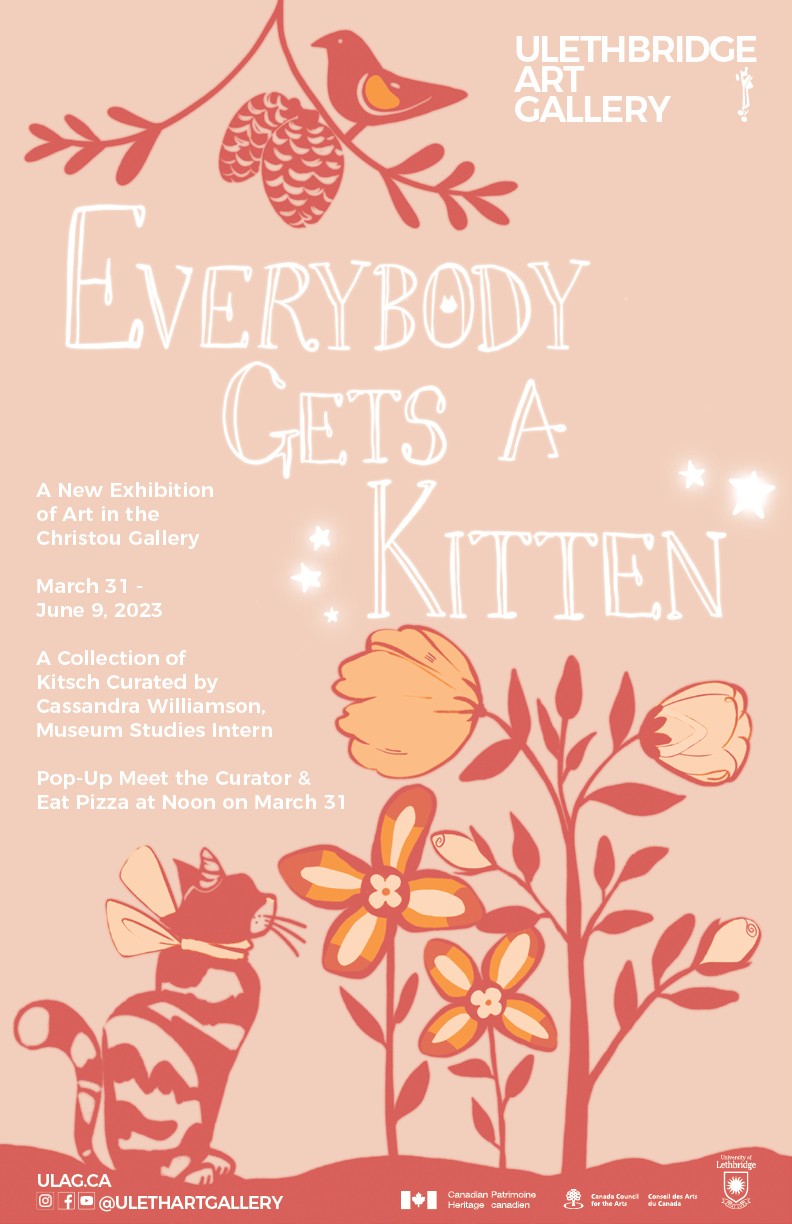

Helen Christou Gallery

Everybody Gets A Kitten

March 31 – June 8, 2023

Curator: Cassandra Williamson, Museum Studies Intern

A collection of Kitsch pulled from various sources and the ULethbridge Art Collection.

What is kitsch? What does it mean to say something is “kitschy”?

These were the questions at the forefront of my mind as I developed this exhibition. Taking into consideration both art theory and localized understandings of the term, I wanted to explore the meaning behind this word that not everyone knows, but seems to strike fear and disdain in the hearts of artists and art critics alike.

The term “kitsch” was first used in 19th century Germany to describe commercial folk art sold at markets and fairs like Oktoberfest, as well as the emergence of mass-produced consumer goods that came with industrialization. Although the exact definition varies depending upon with whom you’re speaking, kitschy art and aesthetics are considered bad taste; they are tacky and cheap, overly sentimental, cheesy, or simply reproduce a well-worn set of visual conventions. Think sweet illustrations of fluffy kittens or star-crossed lovers, tiny versions of the Eiffel Tower, floral wallpapers and the endless reproductions of Van Gogh’s Starry Night onto every surface and product you could possibly imagine.

“Kitsch” is generally considered to be a negative term, indicating that the described object or artwork is tasteless or unrefined, indeed, it is most often used to denote visual expression which does not meet the conceptual depth or innovative criteria of the avant-garde or so-called high art. Some discussions of the term assert that kitsch is “bad” art, or, most interestingly, not “art” at all. The boundaries between kitsch and fine art must be understood as highly contingent and fluid, a concept most clearly illustrated by the Pop Art movement of the mid to late 1950s, wherein mass-media imagery and consumer tastes became the preferred subject of artists who wanted to comment on popular society and question notions of artistic genius and fine art. Works by Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and their contemporaries may have been criticized in the beginning, but their now iconic images of soup cans and tearful women are firmly part of the art historical canon. Except, perhaps, when they appear on a tote bag.

The dynamic and highly subjective way of classifying art or visual culture as “kitsch” is explored in this exhibition by the inclusion of objects and artworks from outside the University’s Fine Art Collection. Knick-knacks and prints, both handmade and commercially reproduced, are placed alongside collection works to elevate their status from everyday kitsch to valuable art objects. Both collection and non-collection works are displayed and labelled to gallery standard and the immediate distinction between the two is intentionally left unclear. This decision acts to draw attention to the role of museums and art galleries as arbiters of good taste and authorities on visual culture. It also encourages visitors to examine the similarities between accessioned fine art and informal art objects, drawing parallels between the two and considering why one is seen as more artistically or culturally valuable than the other.

Despite kitsch’s low status in the art world, it remains overwhelmingly popular and enjoyed by many. Folks are drawn to imagery that makes them smile, makes them laugh or reminds them of their childhood – kitsch is the familiar, it is the nostalgic, the warm and endearing. Kitsch thus plays a particular role in people’s lives, serving as an affirmation of shared sentiments and values, and providing an accessible and enjoyable aesthetic experience that is different from (but not necessarily less valuable than) what is provided by the highly conceptual avant-garde. When we feel secure in ourselves and our lives, we seek out challenging experiences that encourage us to learn and view the world differently – we might go to an art gallery to see an innovative exhibition of contemporary art that deals with difficult truths and explores the complexities of human existence. But when we are feeling worried, stressed or unsure of ourselves or the world around us, it is kitsch that we tend to find more appealing, it is what we turn to in times of chaos and anxiety. Kitsch becomes an important part of our shared identity, reminding us of happier times or providing an effortless and positive experience that makes the world seem a little brighter.

Cass Williamson

Curator