Out of the Ordinary: Annual Curated Student Exhibition 2011

Main Gallery

Reception: March 11, 7 – 9 pm

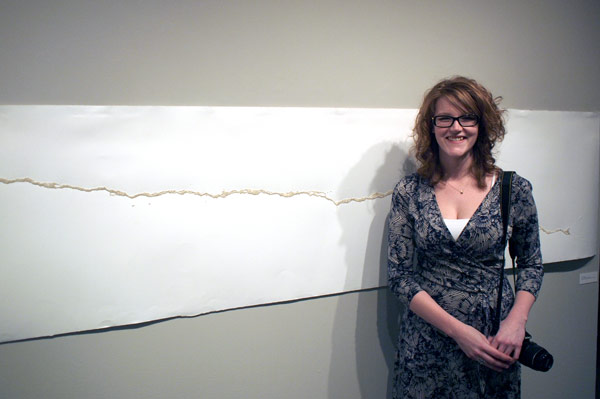

Guest Curator: Emily Falvey

Selected artwork from Senior and Advanced Studio Students.

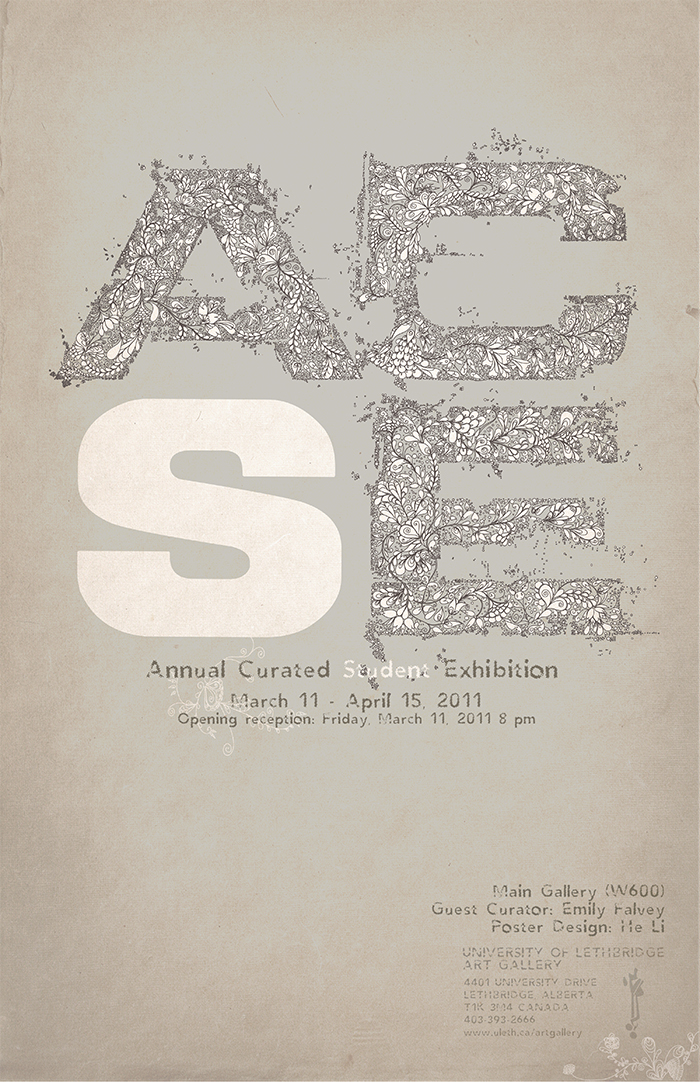

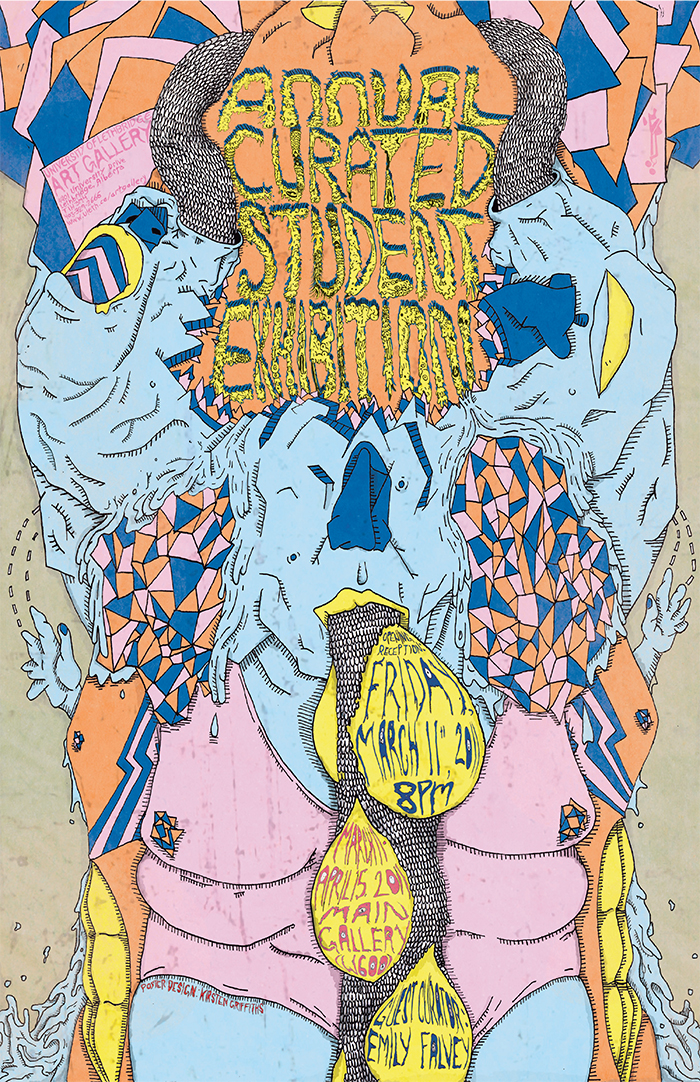

Exhibition Posters Designed by He Li & Kirsten Griffiths

The University of Lethbridge Art Gallery provides an exceptional opportunity for the professional development of Art Studio majors as they near completion of their degree. The Annual Curated Student Exhibition has recently been revised to give students realistic experience with the process of applying for exhibitions and receiving feedback from an established curator. The exhibition is only open to senior art majors in order to focus attention on those with the goal of becoming professional artists. In applying for this exhibition, the students follow the same process and standards for documenting, describing and proposing their art work as they will when applying to public art galleries and artist run-centres or for grants. Staff from the Art Gallery provide advice on preparing the proposals and share insights into what curators look for when deciding to book a studio visit and choose art work for an exhibition.

An established curator from outside of Lethbridge is invited to create the exhibition. The curator views the proposals and selects a short-list of students for follow-up meetings during a visit to Lethbridge. From these studio visits, the curator makes the final selection and works with the Art Gallery staff to lay-out and install the exhibition.

The Annual Curated Student Exhibition provides a showcase of excellent work by Art Studio majors in that year and gives the students a valuable achievement to list on their résumés. As well, the students who are not selected receive feedback on their proposals and can learn how to improve as they prepare to begin their careers.

Visit the Faculty of Fine Arts.

Artists (click image to enlarge)

Donna Bilyk

Donna BilykChip Painting, acrylic on chipboard, 2010

Chip Painting – Details, acrylic on board, 2010

Allison Crop Eared Wolf

Allison Crop Eared WolfIndian Act; Revised, handmade paper from the Indian act, hair, 2011

Indian Act: An Indian Perspective, Digital photograph, 2010

Bonnie Patton

Bonnie PattonpreFIXation, cedar wood, plastic, paper stickers, ink, typewriter ribbon, 2010

Remain Calm…, vinyl lettering, 2010

Arianna Richardson

Arianna RichardsonThe Hobbyist Collection, mixed media video, 2011

Showcase, cabinet, paper, 2011

Tinsel Tick, wire mattress, tinsel, pillows, 2010

Corinne Thiessen Hepher

Corinne Thiessen Hepher…eaten @ 1:55, video, 2011

not uniform suit, nylon pantyhose, polyester fibre, thread, 2011

Curatorial Statement

Visual art that explores the aesthetic and political potential of the everyday has a long and rich history. Although art historians usually associate this kind of work with modern and avant-garde artistic practice, it can in fact be traced to 16th- and 17th-century Renaissance still lifes, which used symbols of ephemerality—such as cut flowers, rotting fruit, small insects, and skulls—to both celebrate and caution against over-consumption. At the time, these detailed trompe-l’œil paintings were considered the lowest fine-art genre, and so artists were at greater liberty to experiment with them. In many ways, painters such as Cornelius Gijsbrechts (Antwerp, ca.1630-1675) and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (France, 1699-1779) laid the groundwork for pivotal 20th-century artists like Meret Oppenhiem, Marcel Duchamp, and Any Warhol, whose work turned mundane, found objects and images into vectors of outrage, wonder, and dread.

Out of the Ordinary revisits the practice of extracting unusual and unexpected forms and meanings from everyday materials and subjects. By creating work that incorporates or builds upon found objects, patterns, and text, the artists in this exhibition explore a wide range of issues, including states of contradiction, processes of legitimation, and acts of both violence and healing. Corinne Thiessen Hepher’s work, for example, uses costumes and body extensions to explore themes of metamorphosis and hybridity. Often constructed from found materials such as pantyhose, her work plays on the distinction between intimacy and extroversion, the beautiful and the grotesque. Less dramatic, although no less paradoxical, Katie Bruce’s prints focus on discrete cracks and other patterns that develop naturally in the built environment. Approaching these formations like readymade engravings, she uses them to emboss paper, then works back into the resulting image with embroidery. Also working with textiles, Jena Ursel explores the relationship between repetitive, ritualistic processes and therapy. Inspired by a personal struggle with depression, her work represents both a form of self-examination and a means of escape. In a similar vein, Kalen Hussey’s photographs consider the tension between strength and vulnerability by zeroing in on accidental and self-inflicted scars.

Among the more playful works in the show, Bonnie Patton’s preFIXation (2010) treats prefixes and suffixes as alchemical devices capable of transforming any word. A set of language games made from altered Rubik’s Cubes, handmade Scrabble pieces, and dice, the surreal randomness of this work is echoed by a text fragment enlarged to fill an entire wall. Combing craft techniques with found vintage and kitsch objects, Arianna Richardson’s multimedia practice critiques methods of assigning value based on a distinction between fine-art collectors and hobbyists. Brenna Crabtree’s ongoing series of bread tags explores the hidden formal possibilities of extremely banal subject matter, while Chad Patterson’s tactile sculpture, Salt Lick (2010), offers a playful take on the Duchampian readymade. Also referencing modernist frameworks, Donna Bilyk’s Chip Painting (2010) undermines abstraction as a form of individual expression by using programmatic methods and a limited palate of commercial paint.

Perhaps the most political work in the show, Indian Act; Revised (2011), by Allison Crop Eared Wolf (Blackfoot, Blood nation), deconstructs the offensive Act of Parliament used by the federal government to define who is an “Indian.” Motivated by a desire to both highlight and obliterate this disturbing document, she painstakingly shredded a copy of the Act by hand, turning the remains into sheets of hand-made paper. Embedded in each sheet is a lock of the artist’s hair, a reference to the Blackfoot custom of burying hair after it has been cut.

– Emily Falvey

Guest Curator

About the Artists

Donna Bilyk

The paint chip is a commonplace item you find when entering a paint store and begin searching for the perfect color for your painting project. As they are samples of the various colors of paint available and free for the taking, you invariably leave the store with a wide selection to match up the colors at home.

For myself, I experienced the paint chip from the standpoint of the consumer as well as the retail clerk responsible for mixing and testing the paint.

Through my personal experience with these paint chips I wanted to bring them out of the ordinary into our world on a life sized scale. For me they have always represented a piece of art. During my visit to the Louvre I was impressed not only by the art within the museum but also by the natural beauty of the gardens. When choosing my colors for the paint chips, it reminded me of the flowers in the garden. Within each grouping the commonality is green which represents the foliage of a flower.

I found as I travelled along this journey with the paint chips my work evolved into many directions. Recently, the works of Garry Neill Kennedy chip board paintings which were on display at the University of Lethbridge were an inspiration for me to create my own chip board painting. The complete palette of colors within my paint chips transformed themselves onto chip board.

As I continued to work on this project I found myself inspired to explore different avenues such as creating mosaic works, a series of chip board pieces and a macro detailed selection from my original chip board painting.

I have enjoyed this project and for me it has become a labor of love and a place to reflect, meditate and lose myself.

Katie Bruce

For myself, I find that the smaller, simpler, or more banal an object, the more I am intrigued by it’s existence. When the object comes about by accident, or without the direct action of a maker, I feel a further inclination to explore it. My studio practice is routed around the found texture; my current fascination lies within the cement fractures and fissures of the University of Lethbridge; the architectural history of the space. The ground has always been comfortable for me visually, both in the repetition and the anomalies.

This body of work, coming out of my senior studio practice, is centered around the process of hand embossing the ground, and then building upon the forms. Whether that process is a sort of curation, gathering, filling or mending depends on that particular crack, and its unique situation both within the context of my other works and within its original circumstance. Whereas I might attempt to symbolically mend a crack that extends the length of a room, other individuals will receive treatment indicative of their situation. The right form is just as important as the chosen method of alteration.

Part of my practice involves photography and video, which I believe have the capacity to become the visual manifestation of memory, space, and dreamscape. For this reason, many of these works are routed within myself. Although opening up to an anonymous audience is a delicate and therefore complicated process, I hope to create and present works in such a way that allows the personal to become ubiquitous.

What I hope to achieve with all of my work, is to engage the audience beyond the nature of object I create. For people to use my work as a jumping point for engaged looking and feeling. I strive for this in every media that I work with, whether it is a form of printmaking, video, drawing, or photography.

To take the unnoticed and push for it to become a part of the viewers consciousness.

Brenna Crabtree

When I begin making art, I cannot begin until I have a rule. The rule sets me on course. Last year I began with a basic formula: make small, banal objects bigger. I chose one object in particular, the plastic bread tag, and recreated it out of 1/4 inch plywood, 5ft by 5ft. To me the giant bread tag was about shape and colour, and giving power and presence to the little throw-away object that had inspired my project.

This semester I have made eight objects out of masonite that each loosely resemble a 2ft by 2ft bread-tag. These shapes were cut out with a scroll saw and I worked with the fact that at times the saw would stray from the lines I had drawn on the wood. I am pleased with the results because the objects are loose and ungainly, like 3-dimensional sketchbook drawings. I am interested in the combination of drawing and sculpture. I like to see how the works change when they lean against the wall or lie on the floor, and I am interested in how they touch each other and accentuate the negative spaces between them. I have adopted the bread tag as a device for experimentation, as an object whose shape is exciting to explore in different sizes and materials. It has persuaded to me to continue working with fluid, irregular shapes, like those conceived by blind contour drawings, in my sculptures.

Allison Crop Eared Wolf

My art comes from the core of who I am, and I am Niitsitapii, I am a mother, I am a wife, I am a woman, and I am an artist. It is from all of these places within me that my art is created.

When I decided that art was the direction I wanted my life to go in, I made a conscience decision to avoid what I labelled as “Indian Art”, without fully realizing and understanding the vastness of it. I didn’t want to be stereotyped or categorized into a certain type of art. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The raw feelings of displacement and feeling uncomfortable left me with two choice; follow the crowd, which led away from myself, or make my own path. The choice I made can be seen in my work. I began researching artists who happen to be First Nations from various tribes and what I discovered changed me.

My art practice began at a fundamental level, with my identity as a Blackfoot woman struggling to find my place within this world. I began with traditional concepts and through my own process modernized them. I produced a series of hand drums, entitled Skins, and then began the construction of a Blackfoot lodge or tipi, which was intended to be a self-portrait. The connection that was bridged between me and my culture through that process is one that I’ve never truly had. It was a intimate connection with my past. The construction of the drums and lodge was a combination of the traditional and the contemporary and my placement within these two worlds.

My current art practice revolves around the life and times of the modern “Indian”. From the humorous to the political and to the ever present stereotypical Indian, all of which are common and consistent elements within First Nations communities. I’ve investigated the strange phenomenon of Rez Dogz and have spent a lot of time with the infamous Indian Act, a document established in 1876 that is still being used today, established all “Indians” as wards of the state. I began by exploring the Indian Act in four works entitled The Unbounded, 2009, Indian Act: An Indian Perspective, 2010, Passport: Don’t Leave Home Without It, 2010, and 4350622001, 2010. All projects dealt with my personal response towards this document.

I then began exploring the response of other First Nations people within the Lethbridge area in a series entitled No Unauthorized Access, 2010. In this work I attempted to capture individual response of what the Indian status card as well as the Indian Act itself meant to them as First Nations people living today.

I feel that through my art practice and as an First Nations artist I have the opportunity and privilege to convey these ideas and concepts of my identity, memory, cultural knowledge, stereotypes, and the effects that colonialism has had on First Nation peoples. Art is a medium that allows me to express myself without compromise, it allows me to challenge those ideologies of the romanticized, dead, or drunken Indian. Within this challenging of stereotypes and politics I am able to reveal the real identities of First Nation people by creating dialogue, awareness and knowledge of our contemporary selves.

Kalen Hussey

Scars

This series is a closer look at the fascinating phenomena of skin mutilation, whether by accident or intent. These “passive” and “active” scars tell ambiguous stories when examined closely, without reference to their context. The figures become genderless and non-specific, and in this way the scars become the focus of the piece rather than the people.

Details of Gender

These images are intended to blur the lines between male and female, and force the viewer to question what makes one or the other, and more importantly if it really matters. With the understanding that the photograph of the face is of a man, one may begin to question the gender of the other figures represented, and find no clear answer.

The Shape of Things

This series is about mimicking silhouettes, and the relationship between object and subject. The work is about the process of becoming these objects chosen for their interesting shapes and the possibility of imitation, challenging me to perform a contorted dance in an attempt to duplicate what I see.

Chad Patterson

My work explores the visual and psychological experience of appropriated images and materials. I use various surface quality, technical approaches and subject matter to create interference and disruption in both that surface and the viewer. My works are arrived at by chance, cold calculation, or both and exist as an emotional response to the sensory cultural stimuli we all inject daily.

Bonnie Patton

In my practice I am focusing on ‘visual language’ and am trying to re-examine how we approach language. I like to play with both the meanings of words and the visual aspect of words. I like to try and figure out how language works and what I can do with it. I approach language as a game and as a place of transformation, and am also using language to look at or try to understand identity.

One way I have found to play with the meanings of words is to focus on particles of words and how they interact to change or produce meaning, such as in my prefix/suffix works such as preFIXation, which is a series or collection of language game pieces that include altered Rubik’s cubes, handmade Scrabble pieces, dice, and large-scale children’s blocks with common prefixes or suffixes on them instead of single letters or numbers. The game pieces can be scattered or rearranged to fabricate possible words made from different combinations of the prefixes and suffixes. I have also connected meaning to identity in works like Fragmented, Little Red No One and Ockham’s Razor, all of which feature either Ockham’s Razor (the philosophy rule in which the simplest [entity/idea] is usually the best one)and/or No One, Someone, and Anyone, the latter of which are presented as ambiguous entities.

I have also found a way to play with the visual aspect of words and language by studying and experimenting with typefaces and by playing with the format in which words can appear. This exploration is inspired by my own studies and by propaganda posters, general advertising, and visual or concrete poetry. Depending on the desired format, I may use a typewriter, the computer (Microsoft Word), or I might simply write/draw the work by hand. I also sometimes work with shapes related to text, such as lines made with text (Graphic Quality), or bars, which appear most often in my collages. My favourite materials to use for collages are discarded books from the campus library, cardboard, newsprint, and plywood. Except in painting, I tend to use natural colours in order to keep the visual focus on the materials and the shapes of the words.

Like Ed Ruscha, the phrases and words I use in my work can be found anywhere- they can be observations of shifts or relations between words (a way, away, anyway), song lyrics (the line in the It All Will Fall Right Into Place series came from the song “Gravity Rides Everything” by Modest Mouse), or quotes from conversations or memory (Buddha, Remain Calm…).

There are exceptions, but I find I work best in 2D media; I use found materials, collages, writing (handwritten or typed), photocopying, printmaking, and drawing to create my work, and I am looking to expand my work both in medium (by adding sound and vinyl letters) and in the scale in which the work is displayed.

Arianna Richardson

The obsessive collector creates from the cluttering objects that surround her. With techniques masquerading as decoration, hobby and craft, her aesthetics rooted in both in cheapness and decadence, whimsy and sadism, she fuses pieces of her collection together. Functions are thwarted and made absurd and uniqueness is gifted to the inherently impersonal and mass-produced objects.

Combinations of various articles in the collection occur organically and intuitively and are stimulated mainly through the act of collecting itself; it is often that the acquiring of an object is the catalyst for its fusion with something that was collected months, or even years, previous. Formal qualities, and their connotations and associations, stimulate the realization of these connections amongst the collection and the final piece is created.

The common aesthetic of decadence and cheapness is best attributed to the materials used: ribbon, glitter and tinsel speak of glamour and opulence while in reality, they are kitschy, cheap and excessively mass-produced. Their application is superfluous and made to be ridiculous, pointing towards this inherent cheapness. Allusions to violence are hidden among the adornments and appear only in the minute details. Sadism, subtle enough as to not confront the audience directly, is introduced as the function of the article is taken away; stunted. An invitation to recline on the “Tinsel Tick” is presented through the excessively floral pillows and ostentatious, glitzy surface while it can be seen upon closer inspection that the experience of it would be quite unpleasant: typified by pokes and scratches from the exposed, rusted wires. Similarly, the frills and ribbons used in “L’eau de Poodle” work both to hide and to draw attention to the impalement of the innocent figure upon the cheaply made lamp base.

The crafty and hobby-esque techniques found in each piece through various means of decoration help to root the practice in traditional ideas of the female role in the home. This role as woman as homemaker, in charge of choosing, personalizing and placing objects in the home, is perverted by the grotesque and bizarre appearances that each object assumes after its fusion. With each creation, she is simultaneously assuming and denying this stereotypical role: the objects themselves are non-threatening and acceptable, it is in the way that they are handled that her subversions become apparent.

Corinne Thiessen Hepher

I use the term Anarchaeologist to describe myself as a subversive collector, privileging matter that has been discarded and uncovering hidden thoughts and secrets. I collect ordinary objects and document them as signifiers of social culture. I transform found materials, exploring alternative meanings and narratives.

As a gleaner of visual and audio refuse, I create low-fi sound collages and video vignettes with a focus on everyday life. I collect by-products of feminine maintenance, especially artifacts that are used in maintaining “improvement”.

I explore the gleaning of culture in two ways:

1. by collecting, archiving, skimming, “hunting”, and gathering, I manipulate narratives and create false histories, reassembling objects in alternative ways to transform meaning and to re-create memory. I explore gleaning for survival and gleaning to repurpose materials. I ask the question, How do we transform ourselves (through performance/repurposing ourselves) to create new narratives?

2. by gleaning secrets, as a collector of secret obsessions and fixations. The parameters regarding normal and deviant behaviour changes over time. I find it curious that humanity can engage in romantic and social relationships with material objects, by assigning anthropomorphic qualities to them. I seek to dig up and uncover what is kept in secret and explore public and private life.

Through video, sculpture, performance and photography I explore distorted realities, false identities, and the carnivalesque. I am interested in exposing rigid social structures and challenging accepted hegemonies. Looking at accepted power discrepancies I expose how we participate and contribute to maintaining social order. I am interested in deviant behaviour and psychological issues pertaining to socialization in early life.

My recent work involves investigating play and dress-up from a psychological perspective, using costumes and body extensions to explore places of transition and transformation (creating mythological hybrid creatures). There is something I find valuable and appealing in what is rejected and discarded including people (“freaks”) who exist on the fringes. I am investigating areas where what’s humorous and/or disturbing intersect with cultural taboos in everyday life.

Jena Ursel

I have always been fascinated with textiles. Be it the feeling of a coarse scratchy weave between my fingers or the silky fibrous nature of hand spun yarn, the texture and colour of textiles sparks my creative mind. It was only natural that my artistic interests gravitated towards working with fabric, yarn and roving. As time went on, my work evolved from being focused around the properties of the materials itself to how I can manipulate them to express my moods and feelings. I suffer from mental illness, and much of the past has been consumed by feelings of grief, depression, anger, and euphoric mania.

For the past two years, I have taken medication on a daily basis. I had previously resisted pharmacological intervention, and had not reconciled with the fact that I may be on anti-depressants for life. Ironically, many of the symptoms of depression are identical to the side effects caused by anti-depressants. These symptoms include, but are not limited to nausea, apathy, mania, loss of appetite, hallucinations and thoughts of suicide. In Cause and (Side)effect (2009), I confront this paradox by displaying knitted words that have been created from the threads of second-hand sweaters. Each word is approximately body sized; they range in colour and texture from shiny hot pink to feathery black. The process of unravelling and repurposing the material echoes the rebuilding that often takes place when one recovers from depression.

My second piece from that period, The Button Project (2009) explores the daily routines that go along with depression. My goal for this work was to fabricate a visual representation of the medication I had taken to date. It consists of several rows of buttons strung on a line of crochet thread. Each row contains seven buttons and is representative of a weeks time. Each button varies in shape, size and colour, and hung together create a pattern like grid on the wall. They chronicle the daily ritual of taking medication.

When returning to the studio in January 2011 after having taking time off to complete my degree in Education, I quickly realized that in order to continue to be therapeutic and successful, my practice had to approach the topic of mental illness in a less literal way. My understanding of mental illness has grown, and through research and therapy I have learned to accept how my body functions. Recently, I have been experimenting with wet and needle felting. The repetitive nature of needle felting is enough distractions to pull my mind from the throes of dark emotion. I am able to combine colours and textures that emulate the body and represent how mine has been physically and mentally scarred. Felting has become my therapy.

Polyps I is the manifestation of the both the physicality and emotional nature of mental illness. Drafts of downy, cream and white roving have been needle felted into a light tan chiffon fabric. At first glance, Polyps I emits a strange feeling of calm despite its unorganized surface. Woven textures lead the viewers gaze about the piece, allowing them to wander in and out of fluffy crevices.

Perhaps unbeknownst to the viewer, each strand of roving has been violently pricked and barbed through its delicate under layer. Though seemingly unbroken, the chiffon has been scarred and disfigured. Upon further examination, the fabric hauntingly references the body. Lymph, blood and veins appear smeared across its canvas, and bulbous polyps interrupt any stillness once perceived by the viewer. Fragile and frightening, the marks are illustrative of the duality that is present both physically and emotionally within those who experience mental illness.

I intend to continue with the Polyps series, hoping to strengthen and refine ideas that express this duality.

About the Curator

Originally from Nova Scotia, Emily Falvey is now a Montreal-based independent curator and art critic. In 2009 the Canada Council for the Arts awarded her the Joan Yvonne Lowndes Award for critical and curatorial writing, and in 2006 she received the Curatorial Writing Award (Contemporary Essay) from the Ontario Association of Art Galleries. She is currently working on the manuscript for her first book of art criticism, titled Torn Halves and Half-Truths: Strategies of Paradox in Recent Canadian Art. Her curatorial work includes Exploded View (2010), Nite Ride (co-curated with Ryan Stec, 2009), Blue like an Orange (2009), and Buildup (2008). She was Curator of Contemporary Art at the Ottawa Art Gallery from 2004 to 2008.