battles, a field of death,

a Hell of fire, a strong man’s agony . . ..”

-Ronald Leighton

Leighton’s poem was apparently drafted “shortly after” March 31, 1915. Brooke’s sonnet was published in 1915 but composed in the fall of 1914. Brooke died in April 1915 on a boat in the Aegean. Are the two poems simply rehearsing the same well-established rhetorical moves? Are they simply two instances of what oft was said in the first phase of the war? The shared features are strangely precise: the same “leaping” into war; same weariness or sickness with “loathsome” peace, and love’s “little emptiness”; same praise for the “God of battles,” same agony, same stoic refuge in that agony’s inevitable “ending.”

To stand in these fields 100 years later does at least change one thing: that verse, so beautifully constructed, sounds even more misguided and perverse than before. A collective madness must have taken hold in 1914, madness that allowed poets to write of “All the loathsome pettiness of peace” and “All the little emptiness of love.” Those are the things their broken bodies bought.

_________________________________

Magical dream of war’s end #2

It’s silent in this dream, but I know that the space is filled with deafening noise that I can’t hear. Everyone is suffering from it. But it’s less, it’s less every minute, and you can see the relief, involuntary, on their faces. We’re all soldiers working behind a line of artillery pieces. Huge guns. Smoking shell casings tumble out but no one replaces them. I see both the relief—because the noise has stopped— and confusion and fear on their faces. Because they can’t touch the shells. Even the fresh shells, stacked up in enormous piles behind us, seem too hot to touch, which doesn’t make any sense. At first they were panicking, because they have to keep firing, and then they tried gloves—but it’s no use. They show each other the welts on their hands, their forearms. Someone has welts on his brow from leaning close to a shell. They just can’t go near the things without blistering their arms . . . it seems to be getting worse. Another man runs in, tearing his rifle off his shoulder, and they’re all sharing the confusion. We run to the end of the line of guns, and soldiers everywhere are throwing away firearms, even ammunition belts. Looking across to the enemy lines, brows tight with fear, they register an equivalent silence. No shot has been fired for minutes now. My view expands and I can see up and down the lines, and across no man’s land. Every soldier has tossed away weapons and ammunition. No one can touch gunpowder in any form. Humans have acquired an incredibly violent allergy to the stuff. Instantly, and universally. It’s preposterous, but no one can argue with the reality of the effects, and groups of men are arguing, shouting, gesturing, some shrugging. The most resigned and practical soldiers have begun to brew tea, and await their new orders.

_________________________________

3. Battlefield cleaners

Revisiting these fields now, a century after the war began, is simply one more return in a long series of returns, of revisiting. My own visit just adds one more layer to the deep invisible sediment of viewing, reflection, and incomprehension. Yet as Stephen Graham asked long ago, “How is it possible to return to this place?” Is it more a matter of a place that was murdered, extinguished, with an entirely different space now occupying the old address?

Stephen Graham—soldier, journalist, travel writer and novelist—“revisited” Flanders in 1920, when the transition from battlefields to re-inhabited farms had just begun. Tenant farmers were living in shelters constructed of scrap materials, in the same fields where crews of “battlefield cleaners” gleaned any identifiable remains amid the shattered woodlots, the swampy rush-filled shell-holes, the fields radiant with flowers. Ypres remained a ruin encircled by bared wire.

Dead soldiers had of course been recovered, identified when possible, and buried throughout the fighting. Even then it had been a grisly task. Private J. McCauley described his own experience of the work in the fall of 1918: “Often have I picked up the remains of a fine brave man on a shovel. Just a little heap of bones and maggots to be carried to the common burial place. Numerous bodies were found lying submerged in the water in shell holes and mine craters; bodies that seemed quite whole, but which became like huge masses of white, slimy chalk when we handled them. I shuddered as my hands, covered in soft flesh and slime, moved about in search of the disc, and I have had to pull bodies to pieces in order that they should not be buried unknown. It was very painful to have to bury the unknown” (J. McCauley, IWM DOCS 97/10/1, cited in Hodgkinson).

When Graham met battlefield cleaners in 1920, they were still struggling with the same need to make known those soldiers still unknown, to overcome one kind of revulsion in order to conquer another—the unthinkability of all the nameless, placeless, dead. At the site of one of the war’s early battles, near Zandwoorde, he speaks to “exhumers . . . patiently seeking the dead who were left behind—the old dead of that first battle” (Graham 29). One of these exhumers tells Graham that they “[b]rought in about thirty Borders yesterday.” (The site lies only a few kilometres northeast of today’s Ploegsteert memorial, where Walter Orchard of the Border Regiment is commemorated).

Graham asks the exhumer, “Do you sleep out here on this battlefield?” The man replies:

“We bin ‘ere six months now.”

“No ghosts?”

The man smiled. He saw none. He felt the presence of none. Imagination did not pull his heart-strings. If it did, he would go mad” (Graham 30).

In 2014, walking and slowly cycling through Flanders, that dangerous imagination has become a necessity. I’ve been warned all my life, each November, against forgetting. But there are so many kinds of remembering. Without imagination, without finding ways to make the fields under my feet my own, and ways to hear a century’s accumulation of words with fresh ears, how can I make any connection at all, today, with this place?

_________________________________

Magical dream of war’s end #3

Where did they all come from? None of us heard anything, saw anything. And yet we barely sleep in the trenches, coughing in the damp, always vigilant, tired nerves strung too tight for proper rest. How did hundreds of women slip past us? Most are dressed as nurses, but no soldier would be deceived. Their bodies still register surprise at what they see here: a shoulder tightens, a head turns away from one horror or another. Things we no longer see. A real nurse with even one week’s experience would not flinch as these do. But what the hell can they be doing here? It’s a colossal error and we’ll be the ones to pay for it, if they even live. And what are they up to now? In the dark, skirts bunched up, they’re helping each other over the parapets . . . it’s madness, but I can’t seem to get up to stop them. I’m immobilized by dread, by confusion. Women in the trench . . . they’ve started walking . . . there’s just enough light to fire, and so it starts. One falls, then another. I hear a scream, the sound of rage more than fear. They’ve stopped, and so has the firing, which never really developed. They’re standing there in the grey light, they’re singing something, and there’s no firing at all. Absolutely no one has the slightest bloody clue what to do. There’ll be no fighting in these conditions, I can tell you that right now.

_________________________________

References:

Beckett, Samuel. Watt. New York: Grove, 2009.

Graham, Stephen. The Challenge of the Dead: an impression of the battlefields of France and Flanders just after the war. London: Ernest Benn Ltd, 1930. (First published 1921.)

Gurney, Ivor. “To His Love.” http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/248276.

Hodgkinson, Peter E. “Clearing the Dead.” http://www.vlib.us/wwi/resources/clearingthedead.html.

Mew, Charlotte, “May 1915.” The Rambling Sailor (London: Poetry Bookshop,1929).

“Ploegsteert Memorial.” Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Cemetery Details

http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/88800/PLOEGSTEERT%20MEMORIAL

Pound, Ezra. “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley [Part I].” http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174181.

Brooke, Rupert. “1914 I. Peace.” https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/html/1807/4350/poem226.html.

Leighton, Roland. “Ploegsteert, May 1915.” http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/collections/item/5614.

Bio: Dianne Bos

Dianne Bos was born in Hamilton, Ontario, received her B.F.A. from Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, and currently divides her time between the foothills of the Rockies and the Pyrenees.

Her photographs have been exhibited internationally in numerous group and solo exhibitions since 1981. Recent important national exhibitions of Dianne’s work include: ‘Light Echo’, an innovative installation at the McMaster Museum of Art, in collaboration with Astronomer Doug Welch, which linked celestial and earthly history; It’s You!: Unexpected Photographs from Papua New Guinea, at the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Art Gallery, PEI., and Reading Room at the Cambridge Galleries an exhibition exploring the book as a camera. Her work is currently part of the exhibition Poetics of Light, Contemporary Pinhole Photography, at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History, New Mexico. Bos’ public art commissions include a large light box installation at Toronto’s VU condominiums entitled ‘Palimpsest’ and the banner design for the city of Calgary’s bridges. Upcoming exhibitions at the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery will include ‘See Attached’ a photographic dialogue with photographer Sarah Fuller and ‘The Sleeping Green: No Man’s Land 100 years later’, unique images inspired by WW1 Canadian battlefields.

Many of Bos’s recent exhibitions feature handmade cameras, walk-in light installations, and sound pieces. These tools and devices formulate and extend her investigations of journeying, time, and the science of light.

“I’m fascinated by the history of photography and the science of light and how different devices change our perception of time and space,” says Bos. “My work challenges the view of photography as a way to “capture an instant in time. Viewers have said that my work evokes the memory-image that remains for them long after they have viewed a familiar location. I think this recognizes the importance I have always assigned to time, memory, and capturing the essence of the place, in my images of architectural icons and classic travelers’ destinations.”

Dianne Bos is represented by Newzones Gallery of Contemporary Art in Calgary. Kostuik Gallery in Vancouver and Beaux Arts de Amerique in Montreal.

For more information visit: www.diannebos.ca

Bio: Harry Vandervlist

Harry Vandervlist teaches in the English department at the University of Calgary. He has published scholarly work on modernism, especially Samuel Beckett’s early fiction, and on Canadian literature. In 2000 he edited the the collected poems of Banff poet Jon Whyte. He has been the director of the undergraduate program in English, and has published reviews, author interviews and magazine pieces in Quill and Quire, AlbertaViews, Avenue, Swerve, The Calgary Herald and FastForward Weekly. In the fall of 2016 he will lead a University of Calgary travel study course on World War One writing, which will visit London’s Imperial War Museum and Canadian sites in Flanders.