Online Exhibition

Stories for British Museums

November 1, 2020

Work by uLethbridge Indigenous Art Studio students in response to Blackfoot historical objects held in the British Museum, the Museum of Archeology and Anthropology at Cambridge University, and the Horniman Museum in London, England.

The presentation of the artworks in this online project, like so many things from 2020, is not what it was supposed to be. Students enrolled in the spring semester of the “Indigenous Art Studio” class with Dr. Jackson 2Bears had made artwork for an exhibition in the ULethbridge Art Gallery’s Hess Gallery. Scheduled to open March 19, 2020, students were dropping off works and busily finishing up their projects when the university had to close because of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the Art Gallery was left holding some finished works, some works that needed to be installed by the student artists or needed further components, and some artworks had not yet been delivered. As we all adjusted to closures of public spaces and working from home, the issue of how to finish this exhibition hung over us.

The uLethbridge Art Gallery is still closed as I write this in November, 2020. The space has stood empty since that week in mid-March when we were about to start installing this exhibition. Once it became clear that the closure of the exhibition spaces would continue for the rest of 2020, I recognized that we had to cancel the exhibition, but we didn’t want to abandon it entirely given that it was almost completed. We began to ponder how to present an exhibition that never happened and how to represent work that was not finished.

The students had done a fabulous job, working hard and engaging with processes, concepts, and imagery of objects involved with Mootookakio’ssin – a major research project to create detailed digital images of historic Blackfoot objects housed in three museums in Britain. (For further information, see the end of this text). We had promised the students an exhibition and they had put in extra effort to make work that could stand up in a public display. As well, they were the first group of students to tackle the daunting task of working with the Mootookakio’ssin project. Their exhibition was to provide an initial stepping-stone as we brought students from or living in Blackfoot traditional territory together with students working with our partners in Britain: Louisa Minkin at Central St. Martins, University of the Arts, London and Ian Dawson at the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton.

To begin Mootookakio’ssin, the Canadian component of the team, which was made up of Elders from all 4 tribes in the Blackfoot Confederacy, uLethbridge researchers, and artists, travelled to Britain in July 2019 to meet up with the British team members. Together we visited the British Museum, the Museum of Archeology and Anthropology at Cambridge University, and the Horniman Museum, London to view Blackfoot objects that had come from Blackfoot territory (Southern Alberta, Canada and Montana, USA) and now are held in these collections in the UK. The Elders selected the objects we looked at, told stories prompted by the objects, and the team made digital images of the objects. It was my first time visiting museum collections with Elders to look at Indigenous material. Words fail to describe how deeply moving and emotional these visits were. For the Blackfoot, there is no equivalent to the term “object” because all things are living beings – the ‘objects’ have a life force and the Elders were waking these objects after a century or more of separation from their people. It’s hard for non-Indigenous people to conceptualize this crucial idea of the connection between the objects and the people, of the life force that they each generate in the other. With those visits, it became clear to me. I felt it and could see how lifeless and incomplete the objects were without the people to wear them, use them, and have them play their role in telling stories and sharing knowledge.

It seems obvious now, but I didn’t see the connection with the uLethbridge Indigenous Art Studio student’s work until I went to look at them in person on campus in October, 2020. As the university was closing and students were being sent home in March, we had put the students’ artworks in a storage room in the Art Department. We wanted to keep the work safe during lockdown. Other than two staff who took turns going to campus to check on the University’s art collection, the rest of the gallery staff worked from home for several months. When restrictions began to open up, I went with David Smith, Assistant Curator and Preparator, to look at and remind ourselves what student work we had as we began to think about an online version of the exhibition. Standing in that small storage room, I felt so sad looking at objects that lacked the vibrancy of the artists, the energy surrounding the exhibition; works that were incomplete, that didn’t have their context. And then it struck me, this is like visiting the historical objects in the museum storage in England.

I keep being surprised by the ability of the historical objects to convey information. As a curator, I shouldn’t be, but perhaps it is a case of not being able to see the forest for the trees. When we first started Mootookakio’ssin, I was shocked by how many non-Indigenous people asked why the Blackfoot objects are in museums in Britain. This question came from people of all ages and walks of life. The Elders gently laughed when I told them about my surprise. They explained that by answering the question, I was achieving our goal to build connections between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and perspectives. The objects themselves provide the means to explain the on-going legacies of colonialism. As a curator, I know the importance of art, yet have overlooked the power these objects have to dismantle colonial narratives and to rebuild relationships between people. Talking about the objects opens doors and creates paths to understanding. What better way to interrogate colonialism than to address one of its core products: the museum? It is like taking an engine apart to understand how it works so that we can make something better. There is much that we need to build new as our team puts Indigenous material on the Web in a way that reflects Blackfoot values and as we organize exhibitions and audience relationships with them.

Here in Lethbridge, standing in the small storage space looking at the forlorn student art works that had been left behind when the quarantine began, I learned one the many important lessons I am gaining from working on Mootookaikio’ssin. I realized that non-Indigenous viewpoints also include a vital connection between people and art works, even if we don’t conceive of the objects as living beings. Stories for British Museums, the inaugural ULethbridge student exhibition connected to the project, has provided a crucial first step in building connections between the historical Blackfoot objects and current artists and audiences. The version presented here on the uLethbridge Art Gallery’s website is not the same as the exhibition that never came to be, yet it is a valuable link in the research process and demonstrates the strength of the artwork produced by the student artists.

Josephine Mills, Director/Curator

About Mootookakio’ssin:

Mootookakio’ssin aims to connect people living on traditional Blackfoot territory (Southern Alberta, Canada) with historical Blackfoot objects housed in museum collections in Britain and uses digital imagery to record objects in great detail. The project’s title, Mootookakio’ssin, was given by Elder Leroy Little Bear and translates to “distant awareness.” Elders from the four Blackfoot tribes, Kainai, Piikani, Siksika, and Amskapipiikani, are directing the project and selecting the museum objects. The digital imagery belongs to the Blackfoot people and will be accessed on-line through the Blackfoot Digital Library at the U of L (include BDL web link). The Mootookakio’ssin project is only making images of non-sacred objects available to the public. The project is funded by a grant from the New Frontiers in Research Fund, administered by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Christine Clark, from the uLethbridge Department of New Media is the Principal Investigator for the grant, and is leading the development of a micro website that presents the digital images and their associated knowledge. The website is currently in process, but you can visit it for further information: https://mootookakiossin.ca/.

Stories for British Museums Participating Artists:

Ines Catalini

Xiaosi Chen

Kale Fox-Zacharias

Kim Frondall

Bailey Lamarche

Raven Limpy

John Little Bear

Jake McIntyre-Dilley

Loraine Menicoche-Moses

Owen Schieber-Healy

Shelby Soop

Danielle Tailfeathers

Serene Weasel Traveller

Yundi Wang

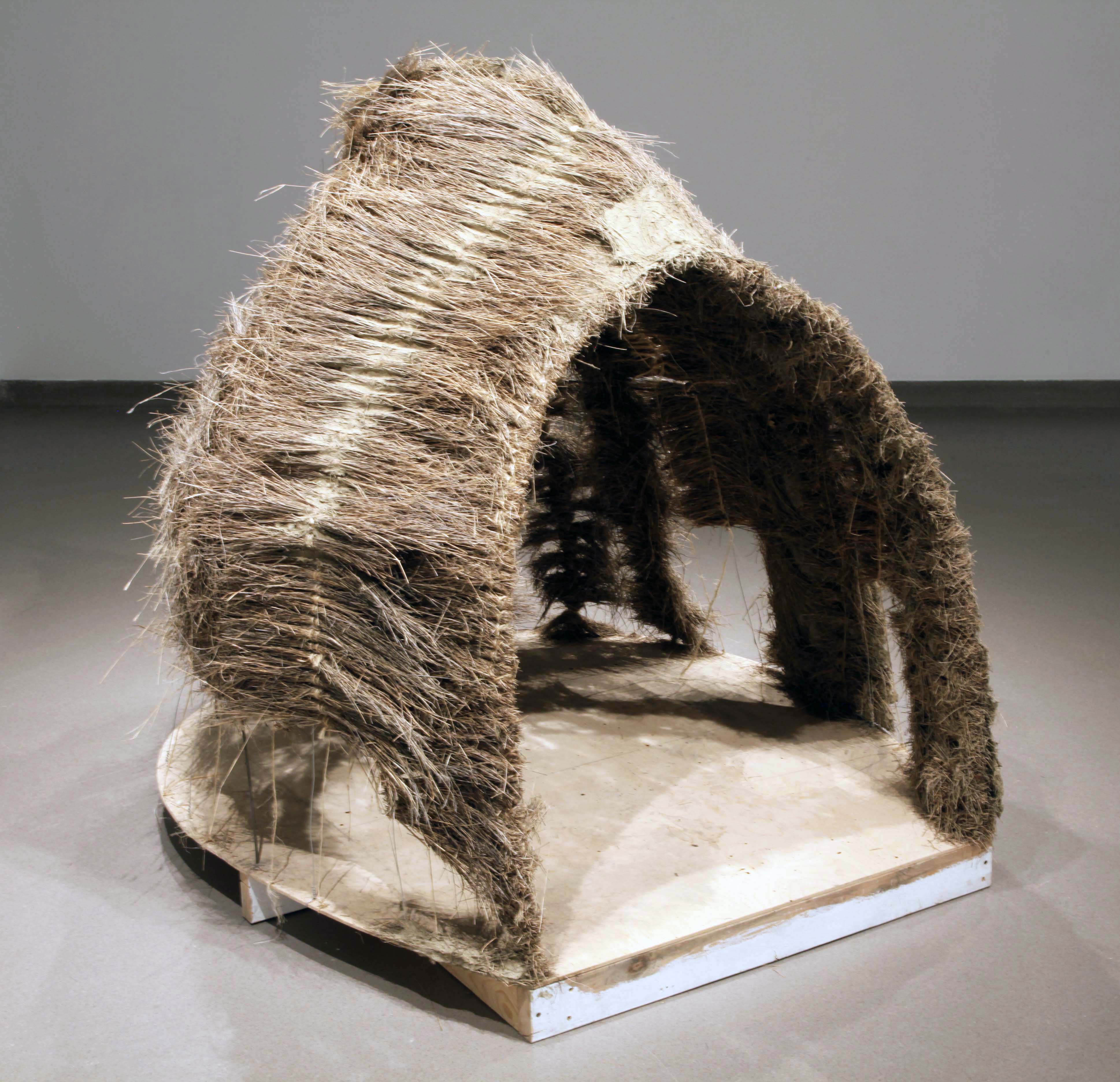

INES CATALINI, Come Over, Mixed media installation.

XIAOSI CHEN, Welcome to Blackfoot Territory, Printed matter.

KALE FOX-ZACHARIAS, Iikakimaat, Iniiboka, Mirror, adhesive, glass cutter and photogrammetry.

Note from curator Josephine Mills:

Kale created several small sculptures of buffalo that had differing reflective surfaces. He created the sculptures to be imaged with photogrammetry and so that the reflective surfaces would be difficult to capture. In the exhibition, Kale would have included the sculptures along with the photogrammetry video. We do not have regular photographs of the sculptures.

KIM FRONDALL, Nanny’s Chair,Ceramic and quilted fabric.

BAILEY LAMARCHE, Reclaiming My Root, Handmade paper with dyed fish scales and paint.

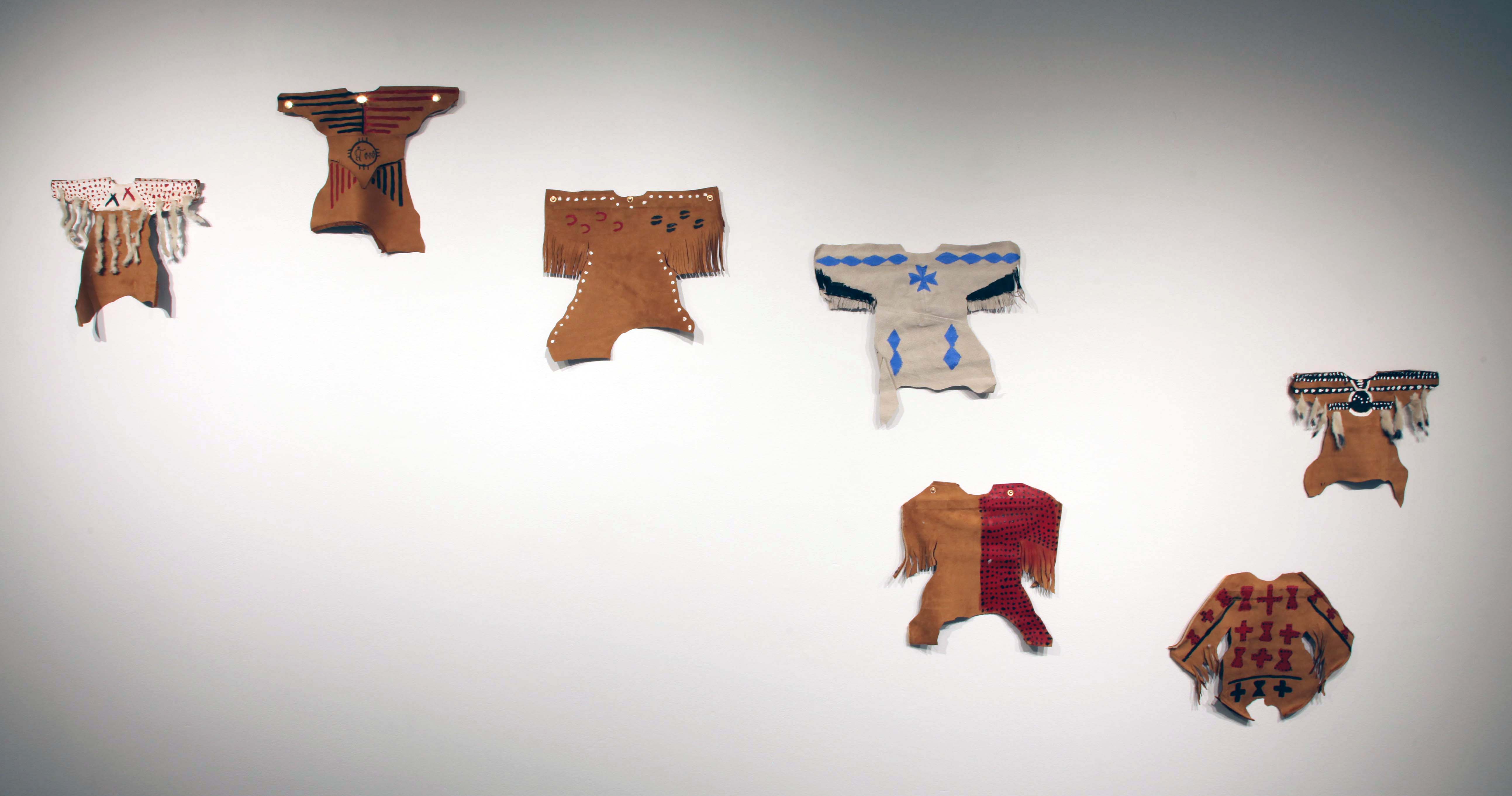

JOHN LITTLE BEAR, Ihkitsikammiksi ( 7 Brothers/ Big Dipper), Acrylic paint on leather and suede.

JAKE MCINTYRE-DILLEY

Note from curator Josephine Mills:

Jake took on an ambitious project to incorporate her training as a tattoo artist and had planned to ink a tattoo on a collaborator as a performance during the opening of the exhibition.

OWEN SCHEIBNER-HEALY, Perspectives, Mixed media on canvas.

Note from curator Josephine Mills:

As we post this, we have been unable to reach the artist. We wanted to include his powerful work, yet we know that it is missing half of the effect for the viewer. Owen’s painting of a residential school incorporates colour to create two potential images: for the exhibition, it was to be installed with a light on a timer shining through a red gel; when the light came on, different components of the painting would become visible.

SHELBY SOOP, Oppression, Mixed media.

SERENE WEASEL TRAVELLER, Itsikin, Vans “Off the Wall” and glass beads.