In taking advantage of the opportunity to peruse the University of Lethbridge’s impressive art collection, I was drawn to Isabelle Hayeur’s Refuge and Allyson Clay’s A Constant Longing because both works speak to issues of landscape and identity – broad concepts which I, and many other students of Canadian visual culture, am compelled to confront. Beyond simply throwing a traditionally “Canadian” pastoral landscape out the  proverbial window, both works raise more questions about the relationships between landscape, familiarity and identity than they answer. Each work evokes a landscape that is simultaneously stunning yet hostile, thus raising questions about the validity of a perceived connection to space, while suggesting a more pluralistic definition of an “ideal” or “familiar” landscape.

proverbial window, both works raise more questions about the relationships between landscape, familiarity and identity than they answer. Each work evokes a landscape that is simultaneously stunning yet hostile, thus raising questions about the validity of a perceived connection to space, while suggesting a more pluralistic definition of an “ideal” or “familiar” landscape.

A deep attachment to landscape has long been considered a fundamental tenet of Canadian nationalism. The canonical reinforcement of painters such as the Group of Seven has played a significant role in encouraging this intersection between identity and place as a means of a broader articulation of an idealized national identity. As Anne Whitelaw asserts in “Whiffs of Balsam, Pine and Spruce,” “it is this legacy of the Group of Seven, their preoccupation with the landscape as artistic subject matter and as a philosophy of Canadian distinctness, that has provided coherent material around which a narrative of national identity has been articulated.”[1] However, as Josephine Mills suggests in Land Matters, by the later decades of the twentieth century, a variety of artists began to critique and revise this traditional nationalist fiction.[2] In Souvenirs of the Self, for example, through situating herself as a tourist in the iconic Banff landscape, Jin-Me Yoon deftly questions the validity of a nationalistic attachment to landscape and its implications on her own identity. Isabelle Hayeur’s and Allyson Clay’s works, albeit through highly disparate means, transcend this initial critique by shifting notions of the landscape “ideal,” while simultaneously questioning the validity of a human connection to landscape by implicating us in its transience and decay.

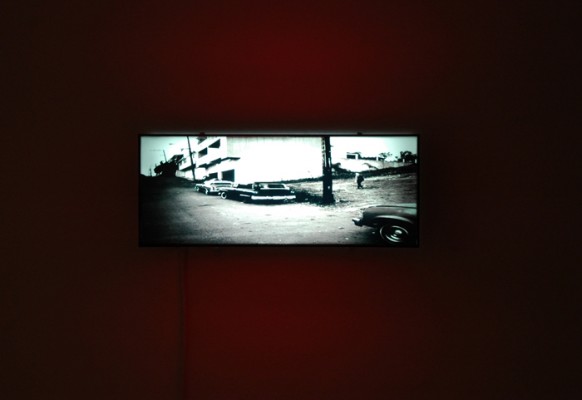

Allyson Clay’s A Constant Longing is a relatively small, rectangular light-box. Translucent red panels frame a main panel featuring a horizontally stretched photograph of a desolate urban area. The small size and three dimensionality of A Constant Longing forces the viewer to sidle around the work, craning his or her neck and back to view all of the panels – creating discomfort but also a sense of intimacy. This feeling of intimacy is amplified by the glow emanating from within the light-box – the work itself is undeniably stunning. The centre panel’s photograph depicts a street lined with concrete apartment blocks, stark street lights and cars. The urban scene is devoid of any signifiers or implications of geographic specificity – this could be a street in anyone’s hometown, and it is likely far closer to the experiences of many living in Canada than a painting of Georgian Bay by the likes of Tom Thomson or A.Y. Jackson. However despite this sense of familiarity, the urban landscape depicted in the centre panel simultaneously imparts a feeling of discomfort. The horizontal distortion of the image skews the perspective and creates a sense of movement, provoking an almost physical unease. The buildings, cars and lone individual dotting the image, however familiar, are unfriendly – a discomfort that exists in contradiction with the sense of contemplative intimacy fostered by the smallness of the work itself and the warmth from the light within.

the likes of Tom Thomson or A.Y. Jackson. However despite this sense of familiarity, the urban landscape depicted in the centre panel simultaneously imparts a feeling of discomfort. The horizontal distortion of the image skews the perspective and creates a sense of movement, provoking an almost physical unease. The buildings, cars and lone individual dotting the image, however familiar, are unfriendly – a discomfort that exists in contradiction with the sense of contemplative intimacy fostered by the smallness of the work itself and the warmth from the light within.

Through highly disparate means, Isabelle Hayeur’s Refuge provokes a similarly conflicted experience. A massive photographic print, Refuge also depicts a beautiful yet decaying urban landscape. An overcast but luminescent sky initially draws the viewer’s eye to a pseudo-pastoral city greenbelt which is foregrounded by a decaying brick and steel archway. Bricks, garbage and other debris litter the immediate centre-front of the image. Despite being part of the same environment, the greenbelt and the decaying structure seem at once harmonious and at odds – as if one is decaying to allow space for the other. Interestingly, much of Hayeur’s other work involves the fusing of two disparate images to create composite images that are both seamless and unsettling. While Refuge is not one of these composites, Jan Allen’s analysis of their impact is highly apt: “Despite the visual harmonies within these compositions, the elision of seams is experienced as a form of interference. Hayeur sets up a situation in which she, like Robert Smithson, raises the fundamental question of how we experience and occupy the land.”[3] The deteriorating brick structure, punctuated by a discarded fast food cup in the lower left corner, highlights the transience of human presence on the landscape and in doing so questions what it means, or whether it is even possible, to inhabit or truly connect and identify with a place. But as is the case with Clay’s A Constant Longing, Hayeur’s Refuge is aesthetically beautiful and stunningly composed. And as the work’s title suggests, the brick and steel structure feels oddly comforting and familial as it envelopes the viewer’s outward sight lines.

Both Isabelle Hayeur’s Refuge and Allyson Clay’s A Constant Longing foster a paradoxical viewing experience. The works are simultaneously familiar and hostile, expressing ambivalence towards an occupation of, or identification with, a particular landscape and they remove us distinctly and evocatively from the canonical landscape form.

– Elizabeth Diggon

Works Cited:

Allen, Jan. “Self-Destroying Postcard Worlds: The Synthetic Landscapes of Isabelle Hayeur.” Prefix Photo 12 (2005): 16-24.

Mills, Josephine. “Land Matters.” In Land Matters, 9-12. Lethbridge: University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, 2008.

Whitelaw, Anne. “Whiffs of Balsam, Pine and Spruce.” In Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity and Contemporary Art, edited by John O’Brian and Peter White, 175-179. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007.

[1] Anne Whitelaw, “Whiffs of Balsam, Pine and Spruce,” in Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art, ed. John O’Brian, Peter White (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), 176

[2] Josephine Mills, “Land Matters,” in Land Matters, ed. Josephine Mills (Lethbridge: University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, 2008), 9

[3] Jan Allen, “Self-Destroying Postcard Worlds: The Synthetic Landscapes of Isabelle Hayeur,” Prefix Photo 12 6.2 (2005), 20

38 thoughts on “Revising the Canonical Landscape Form”