Online Exhibition

earth blanket

October 5, 2021

The ULethbridge Art Gallery is pleased to present this new performance video by Lethbridge-based artist Kylie Fineday.

We commissioned the artwork as part of a mentorship in social practice with Alana Bartol, associated with her project Processes of Remediation: art, relationships, nature. The structure of the mentorship had to change drastically due to restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Creating the relationship between Fineday and Bartol took on added importance during the isolation and emotional pressure of lockdowns and lack of in-person contact.

With our gallery closed to the public, Fineday made the brilliant choice to create a private performance in which she explored materials and concepts and then documented this process to create a work for online audiences. Earth blanket is deeply personal, but the performance documentation also provides a powerful engagement with the social implications of land and a sense of home.

Josephine Mills

Artist Statement

I am a nehiyaw iskwew (Cree woman) residing in Southern Alberta, and while I often find myself longing for my home: my family and my reserve, it is a blessing to have access to this landscape. Through this work, I sought comfort from the landscape by making a blanket out of it.

When I was young, my grandmother taught me how to sew and how to bead, as she was taught by her mother. I carry these teachings and practice them in my own life and work. I’ve sought to expand upon these ways of working, incorporating them into my art practice.

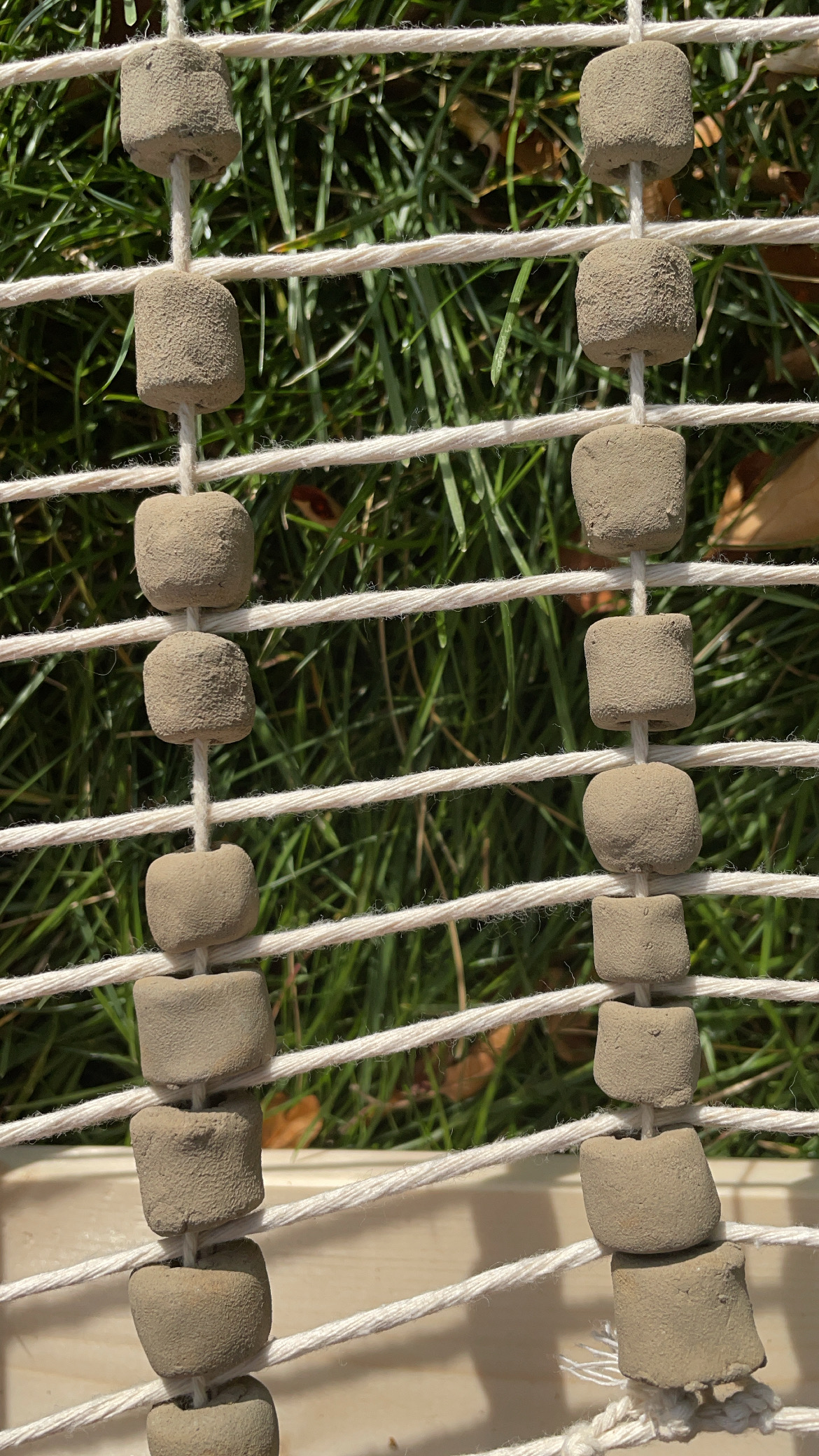

I made beads with clay that I foraged from the banks of the Old Man River. I crafted a large-scale bead loom with which to craft my blanket out of the beads. Beading on a loom was the first beadwork technique that my grandmother taught me. My grandfather made my sister and I each our own simple loom out of pieces of wood and nails. I recreated the same type of loom, but on a significantly larger scale, for the purpose of this project.

A blanket is not an object that would traditionally be made of beads or have beadwork, however I imagined the weight of the clay beads would offer some comfort, similar to a weighted blanket. I’ve often received comfort from mud, soil, dirt, clay, and sand. From childhood, playing in and with these materials, and even in adulthood, enjoying the textures and smells during moments of nostalgia. I feel a sense of intimacy with the earth when I fill my hands with it and feel it move between my fingers and against my body. Covering myself with the blanket of clay beads offers a nurturing and comforting sort of intimacy.

Knowing that the earth doesn’t belong to me or anyone, but I to it, I never planned to keep the beads beyond the completion of this work. I didn’t fire the clay, as I wanted to give back what I borrowed. Thanking the earth for sharing this comfort, and offering it back was always my intention.

Kylie Fineday

Making of Earth Blanket

This is video documentation of the process of making the blanket. From the gathering of the clay from the river bottom, to the sculpting of the beads, then the weaving of the beads into the loom.

Camera – Kristin Krein, Kylie Fineday

Plant Materials

This video depicts the gathering of some plants (dogbane), and then the extraction of the bast fibres from the dried stalks of the plants. This material ended up not going into the final blanket, as I quickly realized just how labour intensive the processing of it was going to be. It was a learning experience that came alongside the completion of this project.

Camera – Crystal Bauman, Kylie Fineday

Earth Blanket Photos

earth blanket Progress Photos

These photos depict still images taken during the process of making the blanket and working with the materials that went into (or were planned to go into) the completed project.

The Earth Holds Us

by Alana Bartol

Kylie Fineday’s Earth Blanket developed over the course of a mentorship as part of Processes of Remediation: art, relationships, nature, a project that began during the pandemic in the summer of 2020. For artists grounding their work in relationships with the natural world, a shift to virtual space can feel like upending embodied understandings of relationships to the land, history, culture, and other bodies.

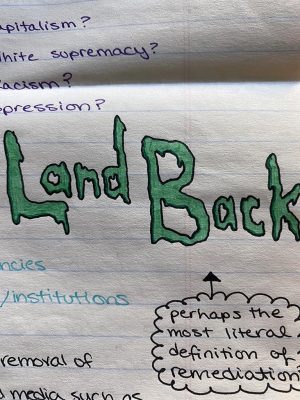

Finding somewhat steady ground through mailed correspondence, virtual and eventually in-person conversations, we shared definitions of and questions around remediation, reflecting on how we take up this concept in our artwork and everyday actions. What can be remediated, fixed, healed, cured? Capitalism, white supremacy, racism, climate change, pandemics, systemic oppression, language, concepts of care, knowledge, relationships, trauma, settler colonialism, land, contamination, resource extraction, toxic environments and cultures, academia, the arts – the list kept growing. As Kylie so aptly put, Land Back is perhaps the most literal definition of remediation.

Remediation refers to the action of remedying. In a time of climate crisis, during a global pandemic, every question and topic posed seemed overwhelming yet relevant and urgent. As conversations, relations, and ideas took shape, it was clear that remedies come in many forms. Processes of remediation require multiple strategies, approaches, and knowledges to apply remedies with responsibility, integrity, and care. Remedies call us into action, asking us to take up the work of remediation, restoration, and care in thorough ways.

From our first virtual studio visit, I was struck by the poignancy and potency of Fineday’s artworks. Growing up on Sweetgrass First Nation in Saskatchewan, Fineday moved to Lethbridge, Alberta to pursue a B.F.A., which she completed in 2020.

As a nêhiyaw iskwew (Cree woman) tackling Indigenous issues through art, Fineday’s identity and body are central to her work. Often rooted in performance, her interdisciplinary practice merges relationships with land, intergenerational knowledge and trauma, storytelling, cultural tradition, familial relationships, personal experiences, social justice, and activism. Fineday has developed an impressive body of work that confronts racist stereotypes and challenges settler-colonial systems, patriarchal social structures, and white supremacy.

Her thesis exhibition titled askîy iskwew, was a series of nude self-portraits drawn using natural charcoal and graphite. Exploring a desire to express herself as a sexual being, but outside of the power of the white colonial gaze, she blurs the images asserting corporeal sovereignty by “tak[ing] back power that has been taken from myself and women like me” (Fineday 3). As discussed by Nêhiyaw scholar Tracy Bear, corporeal sovereignty is the ability to make decisions about one’s body without colonial interference or oppression. Through her art, Fineday asserts her right to be visible, to resist erasure and dispossession, historical and present-day impacts of settler colonization.

The online exhibition of Earth Blanket offers generous insight into the artist’s process that weaves together learning from and of the land with intergenerational knowledge, culture, and resistance. For Fineday, beadwork is an act of remediation tied to healing, survival, and resisting colonial violence. “It’s a ritual, a ceremony. It is practicing my culture that is at risk of being lost…it is survivance” (K. Fineday, personal communication, summer 2020). Beading creates and sustains relationships across time and space through a connection to her grandmother, who taught her to bead.

Fineday brings together materials, processes, performance, and documentation to form an expansive and multi-dimensional artwork. Through video and photographs, we see the artist’s process of finding comfort with the land, evoking natural cycles of creation and destruction. Clay is gathered from the banks of the Old Man River and formed into individual beads, which are woven into a blanket on a large-scale loom. Each component of the work takes place outside, always in connection with the land, the artist’s body, and the elements. The sun shines and shadows of leaves dance across Fineday’s hands as they shape and pierce individual beads. To create the blanket, Fineday constructed the loom which was roughly her height. As beads are woven onto cotton string, the blanket takes shape. Ever-present throughout the process are the elements of wind, water, and earth, while the absence of fire allows the clay beads to be returned to the river.

Initially, all of the materials for the blanket were to be foraged and prepared by the artist. Though it was not included in the final blanket, documentation of gathering and extracting dogbane fibres is included in the exhibition. By presenting this learning as part of the process, special insight is shared. How often are artists so generous with their process? Fineday allows us to appreciate and observe learning new materials and methods. The audience is witness to the artist’s intention through an intimate relationship with land and learning with purpose, awareness, gratitude, and care.

Fineday also carries the name askîy iskwew, Earth Woman, given to her in ceremony. In the video entitled Earth Blanket, we feel as though we drift into the Oldman River Valley, an iconic landscape in Lethbridge, as early morning sunlight touches the tops of poplar trees. We see the artist enter wearing a white shift dress and pick up Earth Blanket from the land, already part of the landscape. While there are no signs of people in the landscape, it appears the viewer is a witness to a private performance as the artist lays on the ground covering herself with the earth blanket, seeking solace and connection with the earth.

The performance takes place in public at Indian Battle Park, a park that commemorates the site of the Battle of the Belly River (1870), the last major conflict between the Nêhiyawak (Cree) and the Siksikaitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy) in which the Nêhiyawak were defeated on the territory of the Niitsítapi (Blackfoot). A peace treaty was reached between the Nêhiyawak and the Blackfoot, but soon after the railway would reach the area that the Niitsítapi call Sikóóhkotok (Black Rock), known today as Lethbridge, and white settlers would exploit and colonize the land and its resources.

As the artist shifts positions, she lifts and re-adjusts the blanket on her body. How do the layers of history resonate with her at this site?

The name Indian Battle Park speaks to the need for reconciliation of the place name, of the history itself. When Indigenous histories are acknowledged, who writes the narrative, and who is it for? Canadian colonization includes the creation of parks. “Canada’s national parks system is predicated on Indigenous erasure and the myth of preserving a barren ‘wilderness’” (Little Light). Like the rest of so-called Canada, the creation and maintenance of parks was founded on Indigenous dispossession of land and colonial violence. As Little Light explains, through the eyes of the colonizers, Indigenous peoples were viewed as threats to the very land they lived on and cared for “despite the fact that we have had our own systems of ecological management since time immemorial. We have been and will continue to be an integral part of the landscape.” In this present-day park, Fineday asserts her right to be on and with the land. To feel safe, to rest, to connect, to seek comfort, even if it is only found for a moment.

As the performance moves from the land back to the river that the clay came from, Lethbridge’s High Level Bridge can be seen briefly in the background – but the focus is not recognizable colonial markers in the landscape. We are asked to re-orient ourselves, to the artist, the land, and the river as Fineday wades into the water, immersing the blanket and allowing the river to reclaim the beads.

Rooted in Indigenous ways of knowing, Earth Blanket resists singularity, ownership, and immortality. The natural materials are impermanent. The blanket can only be viewed through documentation. Only the artist, the land, and water hold the weight, textures, and transformation of Earth Blanket through physical encounter and in memory. Artist and author Jenny Odell writes, “Our idea of progress is so bound up with putting something new in the world that it can feel counterintuitive to equate progress with destruction, removal, and remediation” (191-192). Gifting the work back to the river frees it from ownership and honours reciprocity with the land. As the artist states, “Knowing that the earth doesn’t belong to me or anyone, but I to it, I never planned to keep the beads beyond the completion of this work.”

Earth Blanket is a reminder of connection and that we are earthbound, and that our fate is bound to the earth: we hold the earth, and the earth holds us.

Many thanks and gratitude to Kylie for making this work and participating in this mentorship. Thank you to Dr. Josephine Mills and the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery for this opportunity.

Work Cited

Bear, Tracy. Power in My Blood: Corporeal Sovereignty through the Praxis of an Indigenous Eroticanalysis. 2016. University of Alberta, PhD Thesis, https://doi.org/10.7939/R3348GS66. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

Fineday, Kylie. askîy iskwew. 2019. University of Lethbridge, BFA Thesis.

Little Light, Wacey. “We Are Still Here: National Parks, Colonial Dispossession, and Indigenous Resilience.” Remember/Resist/Redraw #20: National Parks, Colonial Dispossession, and Indigenous Resilience, Active History. 22 Jul 2019. https://activehistory.ca/2019/07/remember-resist-redraw-20-national-parks-colonial-dispossession-and-indigenous-resilience. Accessed 30 Oct 2021.

Odell, Jenny. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Melville House, 2019.

Tolton, Gord.“As-sinay-itomosarpi-akae-naskoy” – The Last Great Battle.” Ksiitsikominaa: The Thunder Chief Gallery, Fort Whoop-Up National Historic Site, Digital Museums Canada, 2013, https://www.communitystories.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=story_line&lg=English&fl=0&ex=00000821&sl=9283&pos=1. Accessed 8 Nov 2021.