Helen Christou Gallery

A Glimpse into Chinatown

January 21 – June 24, 2022

Introduction:

The University of Lethbridge Art Gallery is pleased to present this new exhibition by Lethbridge-based artist Angeline Simon. We commissioned the artwork as part of a mentorship in social practice with Alana Bartol, associated with her project Processes of Remediation: art, relationships, nature that culminated in an exhibition in the Hess gallery in 2010. The structure of the mentorship had to change drastically due to restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Creating the relationship between Simon and Bartol took on added importance during the isolation and emotional pressure of lockdowns and lack of in-person contact.

Simon was already showing exceptional promise when she was a student at the University of Lethbridge. The rare combination of her thoughtful approach to social issues and technical skill caught my attention. Since graduating in 2018, she has continued to explore connections between historical and contemporary ideas by juxtaposing archival images with her own recent photographs.

Working with Alana Bartol as a mentor, Simon was able to take on a major new project in which she addresses anti-Asian racism in Lethbridge through her haunting images of the architecture of the former Chinatown along with archival texts and objects. Simon’s beautiful, poetic images and personal approach in A Glimpse into Chinatown creates a compelling connection for viewers to the ongoing legacy of race relations in our region.

Josephine Mills

Director/Curator

Artist Statement:

When I moved to Lethbridge in 2003 with my Chinese-Malaysian mother, we would shop at the Asian Supermarket and Bow On Tong to purchase specialty food and household items that weren’t easily found at other stores. Although Chinatown only had one store for my mother to shop at, it provided her with the opportunity to meet other Chinese folks such as Albert Leong in a small city where she didn’t have many Chinese friends. Bow On Tong was a little slice of home for my mother; a place where she felt familiarity.

Alongside the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen rising anti-Asian racism and xenophobia in western countries prompting many cities to protest against Asian hate. In the absence of a Lethbridge rally to protest this violence, I turned my curiosity to the beginnings of Lethbridge’s Chinese history. With the help of the Galt Museum and Archives, Albert Leong – previous owner of Bow On Tong, Belinda Crowson of the Lethbridge Historical Society and archived newspaper articles, I began collecting photographs and stories that offered a glimpse into Chinatown.

Bow on Tong and Kwong on Lung (316 and 318 2 Ave South) are two buildings central to this exhibition that were owned by Albert and his family from 1926 until 2021. Both buildings have been designated as provincial historic resources as they played a vital role in Lethbridge’s formative years. These two buildings served the early Chinese residents of Lethbridge with a grocery store, restaurant, Chinese herbal medicine shop and a boarding house. What was once a bustling block of Chinese businesses has now died down to an almost empty quiet street.

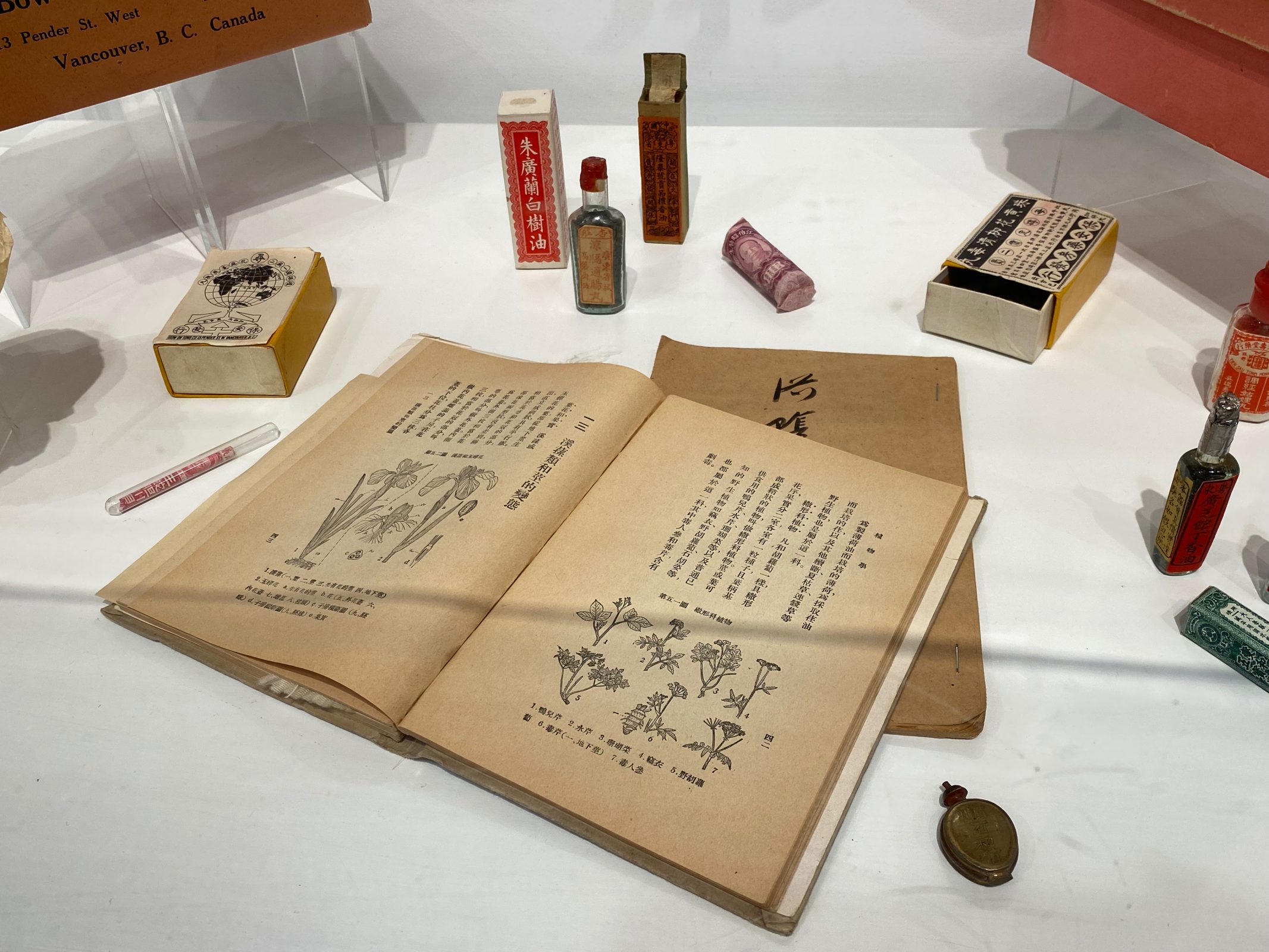

Due to structural instability, Albert’s buildings were condemned in 2013. Efforts by multiple groups and organizations had been made to try and save Bow On Tong and Kwong on Lung – but to no avail as they could not raise enough money. In the spring of 2021, both buildings were put up for sale. Not knowing what would happen to them, I was able to document both interiors in hopes of preserving some memories of the spaces. Albert Leong, described as “the last man in Chinatown” was born in the basement of Bow On Tong and graciously gave me a variety of small medicine bottles that date back to the days when his father Way Leong sold Chinese herbal medicine (1926-1960s). Although Albert never learned Chinese medicinal practices, he held onto these artifacts and curiosities, giving tours to school groups and sharing Chinatown’s history to anyone who would lend an ear. These photographs and objects formed the basis of this exhibition, allowing me to piece together moments of Chinatown’s past and present that I was searching for.

Digging through the digital archives of the Lethbridge Herald, I found articles on the 1907 Christmas Riot and Bylaw 83, two of which are included in this exhibition. Both events had an impact on our Chinese community, and shaped the development and locations of Chinese owned businesses. The third newspaper article is from The New York Times archives, reminding me that Lethbridge tends to only make international headlines when a terrible occurrence takes place. I sourced two political cartoons in this exhibition from the BC Saturday Sunset newspaper to paint a picture of the political climate of Western Canada in the early 1900’s. Between the cartoons is a Certificate of Chinese Immigration, on loan from the collection of the Galt Museum and Archives – a remnant of the head-tax imposed on all Chinese immigrants from 1885-1923, a period of almost 40 years.

With permission from the Galt Museum Archives, I scanned photographs of Chinatown from their collection to incorporate into my work. Merging these archival images with my own photographs of Chinatown asks viewers to consider the many lives and stories that have touched these places. These buildings may seem like empty ruins today, but previously, they were a place of refuge. Chinatown could provide sanctuary, comfort and familiarity for a marginal community in times of prejudice and hardship. Although much time has passed, this sleepy row of buildings on 2nd Avenue South were once intimate spaces so important to a marginal Chinese community and deserve to be celebrated and remembered as a fundamental part of our city.

Angeline Simon

An Essay by Alana Bartol:

More than a Glimpse: Looking with Care at Chinatown in Lethbridge

To question how spaces came to be, and to trace what they produce, as well as what produces them, is to unsettle familiar everyday notions. -Sherene Razack

Angeline Simon’s A Glimpse into Chinatown is currently in the Helen Christou Gallery, the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery’s satellite exhibition space, part of the main pedestrian route at the intersection of the Centre for the Arts and the University Library. Entering the hallway gallery, one is met with a series of artworks that cleverly merge past and present, drawing viewers into Lethbridge’s Chinatown through photography, archival articles, images, and documents, as well as objects from the Bow On Tong, one of the last remaining historic buildings in Chinatown.

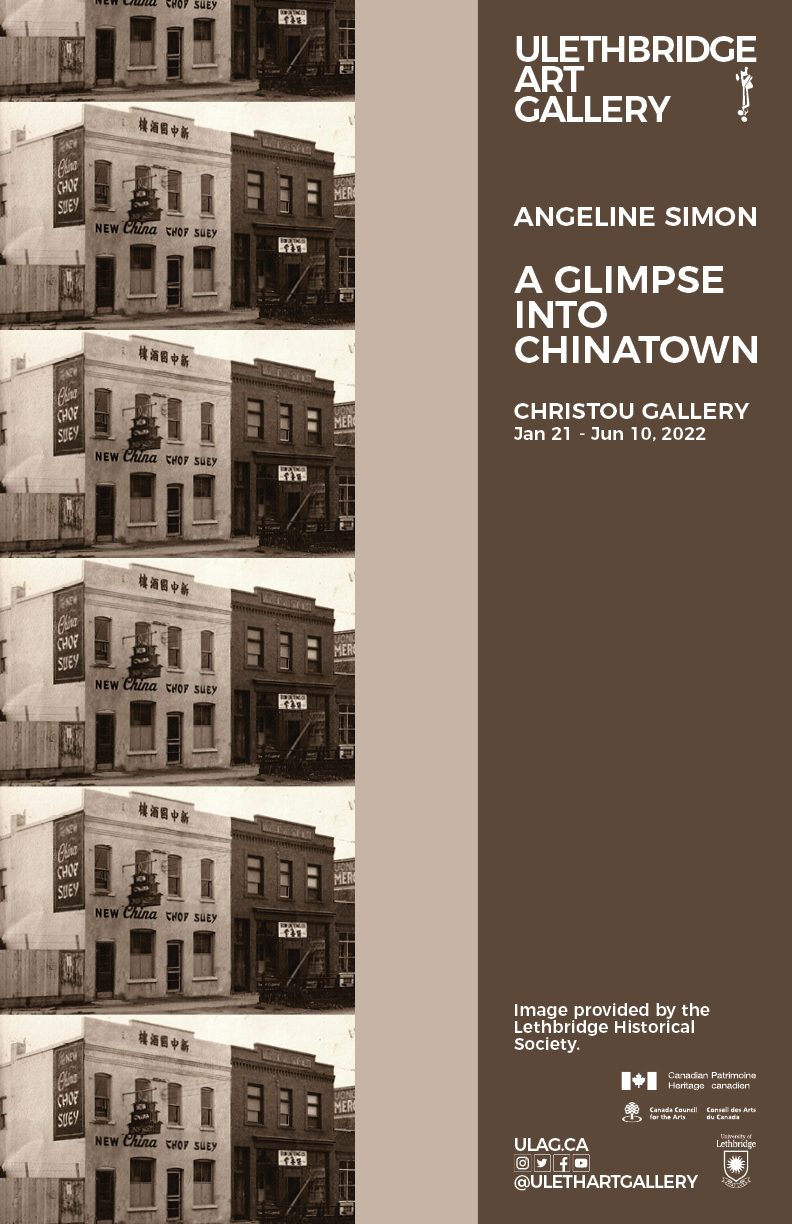

At the southwest end of the hall is a floor-to-ceiling mural of an historical photograph of the Kwong On Lung (also known as Wing Wah Chong Co.) and Bow On Tong buildings, two buildings that have come to represent Lethbridge’s historic Chinese neighbourhood. One of Alberta’s oldest Chinatowns, it once spanned a nine-block area. Despite being designated historic buildings by the City of Lethbridge and the Province of Alberta, the buildings were sold in 2021, while Simon was developing this body of work. Wheat-pasted directly on the wall, the sepia-toned photograph sourced from the Lethbridge Historical Society has a nostalgic air, recalling museum displays of another time. Framed by two columns with staircases on either side, passersby become implicated in the story of Chinatown as they move through the corridors as if walking by these buildings on the street. This is not a story of a past long gone, but one that lives on in the present.

A form of street art, wheat-pasting is a direct action and type of intervention into public space. It can disrupt the everyday and reach audiences in the wider public sphere. By claiming space for Lethbridge’s Chinatown directly on the hallway walls, Simon brings what is vanishing into view, drawing parallels between the interstitial space of the corridor and the development and decline of Chinatown.

Since COVID-19, there has been a marked rise in Anti-Asian racism, violence, and discrimination against Chinese Canadians. Members of the Asian community and their allies have held protests across what is colonially called Canada, including in Amiskwaciy-Wâskahikan (Edmonton) and Mohkínstsis (Calgary), to raise awareness and call for action. Calls that might be unheard of in a province where earlier this year Premier Jason Kenney made racist anti-Asian comments during an interview. In her artist statement, Simon notes that the absence of such protests in Lethbridge compelled her to look deeper into the Chinese community where she has lived for almost 20 years.

Though places of culture, safety, and community, Chinatowns can also be viewed as the result of racist laws that underpin the myths of white settler Canadian society, restricting the movement, settlement, and livelihoods of Chinese people. Catherine Chow writes, “Chinatown’s landscape has a dual personality as space constructed by Chinese Canadians for themselves and as a social construct of Chineseness for and by a white settler society” (11). Simon’s careful curation of articles, images, and artifacts reminds us that the people who created Chinatowns and found safety within them did and do so as an act of resistance in the face of violence, racism, and exclusion.

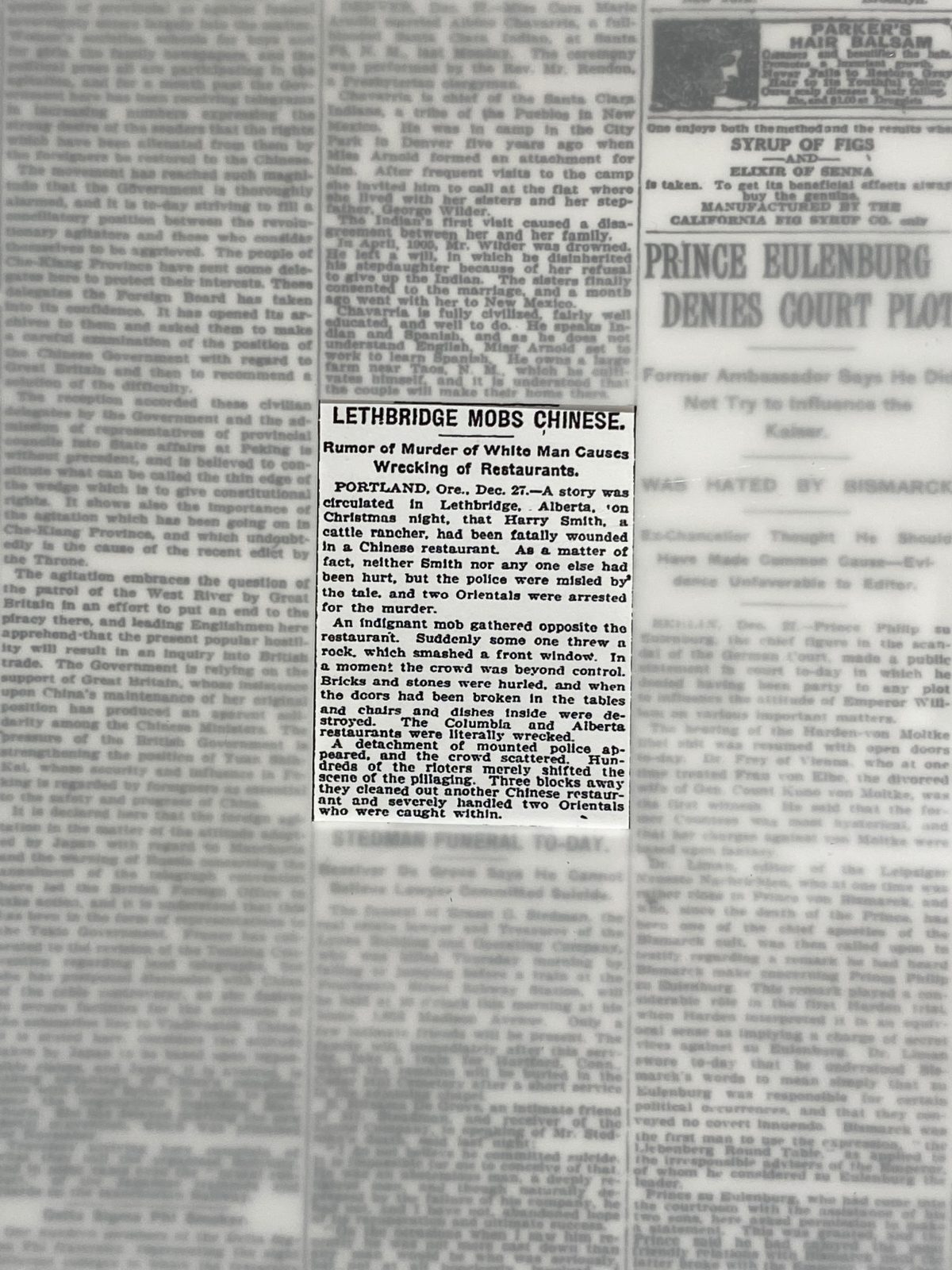

In the centre of the hallway below the exhibition title sits a framed Chinese Head Tax certificate entitled Certificate of Chinese Immigration – Jung Sew Soon, on loan from the Galt Archives. Surrounding it are two 1907 editorial cartoons from BC Saturday Sunset that demonstrate support for the Chinese Head Tax, a racist tool of Canada’s exclusionary immigration policies. Newspaper articles from the Lethbridge Herald (1908, 1910) and New York Times (1907), draw attention to the violence and exclusion of Chinese people in Lethbridge. “Area for Chinese Laundries Defined” gives an account of Bylaw 83, which restricted Chinese laundries to the “Segregated Area” later known as Chinatown.

Two articles, “Lethbridge Mobs Chinese” and “Vented Wrath on Chinamen”, report the Christmas Riot of 1907, detailing whitewashed stories of a racist white mob that violently attacked Chinese businesses and people in Lethbridge based on a false rumour that a white man had been murdered. The race riot garnered international coverage. Each full newspaper page is overlaid with frosted mylar, obscuring but not concealing what lies beneath. Cut-outs in the mylar direct the viewer’s attention to the articles, compelling audiences to read while drawing attention to the ways in which history is framed and presented. How easy is it to overlook these aspects of the City’s past and how they impact the present in explicit and less obvious ways?

I was Angeline’s mentor during the creation of A Glimpse Into Chinatown as part of “Processes of Remediation: art, relationships, nature”, a project with the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery. Throughout the mentorship, we had conversations about the desire to work with and in community, and the difficulties of doing so during the pandemic. We talked about the history and present state of Lethbridge’s Chinatown, the complications of archival research, the difficulty of finding documentation and information about Chinatown and its residents, and the possibility of conjuring awareness and history when gaps and questions remain.

During a letter exchange, Angeline sent me a collection of small printouts of her recent work. In her letter, she expressed the urgency she felt to address “the constant thought of being biracial” in her work. A second-generation Canadian of Chinese-Malaysian and German ancestry, Simon often draws on her family photographic archive as material, scanning, digitally manipulating, cutting, and collaging the images, resulting in artworks that bridge temporal, geographic, cultural, and ancestral connections.

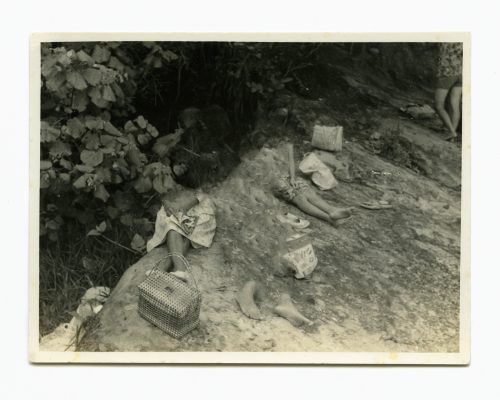

In the collection of mailed images, some photographs are clearly more recent, full-colour snapshots of the artist traveling, while others are older black-and-white photographs of family members including the artist’s mother and aunt, taken in the mid-20th century. Simon’s digital manipulations have a disarming and sometimes humourous effect. In Hannah at Yoho National Park, a figure, presumably, Hannah, appears to be canoeing straight into a white and grey chequered digital pattern. With the landscape removed, one can imagine a picturesque landscape or leave Hannah paddling in a virtual void. Users of Photoshop will be familiar with the chequered background; it is the image editing software’s method of rendering transparency, a way to see the effect of the removal of the background. I am reminded that in real life, removal is often all too easy to overlook.

In other images, Simon employs the content-aware function of Photoshop to similarly draw attention to absence. Swee Cheng II (2020) and Swee Choo at School (2020) are haunting images. The figures appear ghostly, like an echo of themselves. Using Photoshop’s content-aware function, erasure becomes additive as the removed parts are filled in with data from the surrounding areas. The effect is strange and disconcerting as identifiable features, faces, and sometimes whole bodies disappear. A pair of hands or feet remain the only indicator of a person’s presence. The white borders and edges of each photograph are visible, a reminder that it is a physical, tactile object. These images hold my attention, asking for slow, considered looking. In searching for what’s missing, I become attuned to the processes of manipulation of information and images and the role photography plays in the construction of memory whether it be familial, communal, or individual.

Simon’s work on Lethbridge’s Chinatown is timely not only in a local context, but also across the province and country, as many artists and curators examine, honour, and contribute to broader conversations about Chinatowns across so-called Canada. Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections (2021), curated by Karen Tam for Griffin Art Projects (Vancouver), an exhibition that presents over 159 pieces by 29 artists, seeks to examine “how narratives are constructed around the idea of Chinatown and the colonial notions that underwrite some of these relations” (Tam, 2021). Drawing on public, familial, and private archives, many of the works illustrate the ways in which Chinatowns can be recognized, valued, and sustained as centres of communities.

Photographs of Chinatowns often present the architecture, focusing on street views and building exteriors. Curator Karen Tam speaks about the dangers of focusing only on the outer views of Chinatowns, particularly depictions by non-Chinese people, that exotify Chinatown “…and at times that can be quite problematic, basically just showing the exterior and that it’s an exotic locale” (42:10-42:31). Tam’s approach contrasts these depictions with photographs by artists like Jim Wong-Chu who were involved with the Chinese communities they documented. Tam also points to the lack of documentation by the residents themselves, “It shouldn’t be surprising, but it is surprising, to find that there’s not a lot of materials [of] early depictions of Chinatowns and Chinese residents and that there were hardly any by Chinese Canadians” (34:47-44:11). She goes on to say that it is out there and that the work of finding it “needs to be done.”

Simon is one of the many artists taking up this work. Simons’ series of photomontages reveal complexity and depth behind the exterior, merging older and newer images, and ones that capture residents behind the walls. Black-and-white historical photographs from the Galt Museum and Archives of some of the Chinatown residents merged with full-colour photographs that Simon has taken of the interiors and exteriors of two of the remaining buildings of Chinatown. In this elegiac series, images from the past unsettle the cultural erasure of the present, humanizing a community whose destruction has been taken for granted and overlooked.

Simon’s series of photomontages, each without an individual title, collapse past and present, bringing the same reflective quality to the work that she does when working with her family photographs. Instead of employing techniques of erasure, she presents the people that worked, lived, and frequented these spaces in full view. Facial expressions, gestures, and body language bring emotional resonance to moments of everyday life. As the title foreshadows, the audience can get a ‘glimpse’ of the people who built, lived, gathered, sustained, and breathed life into these vital community spaces.

One of the photomontages includes a photograph Simon took from the inside of the main floor of the Bow On Tong. The space is largely empty with signs of packing up and moving all around: boxes, plastic bins, a dolly. Boards and plastic cover windows. The interior lights are off. Natural light makes its way in through the storefront windows that remain uncovered. The present-day image is layered with a historical black-and-white photograph of the same space with a man measuring out medicine on a scale. His eyes downcast, he concentrates on the task at hand. Boxes, bottles, and vases labelled with Chinese characters are in the foreground and line the shelves in the background. Some of the edges of the photograph are visible, along with its accession number.

From the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery collection, Simon includes Chinese National League Building, August 1998 (The Lethbridge Project) in the exhibition, a photograph by renowned Canadian photographer Geoffrey James. Once a community space that provided Chinese language and education, as well as access to the arts, games, and meetings, the Kuo Min Tang or Chinese National League Building is now remembered in photographs. The two-storey rectangular brick demolished in 2011, exhibited a western flat, plain, and austere façade. The black-and-white photograph captures its stark presence appearing in sharp relief and frozen in time.

Shown alongside the photographs, in a museum vitrine, is a collection of objects from the Bow On Tong gifted to the artist by Albert Leong. Leong’s family established Bow On Tong and Kwong On Lung almost 100 years ago. The building served many functions for the community over the years, including an apothecary, Chinese goods store, lodging, and home to the Leong family. The items that came from the apothecary are now artifacts on display. The book is open to pages with Chinese characters and an illustration of a plant displayed alongside Chinese herbal medicines in bottles and boxes of their original packaging. One of the packages has been opened, a cracked wax ball partially revealing its contents. As Simon explains in her statement, Albert’s father sold Chinese medicine. In conversation, Angeline said she felt a responsibility to portray the history and these stories, to give back to the community that she is part of. In her hands, this medicine becomes art that makes space for histories, care, and processes of healing.

Alana Bartol

Works Cited

Chow, Catherine. Chinatown geographies and the politics of race, space and the law. 2007. University of British Columbia. LLM Dissertation. Allard Research Commons, https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/theses/381.

“Curator’s Tour with Karen Tam.” YouTube, uploaded by Griffin Art Projects, 17 February 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mv6D5f7l88U&ab_channel=GriffinArtProjects

Razack, Sherene H. “When Place Becomes Race.” Race, Space, and the Law: Unmapping a White Settler Society, edited by Sherene Razack, Between the Lines, 2002, 1-20.

Simon, Angeline. “Artist Statement – A Glimpse into Chinatown.” University of Lethbridge Helen Christou Gallery, 2022.

Simon, Angeline. Letter to Alana Bartol. 2020.

Tam, Karen. “Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections.” Griffin Art Projects, 2021, https://www.griffinartprojects.ca/exhibitions/whose-chinatown/. Accessed 3 May 2022.