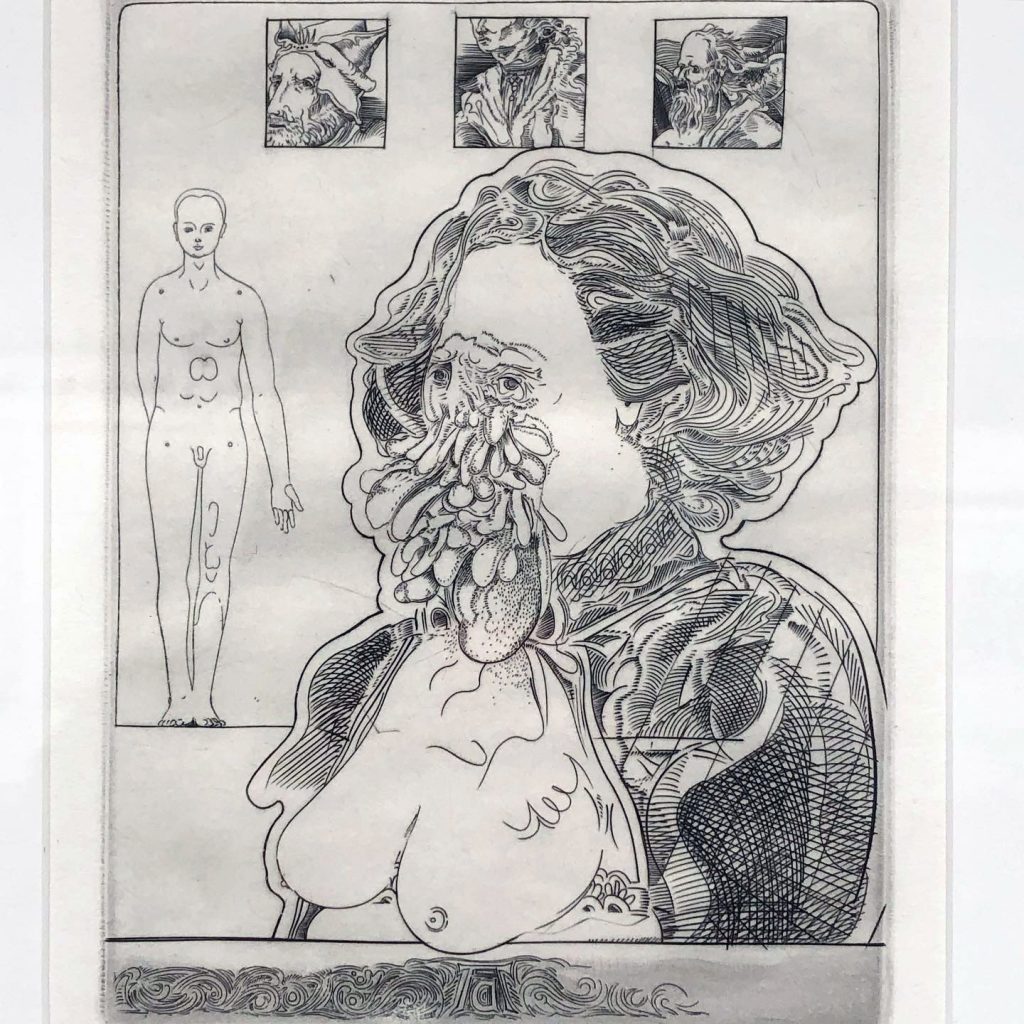

In this online project, I hope to “walk” you through my exhibition currently up at the Helen Christou gallery since part of social distancing is to #stayhome, starting with this vignette. Pairing John Will’s print, “Durer’s Dream” with my work, “resolvere” was to think about expulsion versus release. While the male bodies present in “Durer’s Dream” are treated with medical impartiality, it doesn’t take an expert to look at the treatment of the woman’s body and see the extremity of difference. She expels grotesque from her face; her breasts from her garment — for me, the disdain for the subject is prominent in the details; perhaps she said something the artist disliked.

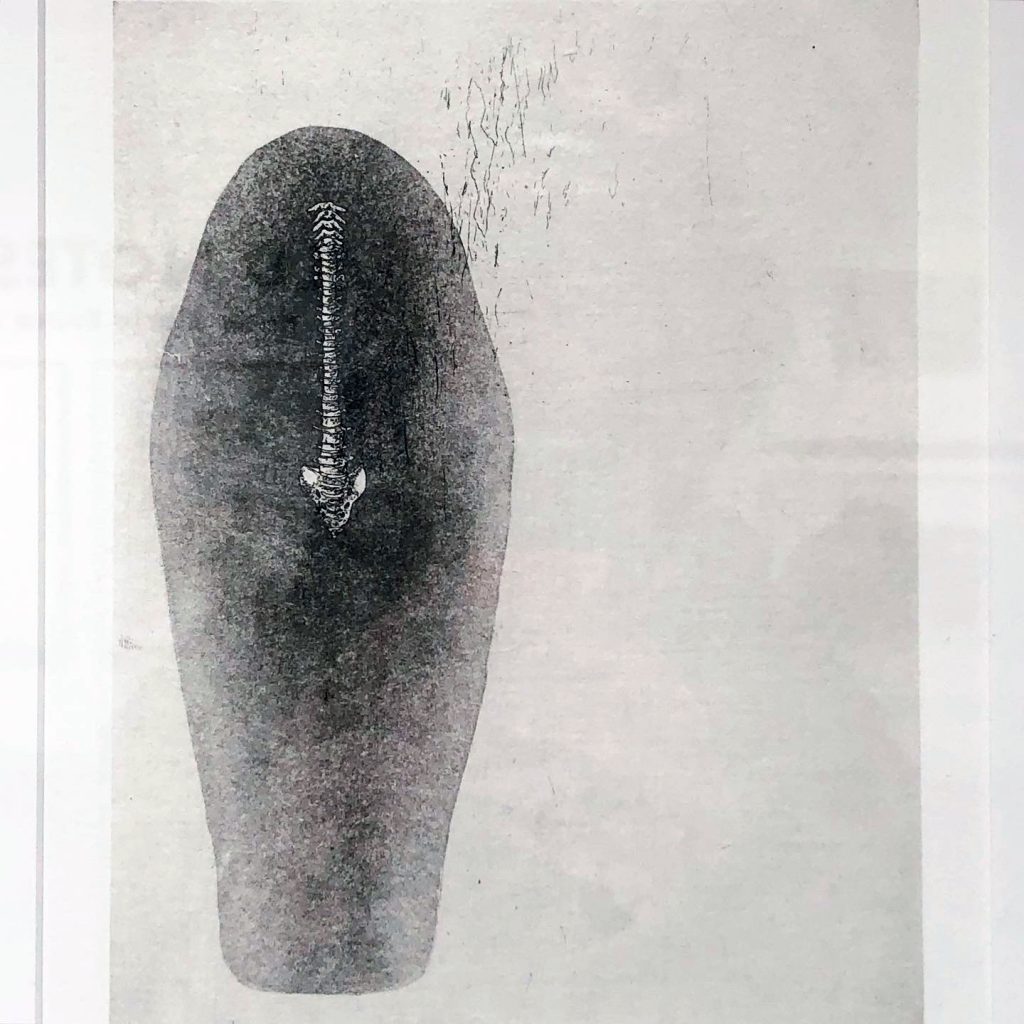

“resolvere” came about after a conversation with an acupuncturist, in which we identified that I was holding fear practically everywhere in my body (apologizing for being) and it was preventing me from communicating. Before she left me with pins everywhere, she told me to breathe through my fear and release it from my spine. Finding my backbone again — carrying those words — continues to be an ongoing process. But that initial release was powerful and allowed so much of my inner thoughts, out. Expulsion versus release becomes an interrogation of perspective — a running thread throughout this exhibition.

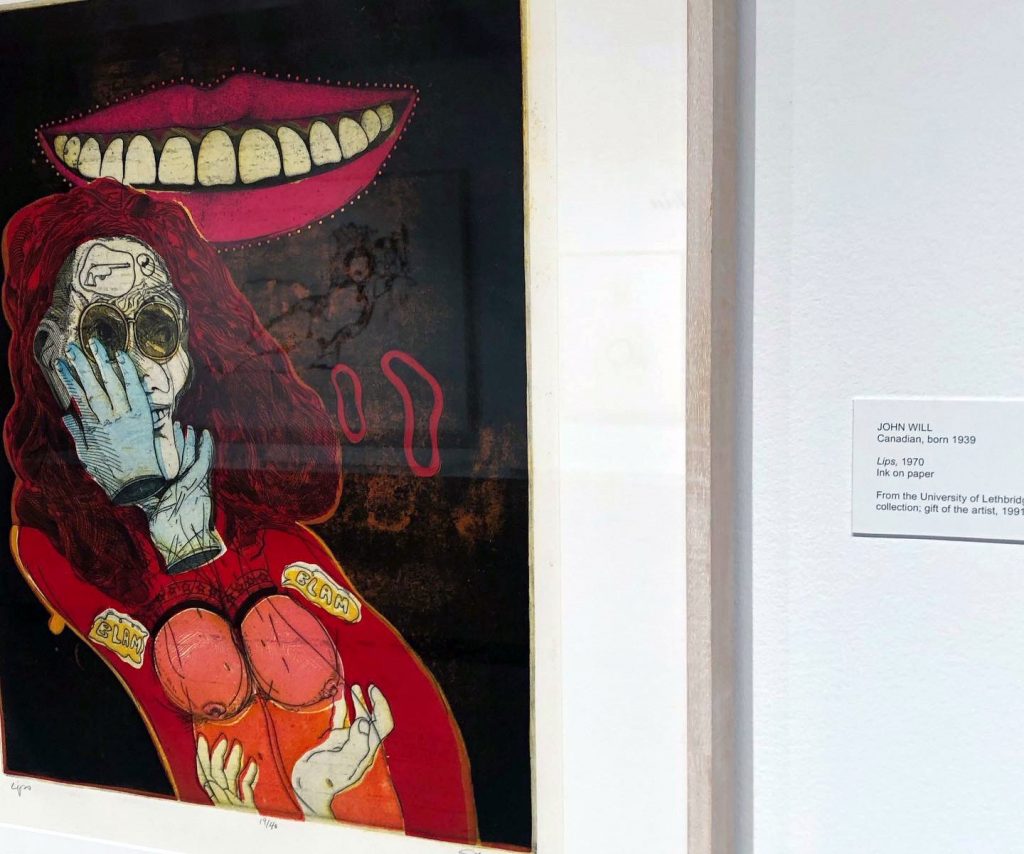

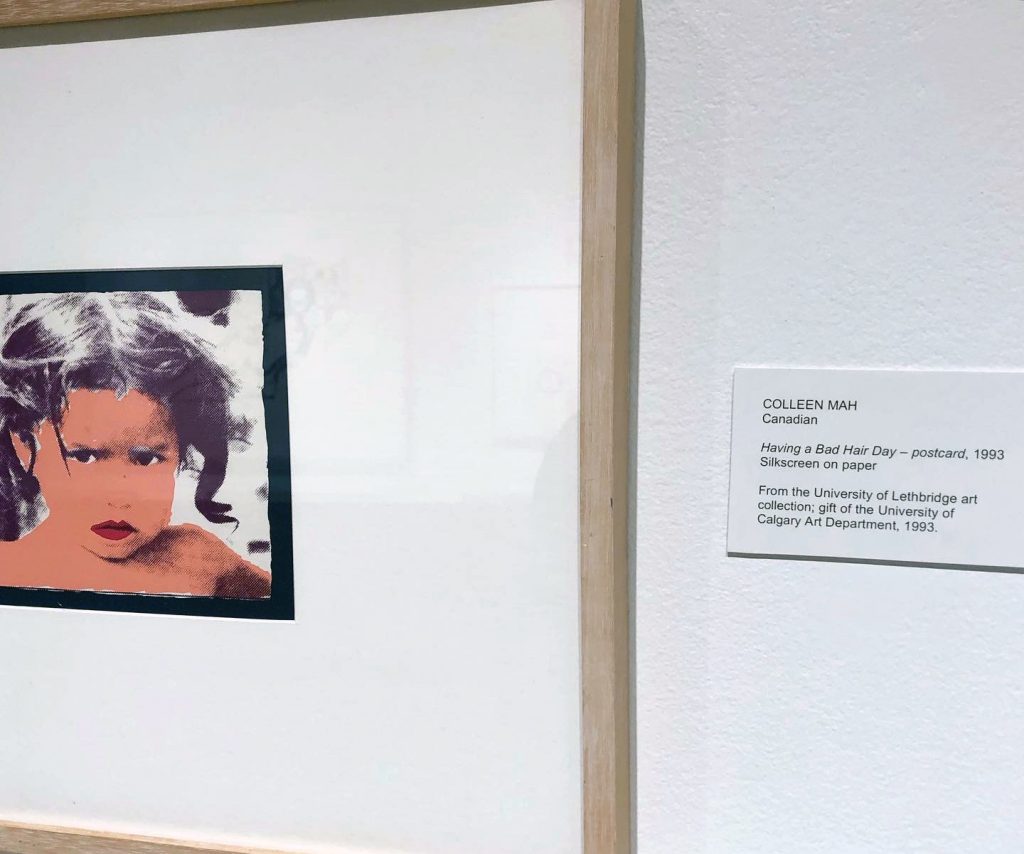

This next slice of the exhibition I jokingly refer to as the “nips and lips” section. While none of my pieces are present here, I used Colleen Mah’s “Having a Bad Hair Day” as a stand in — by placing her work between the prints “Lips” by John Will and Tom Wesselmann’s “Nude (for Sedfre)” I hope to draw attention to the ridiculous nature of these two depictions of women, the little girl’s expression denoting a certain kind of disdain.

“Nude (for Sedfre)” offers the viewer a passive body with no way to defend herself: she has no hands to push away with, no legs to get up and leave, and no eyes to communicate with. This last part feels particularly defenceless — as we are so often privy to indirect glances providing some form of humanization to the subject. “Lips” while providing this woman with eyes (behind glasses, indirectly gazing) she again, has no arms and no legs. The ominous and disembodied mouth above her does not seems not to be hers — the lips upturned in a foreboding smile, while pairs of hands reach towards (again) exposed breasts and her face. She leans away from these hands, an attempt to escape their grasps. You might not be able to make it out from the picture, but “Lips” makes use of text, bracketing her breasts with the words ‘BLAM’ — it’s all just so gross. Together, “Nude (for Sedfre)” and “Lips” demonstrates a pendulum of violence against women’s bodies: passive and desirable with no way to defend, swinging towards unrequited actions as the disembodied hands of unknown assailants reach towards her vulnerabilities. What’s worse but the gun etched onto her forehead as if to say, place here.

Colleen Mah’s piece locks eyes with the viewer, her lips painted perfectly to match those that bookend her; a detail which feels out of place for the tone of her expression. For me, this piece is not about a bad hair day, but a general disdain for what waits her as she grows up — or perhaps has already started to take place — as adults project a maturity upon her which she is years away from reaching.

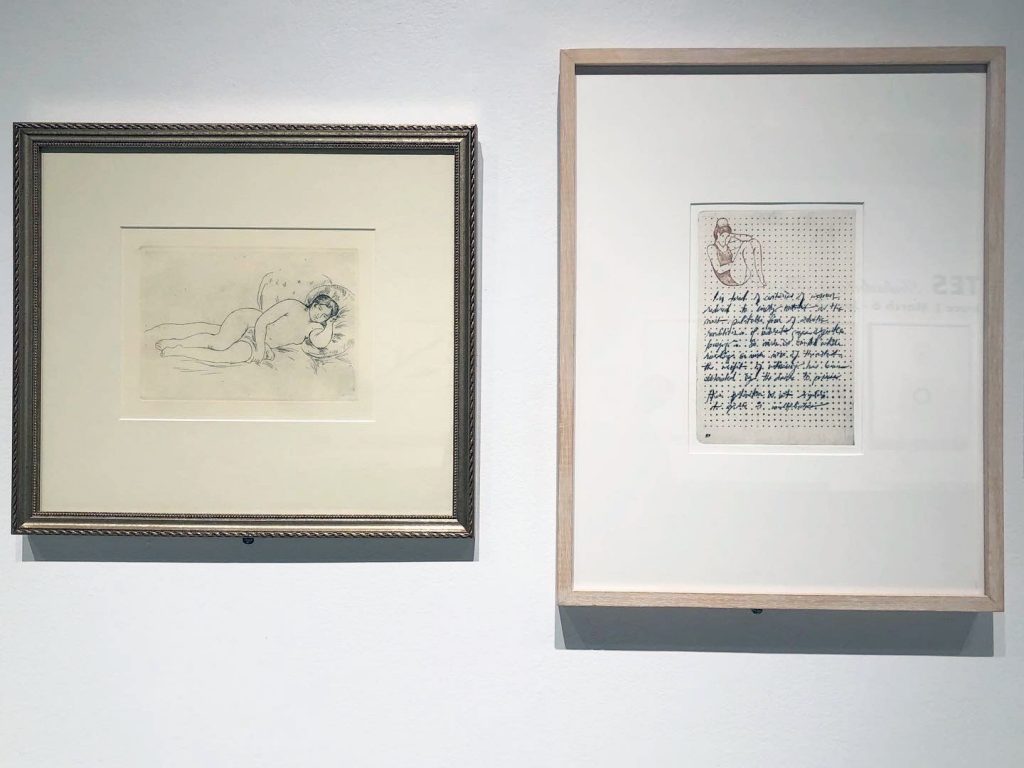

The text in my three plate drypoint print reads, “I’m tired of centuries of women reduced to empty contours as the most palatable form of artistic rendition. Of indirect gazes and gentle lounging. So much is omitted while revealing so much more of the artist. The weight of witnessing has been obliterated by the desire to possess. This exhaustion is not singular; it exists in multiplicities.” It’s strange, to have my little print next to a Renoir from 1906, but it confronts the tropes in ‘Femme nue couchee’ without being specifically about it — truly it applies to many of the depictions by other male artists here. My words were written in slow chunks through my notebook, coming to me while printing the other projects, and coalesced before I had chosen the short list for the collection pieces, finally arrived in their own print. The colour for the figure is the same from the bruise prints, not yet shown in this “tour” — a reference to the tenderness required for this work and the potential for hurt in allowing that softness through.

The last two prints on this wall for our #stayhome tour: “a doubling” [left] and “Sun and Moon” by Ernest Fried [right]. Content aside, the mark making in “Sun and Moon” is really lovely: stippling, over-hatching and a wide variety of etching times and engraved lines makes for a dynamic palette of marks. But content is dicey — sure, there is an implicit dichotomy of day/night and we get a nude dude(!), but the woman depicted is literally overshadowed by the aggression of his form. Her face shows clear distress, but her voluptuous nature dominates the viewer’s attention at a quick glance, her face dissolved into the shadows. Placing “Sun and Moon” with “a doubling” might just be about a lack of face, or a replacement of face with abstract emotion. It might be about the relative similarity in dimensions of print. It might even be about the gentle double lines present in both on the contours of my form and Fried’s. But when I look at these prints together, I see a woman in her body, on her own terms, and a woman no longer autonomously existing; her boundaries violated — even the shadow behind her falls further away as this interloper enters her space.

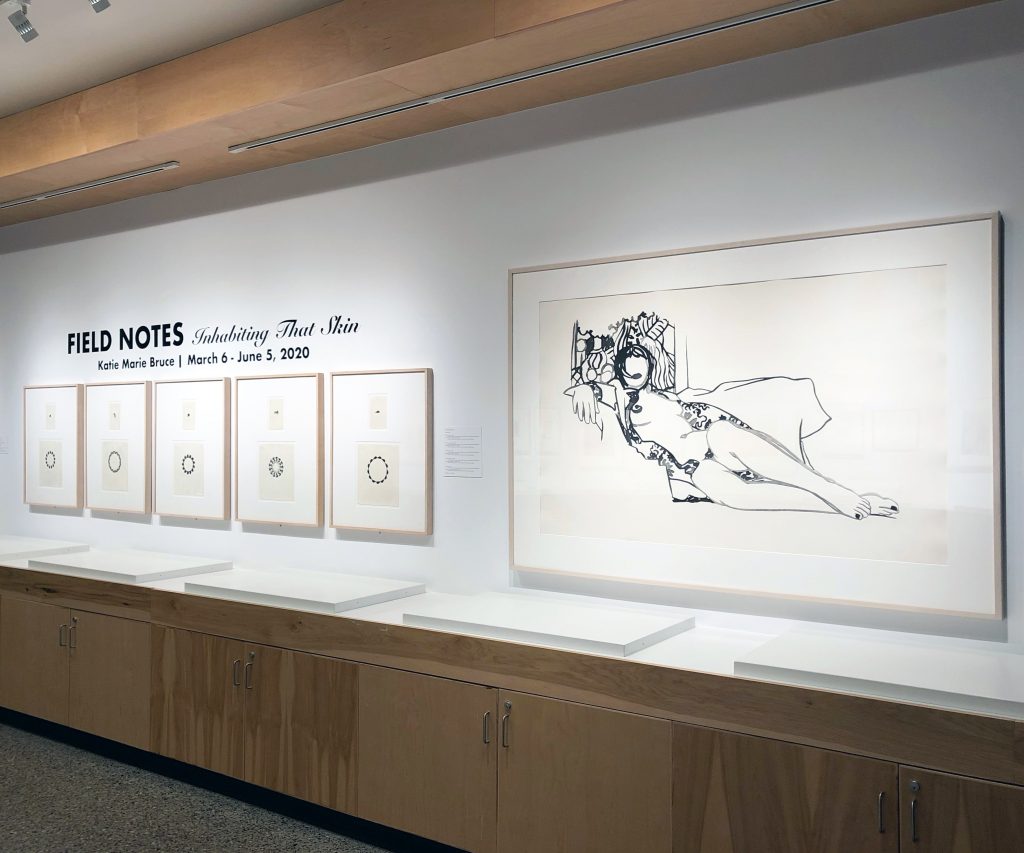

The contrast here is a simple one: my small exhausted figures next to the larger than life relaxed figure in Tom Wesselmann’s “Monica Nude with Matisse,” her confidence in this pose absent from any of my own self-portraits (a reality check, perhaps). His is a stunning print in person, technically very impressive. However, she has no eyes and her body is clearly scripted for the viewer, revealed by an open and ornate robe. These were the qualities that jumped out when viewing it through the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery online catalogue, and what inevitably landed this print on to my long list.

Seeing it in person though, I realized that her face was a similar size to the “clocks” I had arranged from the exhausted figures; the semi-floral arrangements created by repeated bodies mirrored pieces of the pattern in her robe. Certainly happy coincidences, and ones that made innate sense to explore

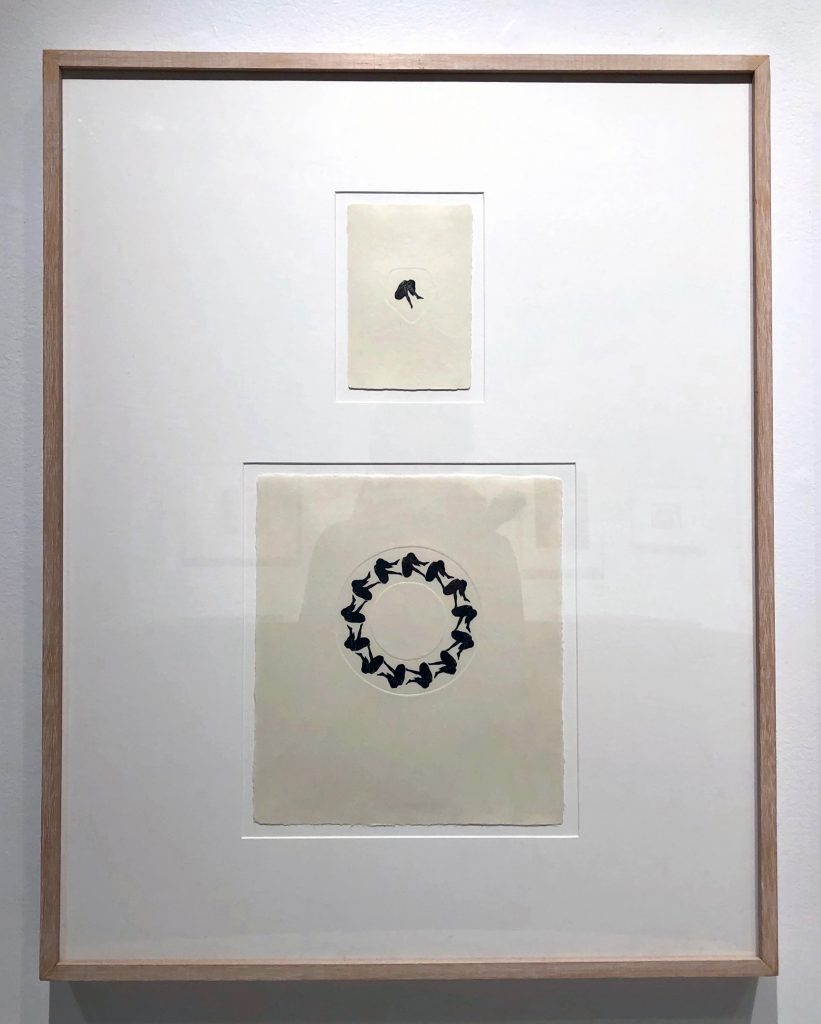

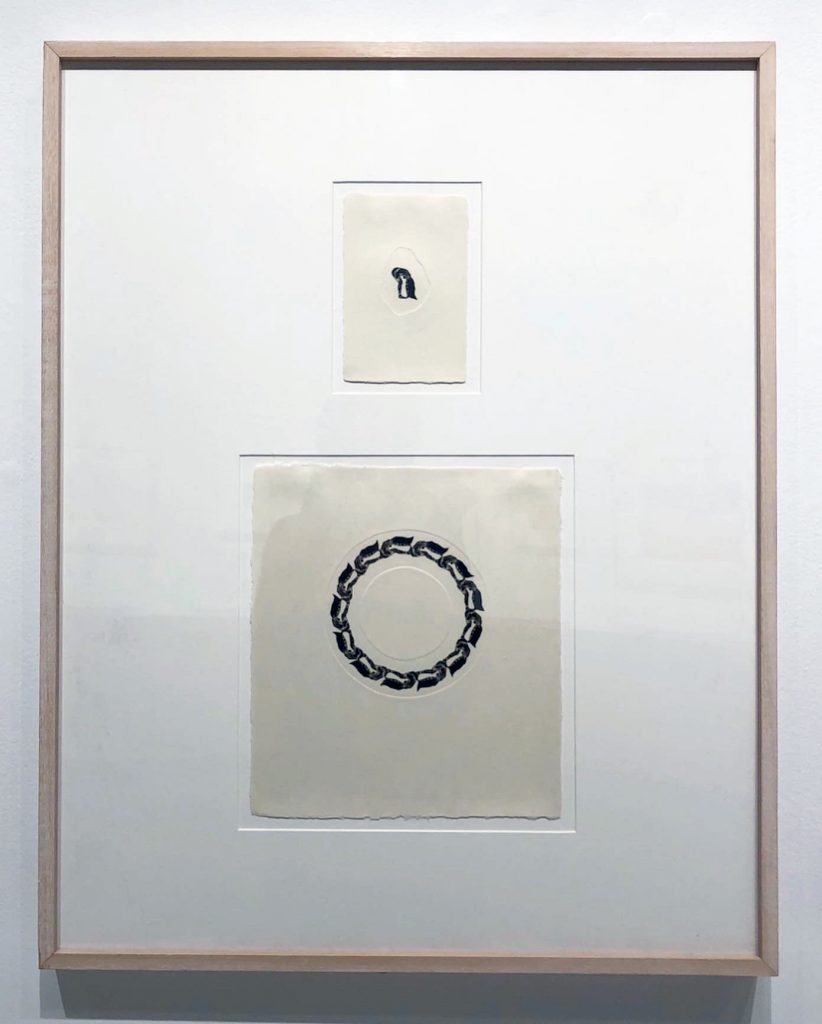

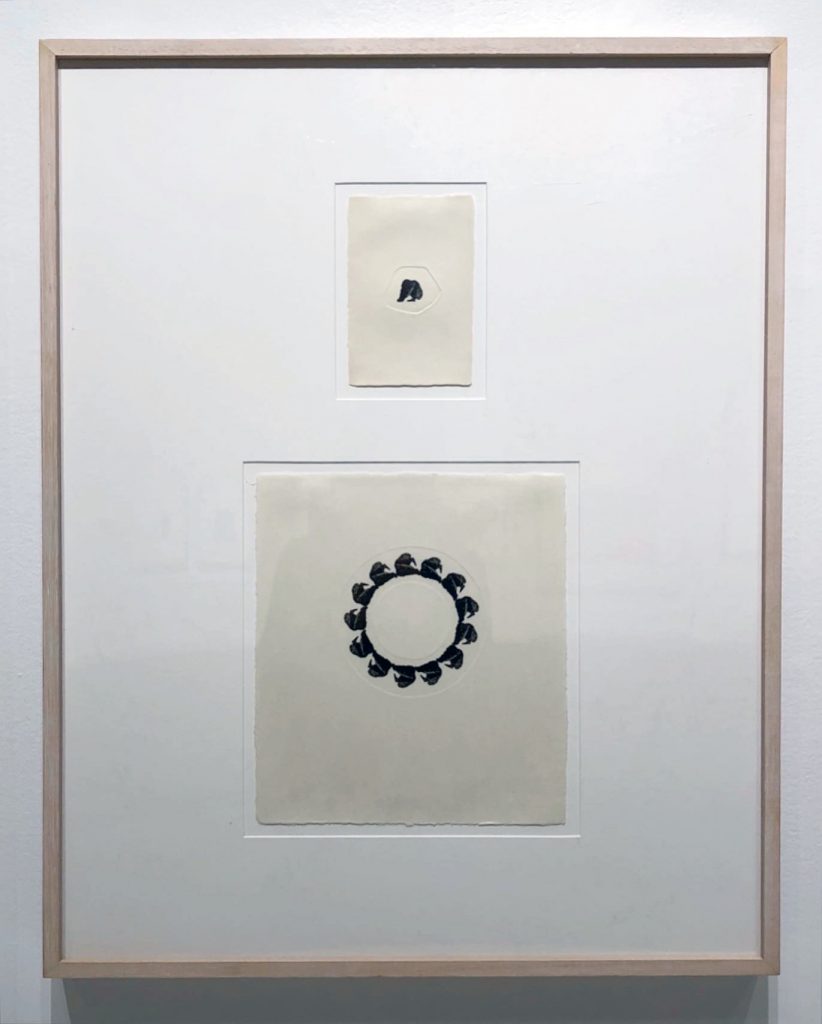

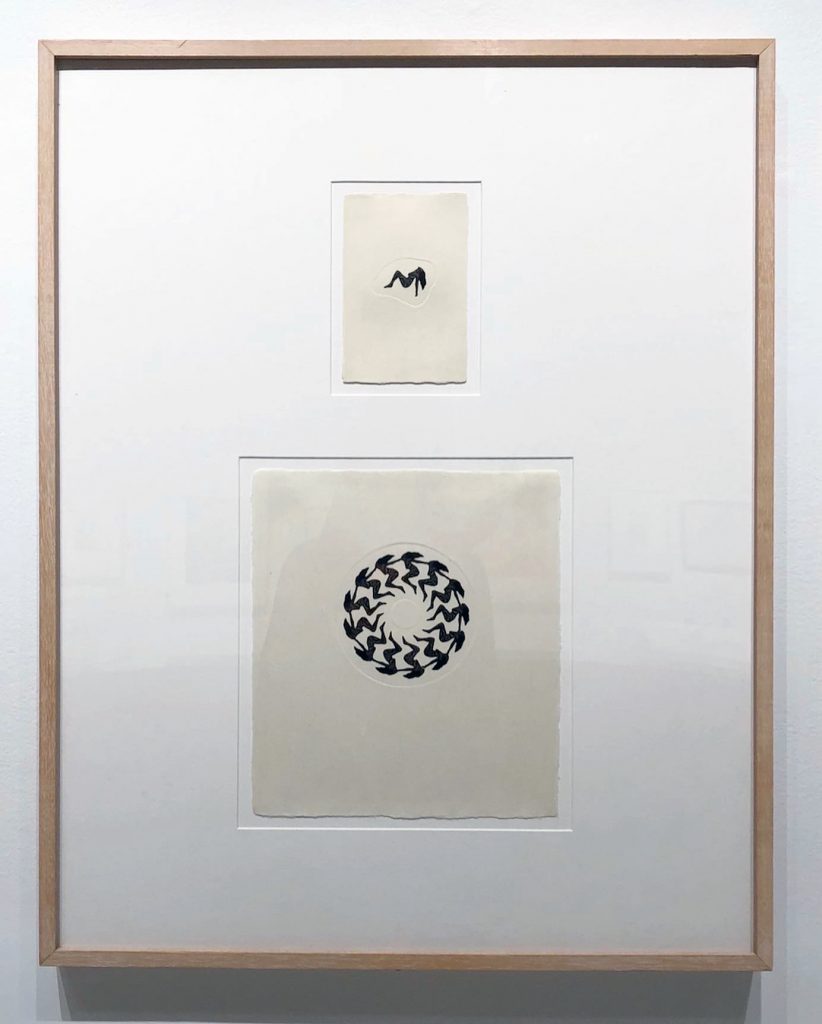

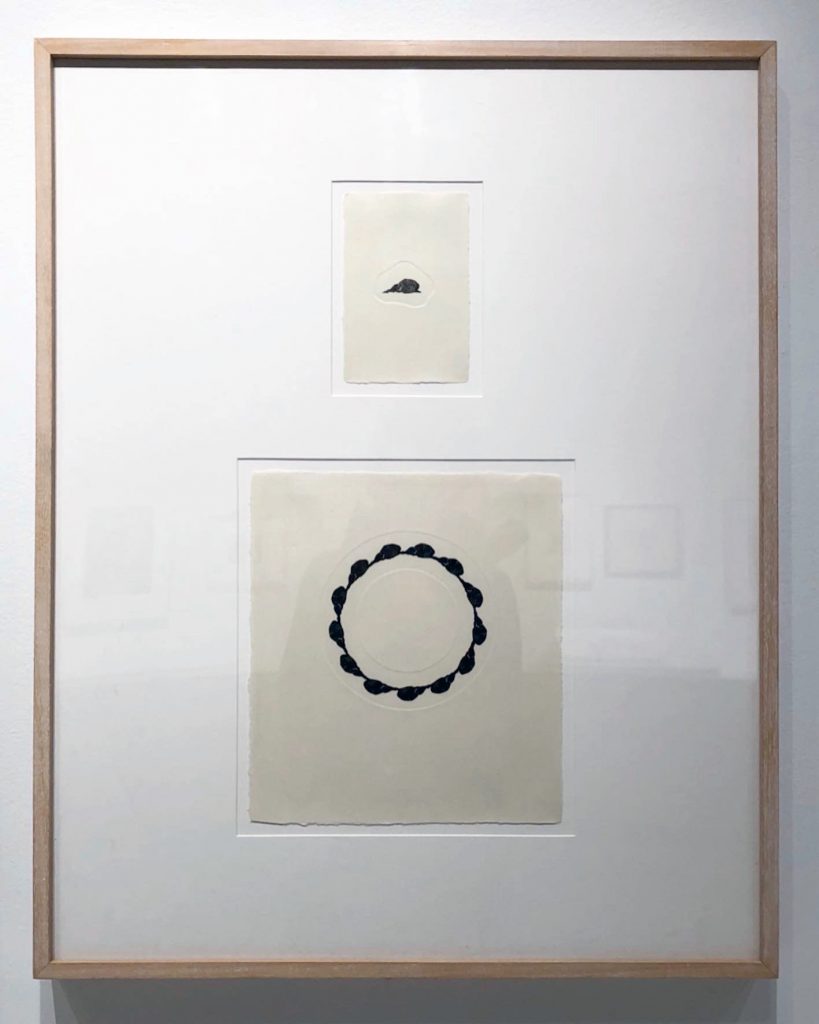

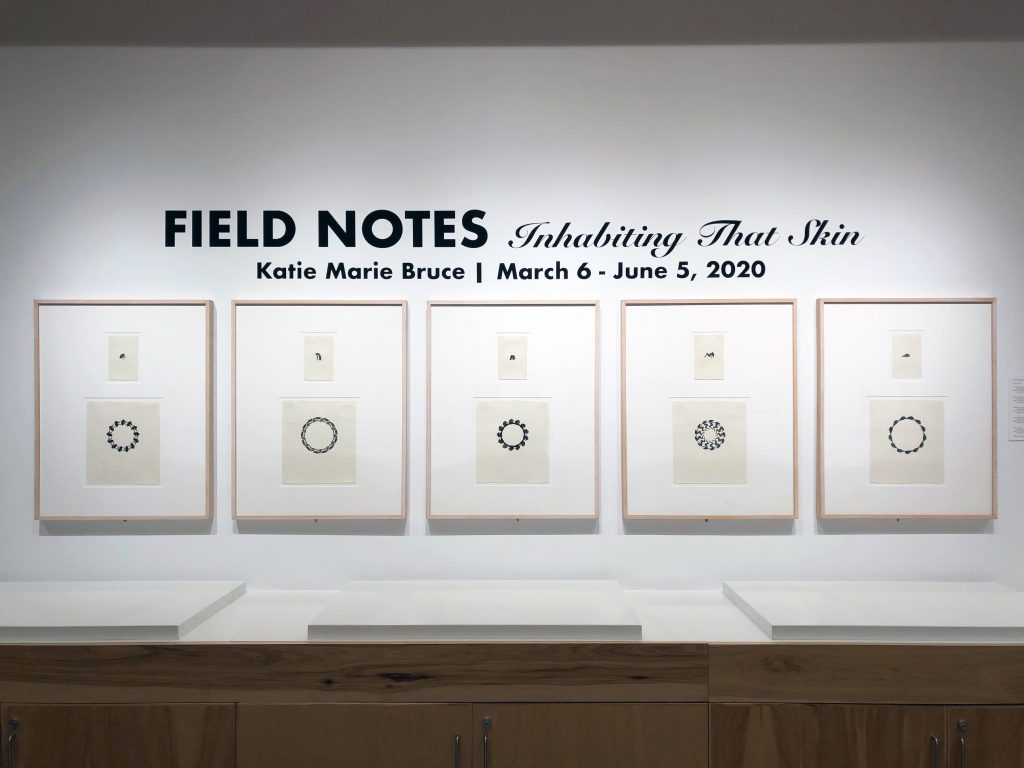

Since 2018, I’ve been printing small, exhausted figures — thinking about emotional residue and how it cloaks one’s body. They are Very Small, the printed surface measuring 1.25” or smaller, at their longest dimension; a nod to how we minimize this apparently-universal femme exhaustion, despite how large it looms. The poses are true to form: these are how I find myself when I need to acknowledge associated pains and exhaustion. While it helps to be in one’s body this way, the feelings never really release; from this realization the series “states of permanence” was born, each containing thirteen prints carefully cut out and placed in a circle. Thirteen was initially arbitrary — the first arrangement just needed thirteen to be a full circle with minimal overlap, in a size that felt relational to the paper. But in realizing they were both chain and clock at once, this never ending feeling needed more than an average clock worth of hours, so thirteen remained across the other four pieces. I wanted both representations of these feelings present in this exhibition — in perpetuity and in solitude — and luckily, I got to work with the very talented and patient David Smith, who seemed to not bat an eyelash at my request to float two prints in a single frame, times by five (what luck to work with such wonderful individuals through this).

The last two prints on this wall are “Jolly Corner” by Peter Milton (which, title alone is …the most eye roll) and “Nude by Night Window (Fisher’s Maid)” by Christopher Pratt. They’re both beautiful examples of media specific markmaking — “Jolly Corner” a stunning etching with the build up of short, repetitive marks creating stunning and undulating surfaces, while “Nude by Night Window” makes excellent use of those rich blacks that lithography is unparalleled by. And then they rapidly give me feminist heebeegeebees: why so voyeuristic (we’re inside, not looking through a window, so why not give her a face in this intimate setting), why is she first an anonymous nude and then only validated by her relation to an unseen other, why do these compositions (both internally and as installed) so brutally force us to consider why men get clothing and distinguished profiles, why are all the women nude/why are their bodies considered so ‘palatable’ that these questions (and similar ones) go unasked? These are the first half dozen observations that run through my mind and it doesn’t get less critical from there. These two prints create the other bookend to the large Wesselmann piece, cinching their male point of view of women around my lived experience.

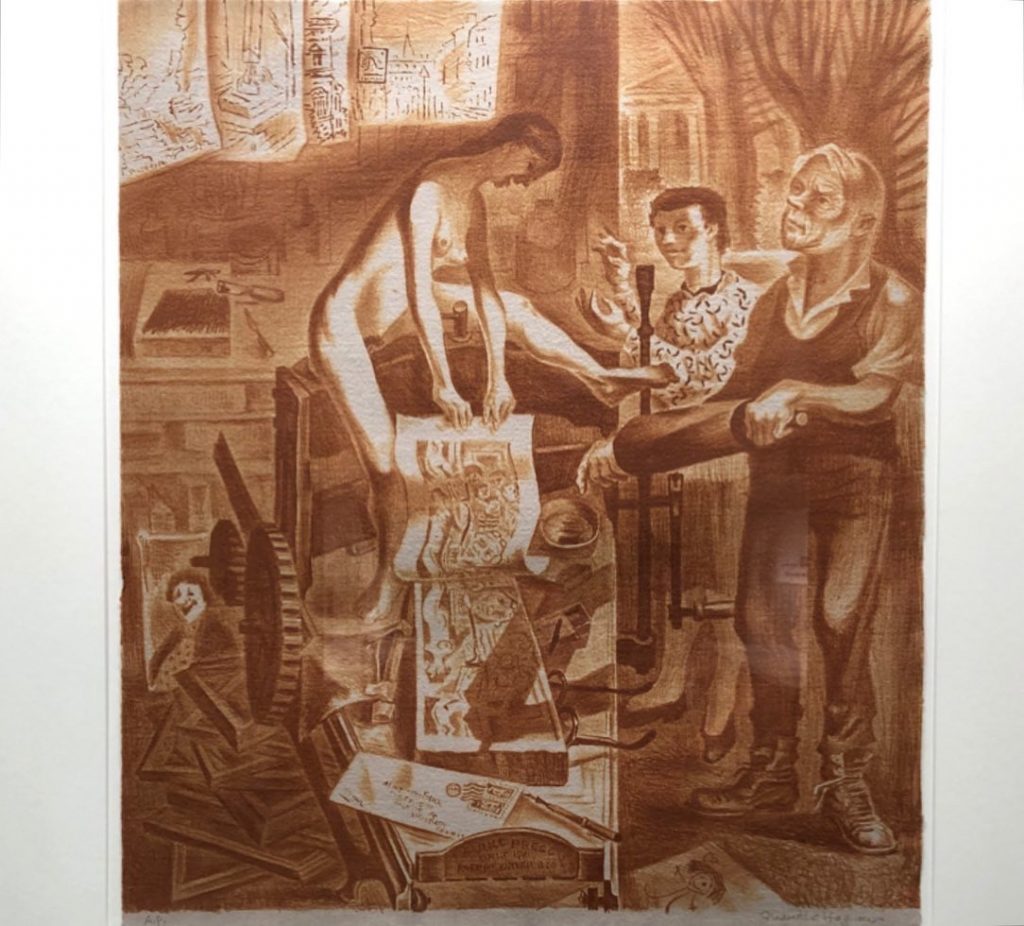

The end wall at the Helen Christou gallery has great appeal — it announces the tenor of an exhibition before the audience has necessarily viewed any of the passageway works. When considering this wall, I wanted to include some of the work that provoked the strongest emotions in me; the pieces that drove my attention away from exploring print techniques towards paying attention to how women were depicted by male artists. I chose not to show pieces from the portfolio of lithographs by Walter Bachinski which truly provoked A Lot of Feelings — instead using Fred Hagan (his mentor’s) work. Their pieces aren’t derivative, but I might argue there is some inherited treatments and perspectives shared between them of women’s bodies and their experiences. While Bachinski’s “After Birth” pieces really had me starting to question who has the rights to certain narratives, it was the repetitious images of Hagan’s pieces that had me seeing red. In multiple colour ways (not as a variable edition, but as their own works), nude women lay in or crawl through tall grass, simplified down to ass and thighs and deprived of any kind of real personhood. There was something obsessive in the need to produce these variable images: the cleaning of the stones between printing and preparing new rainbow rolls alone …the labour alone is unreal, and worse if you consider that it may have been an assistant’s labour. And the images, in my opinion, are undeserving of it. All of these feelings were before coming to this glorious image in the middle here, of a Very Naked woman standing on a litho press pulling a print, while her companions stood inactive and clothed. The absurdity alone is astonishing.

I’ve paired these five prints with my thigh bruise prints in two healing states. I wanted a body present to have feeling, as mine does. To show a progression, instead of stagnation. And to be relevant to the women (imagined or not) who wouldn’t have escaped these scenarios unscathed. The bruise is a metaphor for healing, encapsulated in real-time, relevant to the past present and future. A field note like observation of being in a body.

I wanted to provide a few angles of the bronze sculptures. The illusion of suspension correlates nicely to the way knots, blocks, and thoughts live within my body; their shadows fall softly and diffused, reminding me of the way those spots echo with the tension once held, even once released. They act as observations of things that can’t be seen, only felt.

Which leads us back here, to ‘autopsíā’ — an imagine I started thinking about around this time last year. A quick scrawl in my notebook “a women made of knots” became a note in my phone late last year: “diptych 6×12/mirrored pose/ asymmetrical knots/equal background tone/blue black mezzotint hair/two editions (singles; together)” — this is how I process a print idea; it’s rare that I work through an image with drawings before I really commit to making it. of course there were mid-night notes that evolved the print through various stages, including a note about a possible title for a potential print. ‘autopsíā’ is the root word for autopsy, but means “seeing with one’s own eyes.” I came across it in “Library of Small Catastrophes” by Alison Rollins, a beautiful book of poems about the body and holding grief and loss. Knots carry a lot of potential meaning and grief certainly resides there, but not by itself. Compounded by conversations left at the back of my throat, general anxiety, unrequited feelings, worry turned paralysis, unknowns, unresolved resentment, concerns that line my inner lip — grief, is never alone in me. And even as I work through these knots, listening to what they have to say and untangling their real meaning, they leave imprints when they’re untied like bedsheets after a heavy sleep. Whether filled with sensation or empty and calm, these knots live here, always. So the last piece on our #stayhome tour is an honest self portrait, split by the days I simply feel the presence of this anxiety and the days I can’t see past it.

And this brings us full circle, so thanks for indulging me folks. “Field Notes: inhabiting that skin” has been extended through the summer, but stay home folks [until it’s safe]. Much love to the whole University of Lethbridge Art Gallery staff who have been absolutely supportive and enjoyable to work with through this project.